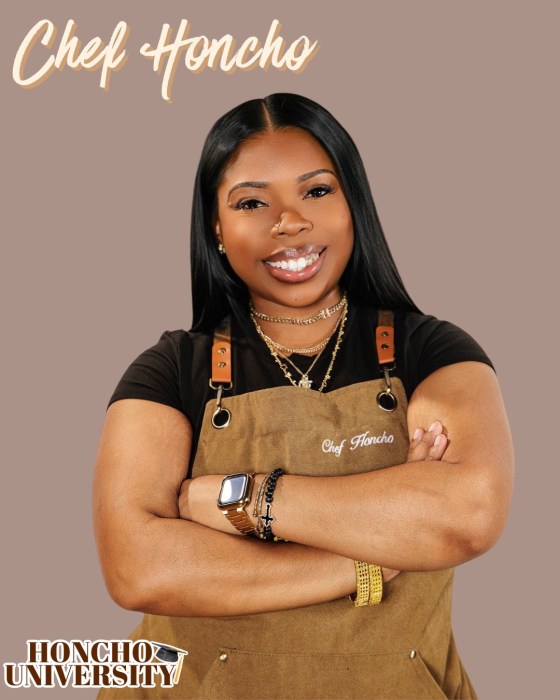

Christine Goerke, Ildikó Komlósi, and Anne Schwanewilms in Richard Strauss's “Die Frau ohne Schatten.” | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

BY DAVID SHENGOLD | October 24 proved a happy night at the Metropolitan Opera: a performance of Bellini’s mighty “Norma” in which all four leads belonged on the great stage. How often does that happen in major “red sauce” Italian operas these days? The John Copley/ John Conklin production remains an eyesore, with incredibly gauche, senseless use made of the heroine’s children, exhibited to the whole Druid clan just when she’s trying to protect them from exposure. This moment — potentially among the most moving in opera also featured one of many peculiar translations, rendering Norma’s plea to her father — “Pensa che son tuo sangue” (“Remember, they are your blood kin”) — as “Remember, I am your daughter”.

But the singing, particularly that of the terrifically gifted, rich-voiced, and expressive Jamie Barton in her first major Met role as Adalgisa, triumphed over the staging and Riccardo Frizza’s superficial, sometimes rushed conducting. Barton phrased her words and music as if experiencing them afresh — something not true of Angela Meade’s Norma, though much of the marathon role was truly remarkably well vocalized.

Meade has steadily improved her Norma from its Caramoor to Washington showings, and while she manages most of the hurdles straightforwardly she occasionally sharped or took refuge in pianissimi. At best she channeled anger and earnestness; but the large tragic arc of the character eluded her, and one felt duly impressed rather than moved.

Monteverdi through Richard Strauss featured at Carnegie, Lincoln Center, the Met

Past his opening aria, Aleksandrs Antonenko sang with increasing warmth, relative agility, and dynamic shading. He was one of the Met’s better recent Polliones. Ievgen Orlov debuted as Oroveso with a big, buzzy Christoff-like bass, not exceptionally elegant but sturdy and powerful. Why isn’t he singing Gremin in “Eugene Onegin”?

November 7 showed the Met functioning at its best with the welcome revival of “Die Frau ohne Schatten” in the late Herbert Wernicke’s brilliant production. What a “Ring” he might have given us! Vladimir Jurowski, back in the pit, opened all the cuts imposed last time and led a fantastic performance, which should only improve. The breakout news was the fabulous singing and heartfelt acting of the Dyer’s Wife — the trickiest part in the opera — by Christine Goerke, now at full peak sounding as what many of us thought she’d always be: the Great American Dramatic Soprano of her time. The audience roared approval.

Anne Schwanewilms made a welcome debut, her slightly “tubular,” lightish sound making for a restrained but stylish, thoughtful Empress; opposite her, tenor Torsten Kerl was rather wooden but sang pleasingly enough. Johan Reuter, extremely sympathetic onstage and lovely at quieter moments, really needed more weight of voice for the Dyer; what there was, was choice. Ildikó Komlósi (Nurse) moved and acted well but her tone — and her German diction — came and went. Still, all were well within the frame of this weird, wonderful fairy-tale opera, a mind-blowing experience.

The Philharmonic, on November 9, played a pleasant but curiously unbalanced program of vocal music under Bernard Labadie. The first part brought Bach’s cantata “Jauchzet Gott,” with Matthew Muckey’s fine trumpet and Miah Persson singing with style and generally bright tone, though Labadie’s swift tempi sometimes cost her loss of pitch and tone at line endings. One aria (“Let the Bright Seraphim”) from Handel’s “Samson” followed — why not one for each of the trio of soloists who joined Persson and considerably larger forces for the Mozart “Requiem,” as completed by Robert Levin, after intermission? Stephanie Blythe sounded duly luscious and Québecois Frédéric Antoun reaffirmed his beautiful timbre and stylistic command — a tenor sorely needed in Mozart and light French roles at the Met. Joseph Flummerfelt’s New York Choral Artists performed remarkably.

November 13 brought the US premiere of the great Kunstdiva Anna Caterina Antonacci’s solo project “Era la notte” to the Rose Theater. Wonderful as it was to see this nonpareil artist (rarely in New York) and hear her incisive declamation in four beautiful laments by Monteverdi, Barbara Strozzi, and Pietro Antonio Giramo, I found the evening rather disappointing.

Increasingly, BAM and — here, for its shakily defined” White Lights Festival,” which comes wrapped in positivist New Age rhetoric — Lincoln Center seem prone to import “snob hit” events created for a festival circuit seemingly linked by the primacy given to images suitable for brochures or website viewing. We had a striking wall of candles here, plus the branding of Christian Lacroix costuming, but the composition had the non-organic, commodified feel of one of those Starbucks compilation CDs of world music.

The musicians from Les Siècles were not overly impressive, not on the (very high) level of the music or Antonacci herself. Solo shows are hard; real bêtes de théâtre are best experienced in interplay with others. But this brief encounter with Antonacci’s art left one wanting more of substance, soon.

Carnegie’s Zankel Hall hosted a better baroque ensemble, Jonathan Cohen’s Arcangelo, on November 18. Violinist Alina Ibragimova shone tonally and stylistically as soloist in J.S. Bach’s “A Minor Concerto.” She then joined her eloquent playing to Katherine Watson’s singing of the harmonically entrancing aria “Mein Freund ist mein” from a cantata by Bach’s paternal cousin Johann Christoph (1642-1703). Like the great Christine Brandes, Watson manages to inscribe a dark coloration on a texturally light, pure lyric sound. For a baroque soprano, she could make uncommonly effective use of her lower range.

After intermission, Russian baritone Nikolay Borchev joined Watson for Handel’s sparkling duologue “Apollo e Dafne.” The brief mythic tale was tricked out with a bow and arrow as props, but they didn’t distract. Watson was again very impressive in sustained as well as trippingly agile passages. Borchev, a little empty at the very bottom, showed good coloratura, a fluent timbre, and a properly self-regarding affect as Apollo.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.