Long time executive editor, dean of NYC gay journalists, alleges “scandalous” actions

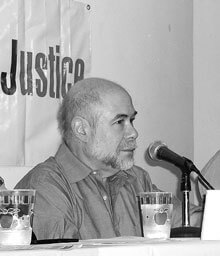

Richard Goldstein, an editor at the Village Voice since 1974 who was responsible for creating the newspaper’s first Queer Issue during gay pride week in 1979, has left the weekly newspaper effective August 2.

Goldstein, who was the newspaper’s executive editor—the number three editorial post—for more than a decade, is publicly clashing with Voice management about whether he was laid off or fired. And Goldstein’s comments, though carefully limited, suggest that legal action may be in the offing.

“I was fired. I was not laid off,” Goldstein said emphatically in a telephone interview on August 5.

“I have an attorney,” he added, explaining that he was curbing his public comments at the suggestion of counsel.

In an e-mail response to a request for comment the following day, Jessica Bellucci, a spokesperson for the Voice, wrote, “I… want to clarify that Richard was not fired, but laid off as part of a restructuring.”

Belluci’s e-mail went on to say, “Richard was laid off as the final step of a restructuring of the editorial department that began last month. It was not an easy decision. We are grateful for his contribution to the paper.”

In a New York Times story published August 9, Donald H. Forst, the Voice’s editor in chief, offered more specific comments about Goldstein’s departure, and Goldstein later that day expanded on his comments to Gay City News.

“The restructuring situation is tied into our efforts going from a weekly product to, with the Web, daily journalism electronically, in which we’re putting stuff up on a daily basis, sometimes on an hourly basis,” The Times quoted Forst as saying. “The restructuring is putting new resources there, to the Web site, while at the same time maintaining the paper.”

Forst also said, “I had two executive editors, and I only needed one,” adding that the executive editor who remained, Laura Conaway, “was more valuable, at this point, to me.”

Responding to The Times story, Goldstein shot back, “The comment made by Don Forst is not in keeping with the facts and I think the facts are scandalous.”

Goldstein refused to offer more specifics on his allegation, but he took pains to refute one implication of Forst’s comments—that his work may not be suited to the tastes of readers accessing the Voice online.

“My pieces also do very well on the Web, frequently among the top ten in terms of hits,” Goldstein said. “From the action on our Website and the response I get when I lecture, I know I have appeal among young readers… If the question is my usefulness to the paper, if they are Web-centric, [the suggestion that I am not useful] is not true.”

Goldstein, who declined to give his age, acknowledged that younger readers and writers often use words and even sentence syntax in new and innovative ways, but insisted that the ability to communicate in ways that specifically appeal to such an audience, when appropriate, was not tied to a writer’s age. He also suggested that whatever criteria the Voice is using in its recent employment decisions, quality was not at the top of the list.

“I wonder about the paper’s ability to attract young and vital readers if it gets rid of its creative writers and editors,” he said.

Goldstein argued that his firing was unrelated to the restructuring Forst and Bellucci mentioned. Sources familiar with the operation of the Voice agree that the editorial staff was trimmed by six in early July, to a size that Forst, in The Times, estimated at between 60 and 65. The layoffs included Thulani Davis, an African-American journalist who was a senior editor and drama writer, and Alisa Solomon, a lesbian who writes about politics, gender and the arts, has long been associated with CUNY’s Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies, and teaches business journalism to graduate students at Baruch College.

Observers agree that, separate from the restructuring, the newspaper also replaced Matt Haber, who had managed the Web product for the past five months, and that Cynthia Cotts, who wrote Press Clips, a media watch column, recently resigned.

Solomon’s account of her layoff supports Goldstein’s contention that the restructuring took place well in advance of his firing. In a telephone interview, Solomon said she was given notice in late June about three weeks ahead of her July 9 end date.

“I was absolutely blind-sided by my layoff,” she said. “I didn’t see it coming.”

Solomon had written for the Voice since 1983 and was a staff writer for the past 14. Last year, Solomon wrote a series of articles about immigration, for which the Voice nominated her for a Pulitzer Prize. As a staff writer, she was paid an annual stipend plus a page rate for those stories published. Sources familiar with Voice operations say that staff writers hired more recently are paid straight salary, presumably ensuring more predictable expenses and greater flexibility in responding to the demand for copy on the Web.

For Solomon and others at the Voice, as well as journalists who have done freelance work for the newspaper in the past, however, too great a demand for copy was not the problem. Instead, it was the shrinking space for editorial content in the Voice’s print edition. The tough economy and shrinking ad pages, experienced everywhere in the media in the past several years, have certainly been key factors, but observers also point to page competition from types of content unknown in the iconoclastic Village Voice of old—sports pages, sex columns tripping over each and what those in the business call “service journalism,” but readers are more likely to think of as lifestyle helpers.

Solomon, who said she will be doing regular theater writing for the newspaper on a freelance basis and was invited to pitch political stories as well, seems to have taken the shrinking opportunities to get published while on staff in stride.

“As anyone can see, the feature well is shrinking,” she said. “It was harder to get stories approved. But I have done plenty of writing recently. Like anybody, I have had frustrations about space.”

Solomon dismissed the suggestion that the changes going on at the Voice represent a stark repudiation of its historical mission.

“For all my 21 years at the Voice, I don’t remember a time when people didn’t say, ‘I used to read the Voice. The Voice is going downhill,’ referring to some supposed earlier golden age at the Voice,” she said. “I simply wasn’t happy that pieces got shorter.”

Despite the departure of Goldstein and Solomon, there is no indication that the Voice is reducing its commitment to gay and lesbian content or staff. Conaway, the surviving executive editor, recently wrote an essay entitled, “Dear Mitt: One Queer’s Message to the Massachusetts Governor,” about the politics of same-sex marriage.

Solomon may be looking forward to a continued professional association with the newspaper, but she was willing to speak out against Goldstein’s firing.

“Losing Richard is enormous and tragic,” she said. “I think it is just absurd.”

A year ago, while she was still writing the newspaper’s Press Clips column, Cynthia Cotts demonstrated even greater willingness to take on the Voice. In the wake of the layoffs of six editorial staff members last July, Cotts, in her column, wrote, “Sadness and paranoia now rule, and a rumor is circulating that more cuts will follow.” Her column took note of the fact that 85 of the 115 members of UAW Local 2110 who worked at the newspaper signed a letter declaring “our profound outrage and disgust,” and stating, “We believe the motive here is greed on the part of the paper’s owners, a greed that is apparently willing to sacrifice editorial quality in pursuit of profits.”

Profits and paranoia are still in the air in any discussion of what’s going on at the Voice. The Times reported that Voice publisher Judy Miszner conceded that advertising revenues “could be better,” even as Forst insisted that the newspaper is profitable and not up for sale. Meanwhile, among those close to the Voice, a rumor has been circulating that Local 2110 has filed charges with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) alleging that the newspaper is pushing a “speed up” of work among salaried staff members responsible for writing copy for the Website. Local 2110 did not return a call seeking comment, but the NLRB regional office in Manhattan said no charges have been filed against the newspaper.

For his part, Goldstein is not commenting on any of these matters, at least for the time being. But, in an interview, he was willing to recall his long history with the Voice that began in 1966 just after he got his masters in journalism from Columbia University and showed up at the newspaper’s offices, then located in Sheridan Square, saying he wanted to be a rock critic.

In the years that followed, he became close to rockers Jim Morrison and Janice Joplin, and in the 80s was among the first to write about artists Keith Haring and David Wojnarowicz. After spending three years at New York magazine in the early 70s, he returned to the newspaper as a senior editor in 1974 at the time that Clay Felker, whom he met at New York, bought the Voice. Goldstein first came out in the late 70s when he had what he described as a “a torrid affair” with the newspaper’s art director. Within the same year, he produced the Voice’s first Queer Issue, which he has stewarded every year since. Goldstein counts as one of his proudest achievements his mentoring of Mark Schoofs, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his 1999 series on AIDS in Africa published in the Voice.

Perhaps Goldstein’s most poignant memory, however, is schlepping across the Bronx as a high school student to one of the handful of places in the borough that carried the Voice. Even after getting his B.A. at Hunter College and studying journalism at Columbia, the newspaper’s allure had not worn off and he went straight from graduate school to the Voice.

“It was a dream come true,” Goldstein recalled. “But they paid bupkis. Columbia was horrified and said I brought down the earnings curve of my class.”