When Ntozake Shange’s “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/ When the Rainbow is Enuf” arrived at the Booth Theatre in 1976, it was a revelation. The interconnected series of 20 monologues and dances gave voice to a group of black women. Shange called her piece a “choreopoem,” and the intermixing of lyricism and hard-edged honesty was joyful, eye-opening, and harrowing all at once. The piece also had the distinction of being only the second play by a black woman to get to Broadway — after Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun” in 1959.

The piece is back at the Public Theater, and it is still as exhilarating and profound as it always was. Perhaps given the current environment it is even more timely. It’s a reminder that simple words, movement, and authenticity can make truly exciting theater.

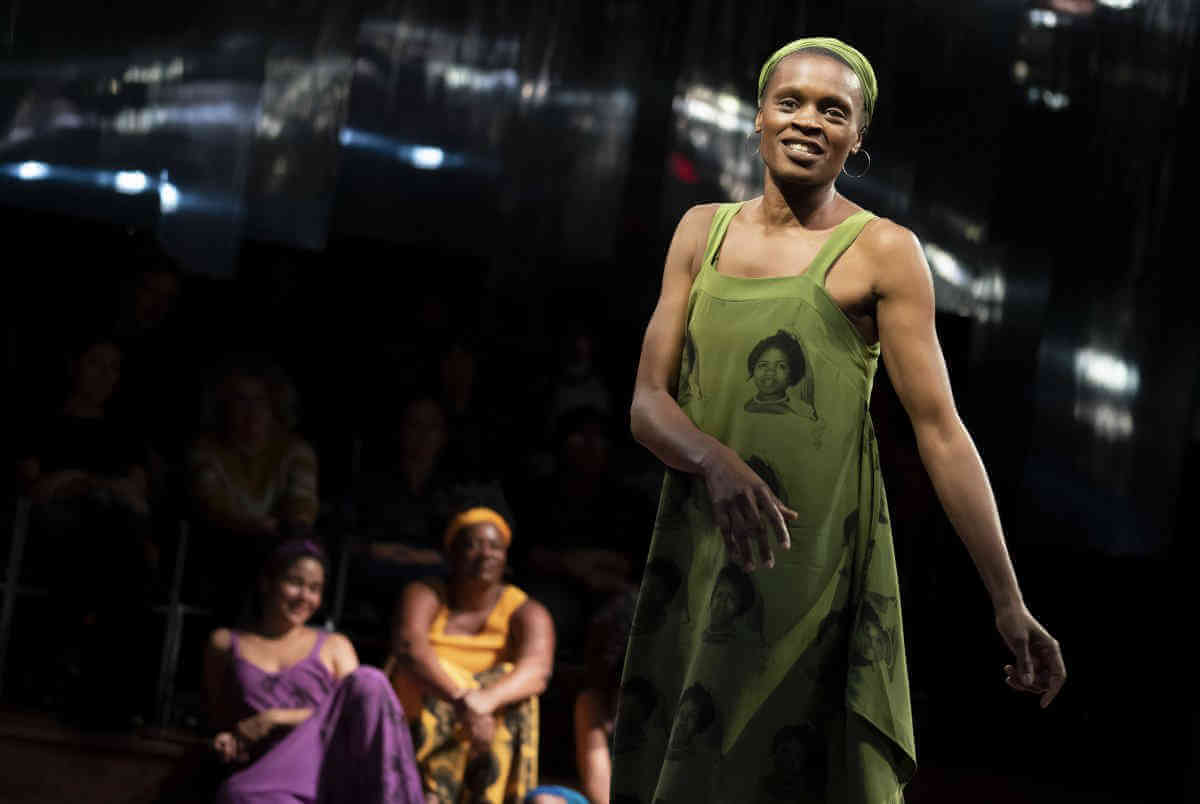

The poems talk with artful frankness about identity, abortion, bad relationships, and the challenges of being a black woman in this world. Watching and, most importantly, listening, one is alternately cheering and crying — and always feeling. Under the direction of Leah C. Gardner with choreography by Camille A. Brown, the piece sweeps the audience into the lives of these women in a way that is both highly presentational and remarkably intimate.

The women are identified only by a color, as in The Lady in Green, Blue, etc. The company is extraordinary, including Celia Chevalier, Danaya Esperanza, Jayme Lawson, Adrienne C. Moore, Okwui Okpokwasili Alexandria Wails, and, at the performance I saw, D. Woods. Together they form a fluid ensemble that is ever present even when others have center stage. They are there for each other. You should be there for the artistry and gorgeously moving theatricality.

What’s art got to do with it? That’s the question that hangs in the air throughout “Tina: The Tina Turner Musical.” Turner is one of the most electric, exciting rock goddesses to ever hit the stage. It’s a story of grit, survival, and unique talent that has all the components of exciting theater. And then there are the songs. If those don’t have you dancing in your seat, it’s hard to imagine what will.

Unfortunately, what’s on stage at the Lunt-Fontanne is a bland, predictable jukebox musical that’s a literal chronology of Tina’s life while offering no insights into the character. Tina’s story is well known, from a 1993 biopic and countless tabloid stories. Born Anna Mae Bullock, she caught the eye of Ike Turner who made her a star, named her Tina, married her, abused her, and drove her away. Devastated, she recreated herself and went on to become a bigger star than ever. If there were ever an opportunity to explore the internal life of an artist and what drove her to succeed (other than needing to pay the mortgage), this would be it. The book, though, by Katori Hall with Frank Ketelaar and Kees Prins, never looks below the surface of the woman.

As with many jukebox musicals, the songs often feel forced into the narrative. Why, for example, has “Private Dancer,” a song about a sex worker, been put in the context of dealing with hard times? On the positive side, though, “I Can’t Stand the Rain” makes more sense in that context.

Phyllida Lloyd’s direction is mechanical but ploddingly capable until Tina gets a chance to cut loose. The effort would have been more entertaining if it had been crafted as a tribute concert showcasing the songs. That’s what the last 20 minutes are anyway, and it’s then that the show becomes exciting. Adrienne Warren as Tina is a dynamo. She’s got the wigs, the iconic outfits, and the pipes to channel Tina, and she does so beautifully. Still, ending with an amped up concert doesn’t excuse what has gone before.

As with many of these undertakings, the company outshines the material. Daniel J. Watts, in particularly, is marvelously mercurial as Ike, the most well-developed character in the piece. Mark Thompson’s sets and especially costumes are evocative, and Bruno Poet’s lighting design is generally excellent. The sound design by Nevin Steinberg is frequently muddy in the book scenes, but bright and dynamic in the concert scenes.

This is undemanding and familiar, so that may be its edge in marketing a Broadway show. For tourists or die-hard Tina fans, it may be worthwhile. But if you love what’s new and interesting in the theater, you problem don’t need this jukebox.

Within weeks of its first publication in 1843, Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” was being knocked off with pirated versions selling for a penny a copy and had already been adapted for the stage by other writers. Dickens railed against unscrupulous “vagabonds and thieves” — he ultimately won a costly and emotionally draining lawsuit against Parley’s Illuminated Library to stop the production of “A Christmas Ghost Story” — but he gained nothing from it, given the virtually non-existent copyright laws of the time. The vulgarization and trivializing of his work, to say nothing of the lost revenue, haunted him for the rest of his life.

In the nearly two centuries since, the “Carol,” of course, has seen innumerable permutations from movies to musicals, Muppets, and Mr. Magoo. Still, Dickens would surely have counted among the biggest “vagabonds” Jack Thorne for his ghastly, ghostly 2019 adaptation.

It’s not that Dickens’ text is sacrosanct but what is especially appalling about this version is the erasure of the social context that gave Dickens’ story its power. In the original, the unreformed Scrooge represents the unfeeling world that cares little for the poor and would happily relegate them to workhouses or treadmills. Surely it would not take much to contemporize the tale given today’s political climate. But rather than address pervasive selfishness and greed, Thorne has invented an “origin story” for Scrooge, casting him as a man who became a monster because his father didn’t love him, reducing the great ethical lesson of the tale to neurosis. Dickens’ Scrooge is awakened to the error of his ways by revisiting the past, seeing for the first time the present as it is, and, his heart touched, understanding that he can change the future. In Thorne’s retelling, Scrooge adamantly defends his actions until all the people he has hurt stage a kind of intervention. This Scrooge is not visited by a supernatural being but rather cranky therapists who force him into a 12-Step program. What should be expansive and joyful is frankly a bore.

All this is doubly frustrating because no lesser director than Matthew Warchus has created a wonderful Victorian setting and a sumptuous production. Unfortunately, what is obscured here is the human story. Broadway luminaries LaChanze and Andrea Martin as the Ghosts of Christmas Present and Past, respectively, are delightful, but Campbell Scott, as Scrooge, is disappointing — often manic but never menacing. His transformation is confusing, but that’s the script failing him.

“A Christmas Carol” will survive this interpretation, as it has many, many others. Still, in a version as weak and misguided as this, one leaves the theater not inspired but perhaps instead mindful of a variation on the book’s most famous line: “God help us, everyone.”

FOR COLORED GIRLS WHO HAVE CONSIDERED SUICIDE/WHEN THE RAINBOW IS ENUF | Public Theater, 475 Lafayette St., btwn. E. Fourth St. & Astor Pl. | Through Dec. 15: Tue.-Sun. at 8 p.m.; Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $75-$85 at publictheater.org or 212-967-7555 | Ninety mins., no intermission

TINA: THE TINA TURNER MUSICAL | Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, 205 W. 46th St. | Tue., Thu. at 7 p.m.; Wed., Fri.-Sat at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat. at 2 p.m.; Sun. at 3 p.m. | $99-$179 at ticketmaster.com or 800-653-8000 |Two hrs., 40 mins, with intermission

A CHRISTMAS CAROL | Lyceum Theatre, 149 W. 45th St. | Through Jan. 5: Tue.-Thu. at 7 p.m.; Fri.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat. at 2 p.m.; Sun. at 3 p.m. | $89-$169 at telecharge.com or 212-239-6200 | Two hrs., 15 mins., with intermission