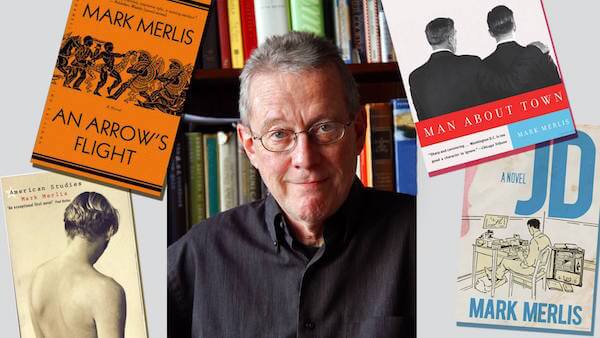

Author and novelist Christopher Bram. | COURTESY: CHRISTOPHER BRAM

The celebrated gay author Christopher Bram has written nine novels — including “Father of Frankenstein,” made into the film “Gods and Monsters,” which earned screenwriter Bill Condon an Oscar and stars Ian McKellen and Lynn Redgrave nominations — and two works of nonfiction, including 2012’s “Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America,” a literary history of the second half of the 20th century.

He and his partner of more than 30 years, the filmmaker Draper Shreeve, are longtime residents of Greenwich Village, where Bram recently sat down with Gay City News. The couple had a busy July, with Shreeve’s “Queer City” having tied for Best Documentary Feature at the qFLIX film festival in Philadelphia, and Bram’s publication of his newest nonfiction work, “The Art of History: Unlocking the Past in Fiction and Nonfiction.”

Christopher Bram talks about how and when gay stories can best be told

Kirkus Reviews said of “The Art of History,” published by Graywolf Press, “Though Bram teaches at NYU, there’s no hint of academic stuffiness in a book that offers the joy of reading as well as praising it.”

CHRISTOPHER MURRAY: You wrote a novel entitled “Almost History,” and now you’ve written “The Art of History.” What’s up with that?

CHRISTOPHER BRAM: I love history. I am a history nerd, I always have been. As a kid, I fell in love with history books long before I fell in love with fiction. I almost went to graduate school in history after I finished college, but found myself writing a novel instead. I forgot about grad school. But my second novel, “Hold Tight,” turned out to be an historical novel. I was delighted to discover I could combine my two great loves.

CM: “Hold Tight” is the one novel of yours that I have yet to read. It takes place during World War II?

CB: You’d love it. It’s about a sailor in a gay brothel in New York. One of the people I dedicated it to said, “But Chris, it’s your dirtiest novel!” I didn’t think it was that dirty.

CM: I remember reading your novel “Almost History,” which is set largely in the Philippines during the Marcos regime, and being astonished when I found out that you’d never even been to that country. The writing and the descriptions of place and atmosphere were so vivid and compelling.

CB: Well, I’ve never worked in a male brothel either! That’s one of the things I love about writing in the past: it frees my imagination to explore new experiences. In “Father of Frankenstein,” I was able to be a movie director in 1930s Hollywood. In “The Notorious Dr. August,” I could be a piano player who lives from the Civil War to the 1920s. I’ve always wanted to play the piano, but never could.

CM: At the very beginning of the new book, you say, “The truth of the matter is that many people — maybe the majority — don’t like the past very much.” Why do you say that?

CB: Well, because they don’t. The first chapter was originally going to be titled “Fear of History.” I regularly encounter people who don’t like to read history. All those strange names! All those foreign customs! And all those dates! It’s too much like math. For people like you and me, history gives us a whole new room to play in. But for many it’s unfamiliar and intimidating. They’re more comfortable in the present.

CM: In talking to you about history, it’s apparent that it is vividly alive for you. I have a friend who once got so mad at a character in “Nicholas Nickleby” that she threw the book across the room. Have you ever defenestrated any books? Who is a figure from history that you’ve really, really hated?

CB: I love books too much to throw them out of windows. Also our windows have screens. As for historical figures I hate? Napoleon. I don’t really hate him, but I don’t understand why anyone would hold him in high regard. He’s this bundle of energy but all he does is wage wars and invade different countries, which results in the deaths of millions. To take just one example: he sent an army to Haiti with orders to lie to their leader, Toussaint L’Ouverture, seize him, and re-enslave the Haitians. We’re supposed to admire this man? He was a basically a butcher. I feel similarly about Alexander the Great. He sometimes loved men, but he didn’t really love Man.

CM: Where would you take your time machine and who would you try to find?

CB: Elizabethan England to meet Shakespeare. I recently read or reread several books by James Shapiro, the Shakespeare scholar up at Columbia University, including his newest book, “The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606.” I loved his earlier book “Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?” Shapiro gets into the history of the absurd debate about somebody else writing Shakespeare, beginning with Francis Bacon and ending with the Earl of Oxford. He’s very good humored about it all. Along the way he paints a rich, wonderful picture of the Elizabethan and Jacobean theater world. London was basically a small town packed with very talented people, giants in fact. I’d love to see that world firsthand, even though I’d expose myself to the bubonic plague.

CM: In his play “The History Boys,” gay British playwright Alan Bennett has a character define history as “just one fucking thing after another.” What is gay history to you?

CB: Gay history is chiefly the actions of gay people. The tricky question is, what counts as a gay person? How gay do you have to be? A little bit of gay goes a long way… [Laughter.] I’m joking, but I’m serious, too. All it takes is a crush, a kiss, a romantic friendship, a shared bed. Much of that is so private it is almost invisible in history. There’s also the fear, the repression, the short bursts of persecution — luckily, they appear to happen mainly in short bursts. Only in the 20th century did this private life become so open it could be political.

CM: In “The Art of History,” you have some interesting things to say about written depictions of homosexuality

“Homosexuality is one area where fiction can complete what history, until recently, could only begin. The subject was taboo and the record sparse. But Mary Renault was able to flesh out — literally — the same-sex love of the ancient Greeks in such novels as “The Last of the Wine” and, gaudier and more exotic, “The Persian Boy.” Doris Grumbach took us inside the lives of the mysterious eighteenth-century ‘spinster’ couple known as the Ladies of Llangollen in her novel ‘The Ladies.’ There is a hypothetical what-if at the center of these books, an educated guessing at details, yet these men and women make more sense when their missing sexuality is included than when it was left blank.”

CB: It goes back to the old privacy of gay life. At its most basic, gay history is love stories, lots of private love stories. Fiction has always been much better at love stories than history is. Which is why fiction usually does a better job with gay experience. As gay life becomes more public, and more political, however, we see great nonfiction accounts. One of my favorites is “Coming Out Under Fire” by Allan Berube, about gay life during World War II. The institutional history there is about the anti-gay campaigns waged by the military. The real gay history is the many private love stories that endured. And then after the war, the first gay activist organizations begin to take shape.

The future writer as a Boy Scout. | COURTESY: CHRISTOPHER BRAM

CM: But we are clearly living through an epochal moment in gay history now. Such that it’s hard as an LGBT person living in New York City not to show up at the Stonewall after the Pulse nightclub massacre, not to be a living part of living history.

CB: You’re right. It’s been an amazing year. After the Supreme Court approved same-sex marriage, many people thought the battles over gay rights were over. It was old history now. We were no longer an issue, we were part of the mainstream. I never thought that myself, but I never dreamed a massacre in Florida could show not only how many friends we now have, but how many enemies are still out there. We gathered in protest and mourning at the Stonewall, where we had gathered in celebration five years earlier when New York State passed gay marriage. Meanwhile, it’s been grotesque how the Republicans interpret the concept of religious freedom as the freedom to discriminate against gays, especially those who want to get married. This year’s Republican platform is full of anti-gay and anti-trans planks. It’s so bad that even those delusional Pollyannas, the Log Cabin Republicans, are appalled. It’d be wonderful if gay struggles were all past history now, but the GOP keeps them alive.

CM: Your Gramma Mac and high school English teacher Mrs. Comstock are the benign hovering angels over “The Art of History.” You even have dedicated the book to your grandmother and in the first chapter you quote Jane Austen writing in “Northanger Abbey”:

“But history, real solemn history I cannot be interested in… The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars and pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all.”

CB: [Laughing.] I used the same Jane Austen quote as the epigraph for “Almost History.” The protagonist is a gay man in the State Department, but the second lead is his niece, who becomes an historian. It’s ironic that two women played the biggest role in opening my eyes to history. Because until recently history has been primarily a macho male domain. But they opened my eyes to a different kind of history. Maybe with more women involved, history will become less brutal. It won’t be perfect, but it’ll be more civil and less bloody. In a few months, unless we’re very unlucky, the United States will elect its first woman president. About time, too. I wonder what Jane and Mrs. Comstock and my grandmother would make of it.

THE ART OF HISTORY: UNLOCKING THE PAST IN FICTION AND NONFICTION | By Christopher Bram | Graywolf Press | $12 | 184 pages