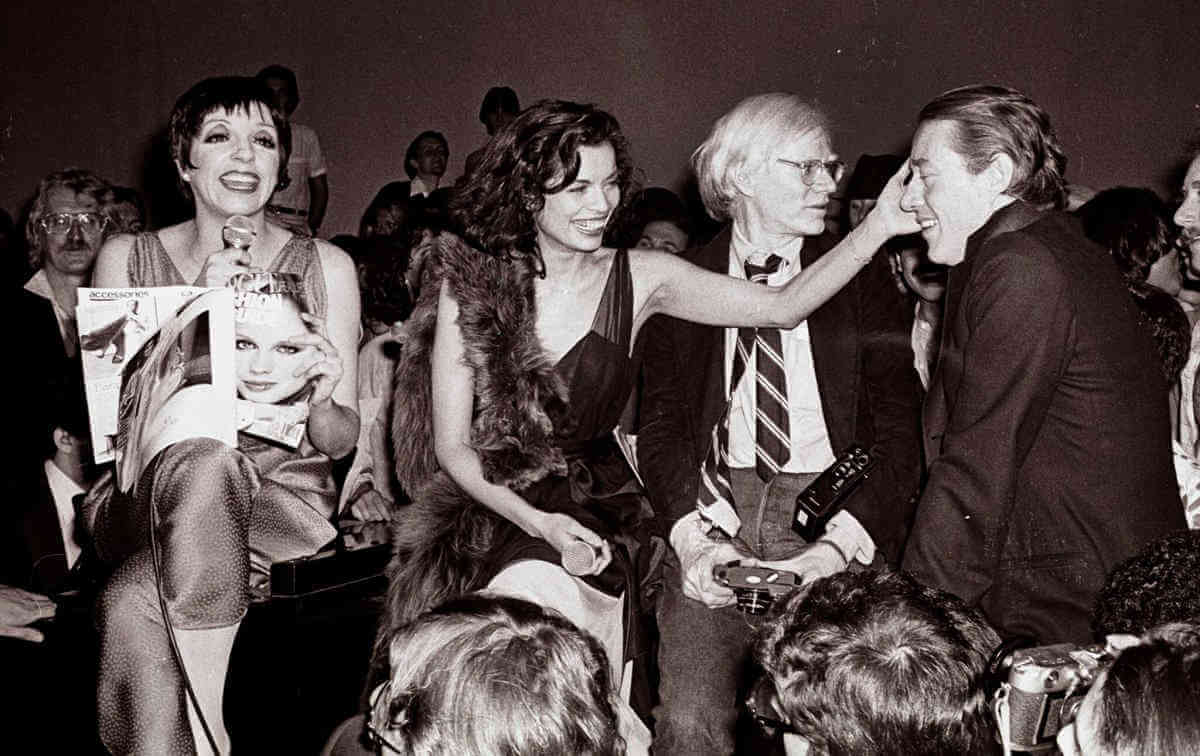

Matt Tyrnauer’s lively, entertaining documentary “Studio 54” takes viewers behind the velvet ropes and into the “experience” that was the famed New York City nightclub. Using hundreds of amazing photographs, as well as film clips, news footage, and interviews, Tyrnauer gets Ian Schrager — who co-owned the club with the late Steve Rubell and a silent partner named Jack Dushey — to “tell the story as it really happened,” nearly 40 years after its heyday.

The filmmaker chatted with Gay City News about his fabulous new doc.

GARY M. KRAMER: Did you ever get to attend the storied nightclub?

MATT TYRNAUER: No. I figured out I was in the third grade then — before my nightclubbing years.

KRAMER: The story is about this particular club, American culture in general, and filtered largely through Schrager’s memory. What decisions did you make regarding how to tell this story?

TYRNAUER: For me it was much more a story about the culture than it was about sex, drugs, and disco. They are appealing but don’t hold my interest as much as taking a look at a particular time and place where things of great consequence occurred. I see the 33 months of Studio 54 [in the original Schrager-Rubell-Dushey incarnation] coinciding with the Carter administration and it was the last volcanic moment of the sex revolution with the advent of birth control and the freedom and sexual expression and openness. Studio was the main venue for that freedom. And, of course, the story takes the darkest turn possible at the time the whole 54 shebang came tumbling down and Steve and Ian were sentenced to prison for tax evasion. And that was when the first unnamed cases of AIDS were reported.

KRAMER: You feature hundreds of photos and film clips. How much did you comb through and what was your criteria for inclusion?

TYRNAUER: We worked hard on finding images that really had never been seen before or weren’t the usual photos you’ve seen. We went through literally hundreds of thousands of images to select the couple hundred that made it into the film. We sought out archives of photographers who had never published their photos or we used alternate images, unseen contact sheets/ negatives that had never been printed. We were in basements of nieces or nephews of photographers. A great deal of attention went into identifying those photos. The 16mm footage of the club had never been seen before.

KRAMER: You interview mostly folks directly involved with the club. How did you select the different points of view — the employees, the patrons, the outside observers?

TYRNAUER: We don’t have celebrity voices, which was a conscious decision. The expected talking heads might have been the Rod Stewarts, Diana Rosses, George Hamiltons, and the paparazzi subjects. When I was shaping the film and conceiving it, that approach seemed less interesting to me because those people had a particular perspective and it was one that was pretty, I think, uninteresting in the end. The type of movie that dwells on interviews with aging stars and celebrities pulls you out of the documentary. You’re looking at this face and think they look great or terrible or they had work done, and I find that to be a distraction.

I made a calculated decision to focus on the real denizens of the club and who created the club and were the core constituency. The core wasn’t the pop music or movie stars, it was a certain class of New York persona, a creature of the night. It was only about 700 people who comprised this community of nightlife in New York. That was the world I wanted to capture and hear from.

KRAMER: There are a few discrepancies in club’s history that are debated, such as the story of the money in the ceiling. What do you want viewers to think?

TYRNAUER: I am a big fan of ambiguity, and I think that documentaries and feature films alike do a lot of handholding and I’m not all for that in every circumstance. In documentary, you’re seeing things from different perspectives, and I like to let that stand there and not over-explain.

KRAMER: “Studio 54” deals with a culture of celebrity, even suggesting that the nightclub inaugurated the age of celebrity. Why are you — and by extension we — so fascinated by celebrity?

TYRNAUER: I think 54 marked a kind of change in the way media packaged celebrities and it provided a new fishbowl for the changing media to exploit. It was a symbiotic thing. Ian and Steve saw this wave rising and they rode it for all it was worth. It’s really an exploration of this particular moment, which seems quaint in the age of Instagram celebrities. It was a new phenomenon. There have always been celebrities in one form or another, and Hollywood, in the studio era, changed the game. The 1970s, and the burgeoning media culture, and TV coming into own, and the simultaneous upward rise of the middle class increasingly seduced us. Our celebrity culture is a precursor of the Kardashians.

KRAMER: You focus on Schrager in interviews and Rubell through archival clips. What are your impressions of these two men, and how were they enhanced or changed over the course of your making “Studio 54?”

TYRNAUER: Steve was always an enigma to me. I knew people who knew him, and I met them when I was editor at large at Vanity Fair. It was interesting to discover him through the archival footage and through interviews with his friends and family. Steve was kind of a cypher to me. I wasn’t around. He had a cypher-like character in a way. He was a people person, and he was a little all-things-to-all-people — a pleaser, a mollifier, and a host. And there was some sexual ambiguity to his character.

I had Ian live on the hot seat, and I’ve known him for many years and what you see is what you get. He’s an intense and hardworking and very curious guy and a product of his place and class, lower middle class Jewish background like many of the smart people of that Brooklyn world who made the leap to mega-success. He has all the traits of those super-achievers of the meritocracy.

KRAMER: Would you call your film a cautionary tale about how Schrager and Rubell paid the price for their hubris? Do you think Studio 54 was ahead of its time, of its time, or a moment in time?

TYRNAUER: Nothing lasts forever. If they had not gone to prison, it would have faded away. The HIV/ AIDS crisis would have extinguished its star anyway and in the most terrible way. For me, the story is as much about New York as it is about the club. This was a disco version of Edith Wharton. It’s a tale of social mores of a city in the throes of change. It’s that moment of the old WASP establishment about to fall away completely, and there was now an open door for ambitious outer borough people to come in and take over the old society and reform it into what we know as the era of 54 and the resurgence of New York in the 1980s and onward. “Studio” is the origin story of that period. I see it as a fascinating piece of social history that is perhaps under-explored and getting at it through the portal of 54 seemed liked a good opportunity.

STUDIO 54 | Directed by Matt Tyrnauer | Zeitgeist Films in association with Kino Lorber | Opens Oct. 5 | IFC Center, 323 Sixth Ave. at W. Third St. | ifccenter.com