Thirty years ago, lesbians weren’t hip; they weren’t even on Americans’ radar. If they were mentioned at all, the comments were unflattering and filled with vitriol.

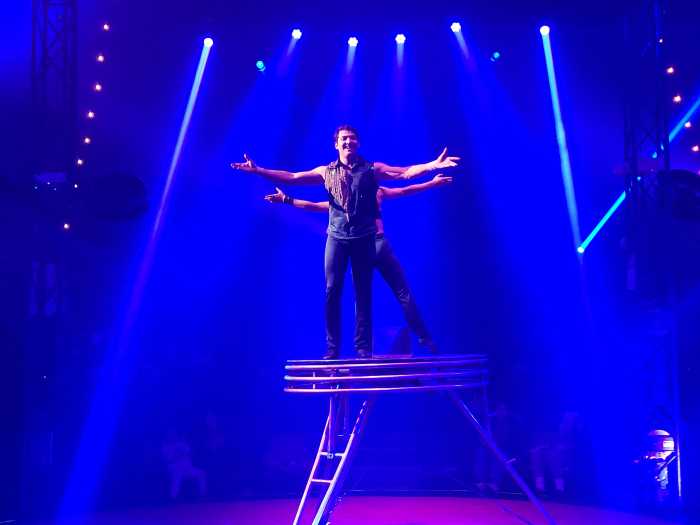

Tired of the lack of visibility, six of New York City’s lesbian activists came together with six other queer women activists in 1992 to form the Lesbian Avengers. They were edgy. They were unapologetic. They were fierce. They were in America’s face and breathing fire, literally, after a lesbian circus performer taught the activists how to eat fire to protest a firebombing. Their mantra became “The fire will not consume us, we will take it and make it our own.”

At a time when the feminist movement was under attack and the LGBTQ community faced fierce adversity against the backdrop of the HIV/AIDS crisis, the Lesbian Avengers struck a nerve and ignited a revolution in lesbian activism.

The core members of the group included New York City lesbian activists Anne-christine d’Adesky, Marie Honan, Anne Maguire, Sarah Schulman, Ana Simo, and Maxine Wolfe. They joined forces to design a branded grassroots direct action movement for a lesbian feminist response to the issues of the day.

The timing — 1992 — was right.

“Lesbians clearly wanted something like this,” Maguire said, noting the Lesbian Avengers wouldn’t have spread “if the need was not there and lesbians were not ready for something like this.”

“[The Lesbian Avengers] was seen as very feisty, very cool, very sexy, and kind of fierce,” she continued. “I think a lot of lesbians were waiting and were ready when the Avengers started.”

D’Adesky, speaking about the generation of young queer women who were proud of their feminist and lesbian identities, said “we were ready to bring women together and see what it was that they wanted… there was a real sense of fun in it.”

Gay City News spoke with some of the founding members of the Lesbian Avengers to reflect on the movement’s legacy and connect the dots to today’s world 25 years after the last chapters dissolved.

The founding of Lesbian Avengers came from the women’s rights, reproductive rights, ACT UP, and anti-nuclear movements of the 1970s and 1980s. They were also journalists, filmmakers, and other creatives who were media savvy.

Schulman described the founders of the Lesbian Avengers as “very politically sophisticated people” who made deliberate, purposeful decisions to create a movement using “modern aesthetics” that played off right-wing fears and pop culture to attract younger, diverse activists.

Their goal was to attract and harness the energy of the new generation of activists and train them in grassroots activism for lesbian visibility and LGBTQ rights. Nearly 100 queer women showed up at the first meeting during New York City Pride weekend.

The Lesbian Avengers fought against the Christian right’s anti-Rainbow Curriculum, which took children’s books like “Heather Has Two Mommies” out of school classrooms and libraries. In 1991, the New York City Department of Education’s Children of the Rainbow Curriculum — intended to foster diversity and inclusion in schools — faced aggressive opposition.

The Lesbian Avengers called out hate crimes against the LGBTQ community by protesting the firebombing of a house in Oregon’s capital, Salem, where a gay man, Brian Mock, and a lesbian, Hattie Mae Cohen, were burned to death. They protested and helped other lesbian communities in the United States demonstrate against state lawmakers legislating hate in their respective states, like Colorado, Idaho, and Maine.

The most enduring legacy of the Lesbian Avengers is the Dyke March. The first march was orchestrated by the Lesbian Avengers along with lesbian groups from Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and other cities on the eve of the LGBTQ March on Washington in the nation’s capital in 1993. An estimated 20,000 queer women descended upon Dupont Circle and marched to the White House for the first time April 24, 1993.

The action caught fire with lesbians. Dyke Marches immediately popped up in San Francisco, New York City, and Atlanta ahead of those cities’ respective pride parades in 1993. Today, San Francisco and New York City host the largest Dyke Marches and hundreds more marches happen around the world on the eve of annual pride parades.

“That is one of the legacies of the Lesbian Avengers,” Maguire said. “The Dyke March is one of the most popular events in New York City.”

Schulman, who wrote the Lesbian Avengers Handbook, said developing lesbian feminist organizing and leaders was another important aspect of the Lesbian Avengers.

“I think for a period it really gave people a place to evolve and that’s really great,” she said. The Lesbian Avengers, she said, demonstrated that “regular people can change the world and you can start organizations without any money.”

D’Adesky agreed, adding that she sees the influence of the Lesbian Avengers everywhere 31 years later.

“I see them in places all the way up to [the] State Department,” she said. “There are people who created tons and tons of institutions and more importantly as being members of so many different political movements.”

The Lesbian Avengers grew to upward of 400 queer women in 60 chapters throughout North America and Europe at its height, said Marlene Colburn, who managed the Lesbian Avengers’ contacts during its operation. The New York chapter ended around 1995, according to award-winning journalist and longtime Gay City News contributor Kelly Cogswell, whose partner is Simo, a founding member. Cogswell was also very active in the Lesbian Avengers and wrote a memoir about her years with the group, “Eating Fire: My Life as a Lesbian Avenger.” Cogswell said San Francisco was the last holdout where activities ended around 1997.

More than three decades later, the LGBTQ community finds itself under a vicious assault, with state lawmakers legislating hate with hundreds of anti-LGBTQ laws across the country, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. At least 150 of the proposed laws target transgender people, according to the Human Rights Campaign.

Founding members of the Lesbian Avengers remember the dark days of the 1990s, but they all agreed that the new generation of activists need something different than the Lesbian Avengers to respond to today’s challenges. It’s become more dangerous than during the Lesbian Avengers era, they said.

“Then we had construction workers, maybe cops who didn’t like you,” said Colburn. “Now you’ve got the Proud Boys bringing guns to the party. That’s not what people want to face.”