Impresario is a word one doesn’t hear used too much in New York these days. It almost seems of an earlier epoch, when titans of the arts like Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins, and George Balanchine strode through the city with creative electricity flying from their fingertips. They were part of a very small circle — almost exclusively white and Jewish, mostly men — who may have lived ostensibly straight lives, but both loved and made love to other men (Balanchine an exception, with his well-known pursuit of young ballerinas). They came of age in the 1930s and ‘40s and defined the arts and culture of the their times.

“Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern,” the new art exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art, which runs through June 15, celebrates one of these lions for whom the word impresario isn’t expansive or encompassing enough. It does so through the lens of more than 300 works from the museum’s collection by a range of artists, Paul Cadmus, George Platt Lynes, and Pavel Tchelitchew prominent among them. The exhibit is at once a portrait of a protean and hugely influential arts figure in the 20th century, a mapping of the professional and social circles through which cultural influence surged, and a lens into the arc of fine and performing arts during the enormously exciting and active Modern period.

Kirstein, born in 1907 as the privileged son of an executive of Boston’s Filene’s Department Store, is perhaps best remembered as the co-founder with Balanchine of both the School of American Ballet and, in 1948, the New York City Ballet, for which he served as general director for more than four decades.

Starting out as one of the “Harvard lads” who stormed New York’s cultural scene before the start of World War II, Kirstein said of himself that he was “very happy to be brought up amid the relics and the legacy of the 19th century in England.” He has been called a polymath writer, art critic, and philanthropist, as well as a “fundraiser, troubleshooter, socialite tamer, and general advocate.” Most notably in terms of the current show, he was a collector who said of himself, “I have a live eye.” Nancy R. Reynolds, director of research at the George Balanchine Foundation, describes Kirstein as “the closest thing to a Renaissance man of culture that 20th century America has produced.”

Kirstein served during the war in a special unit charged with rescuing great works of European art from the Nazis, and, while on a art buying trip through South America for MoMA, Nelson Rockefeller, in addition to bankrolling the acquisitions, asked him to assess each country’s post-war loyalty to the United States. Kristen would go on to be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1984 and the National Medal of Arts a year later. He died in 1996 at 88.

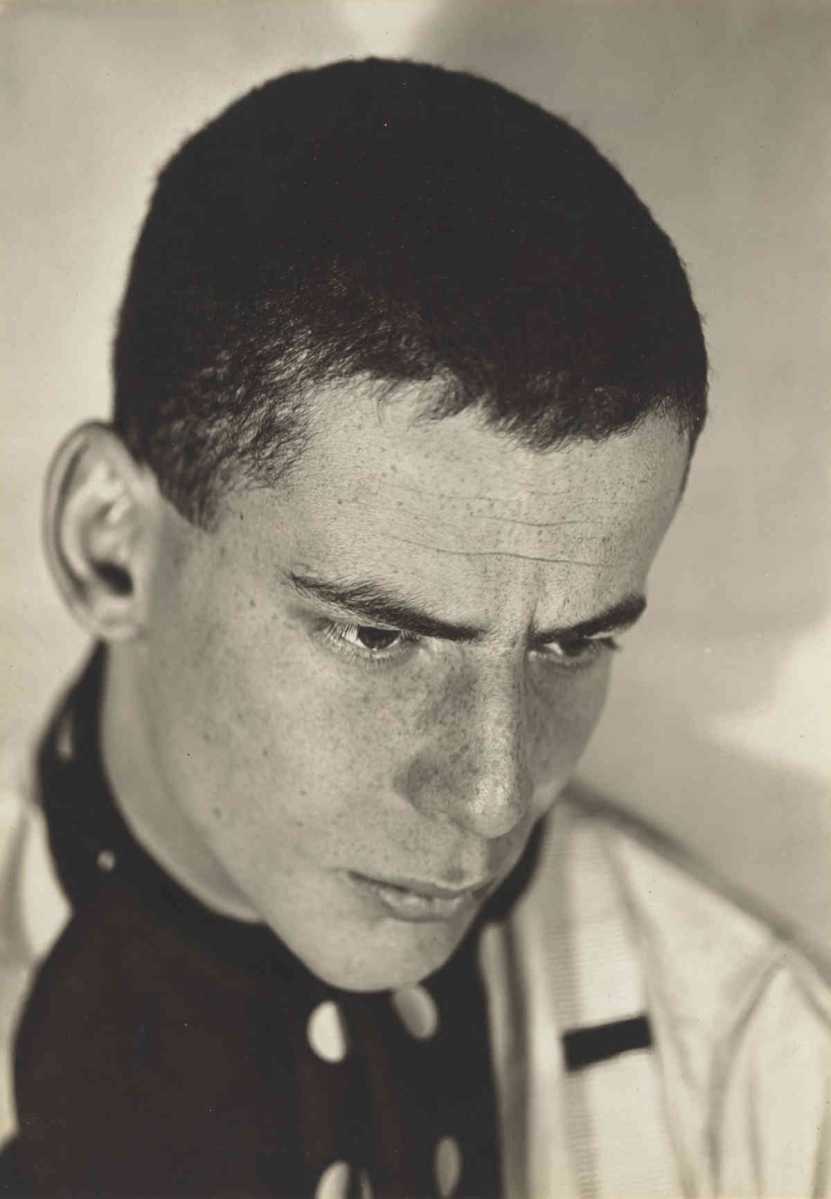

His life long championing of photography as an art form and of figurative work is well represented in the show, the first room of which introduces the man through portraits by Lynes, Walker Evans, and Lucian Freud. As one walks deeper into the exhibition, the iris widens. The works begin functioning almost as totems of Kirstein’s “over-lapping professional and social circles, largely queer” according MoMA senior curator Jodi Hauptman, who organized the exhibition with associate curator Samantha Friedman.

While it definitely seems like a show about a boy’s club, “Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern” is saved from a sexist parochialism by a generosity of spirit as well as the cross-cultural and boundless curiosity of a man who made no distinctions between art and friendship.

LINCOLN KIRSTEIN’S MODERN | Museum of Modern Art, 11 W. 53rd St. | Through Jun. 15: Daily, 10:30 a.m.-5:30 p.m. | Admission is $25; $14 for students; $18 for seniors at moma.org