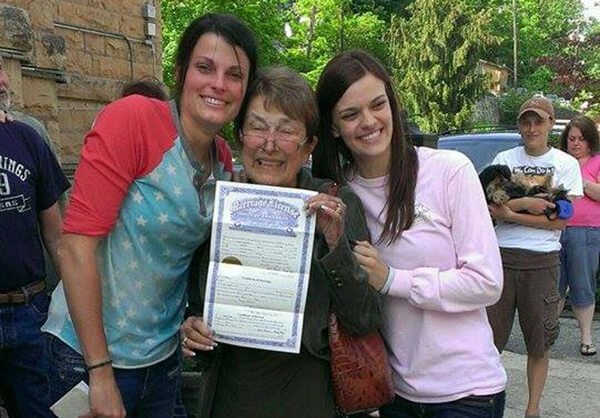

Kristin Seaton and Jennifer Rambo were the first couple to wed in Arkansas. | KENDALL WRIGHT/ COURTESY: FREEDOM TO MARRY

A state judge in Little Rock, Arkansas, relying on both that state’s constitution and the US Constitution, has struck down the ban on same-sex marriage there.

In a May 9 ruling, Pulaski County Circuit Judge Christopher Charles Piazza ruled the ban violates the 14th Amendment of the federal constitution as well as the Arkansas Constitution’s Declaration of Rights.

Piazza, who did not stay his ruling, waited until after county clerk offices statewide had closed on Friday afternoon to release his decision. The Pulaski County Clerk’s office announced it was prepared to begin issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples at the start of business on Monday morning, but some couples set their sights on the handful of counties whose offices are open on Saturday. According to the Associated Press, clerks in some of those counties said they had not formally been notified of the ruling and would not issue licenses to same-sex couples, but the AP also reported that licenses had begun to be issued in the Ozarks resort town of Eureka Springs in Carroll County, with Kristin Seaton, 27, and Jennifer Rambo, 26, being the first couple to wed.

Weddings begin as court cites federal and state questions of “epic constitutional dimensions”

The office of Democratic Attorney General Dustin McDaniel quickly filed a motion for a stay with Piazza, indicating it would file an immediate appeal with the Arkansas Supreme Court.

In the recent spate of marriage equality rulings, trial judges seem to be striving to out-do each other in their eloquence, and Piazza was no exception. He ended his opinion by referring to the US Supreme Court’s famous 1967 ruling in the Loving v. Virginia interracial marriage case, writing, “It has been over 40 years since Mildred Loving was given the right to marry the person of her choice. The hatred and fears have long since vanished and she and her husband lived full lives together; so it will be for the same-sex couples. It is time to let that beacon of freedom shine brighter on all our brothers and sisters. We will be stronger for it.”

Although the courts in two states — New Jersey and New Mexico — have produced marriage equality decisions since the Supreme Court last summer struck down the Defense of Marriage Act’s ban on federal recognition of legal gay marriages, Piazza’s decision was the first to do so on both federal and state grounds in a state with an anti-gay marriage constitutional amendment.

The amendment was enacted in 2004 as part of Karl Rove’s campaign strategy to re-elect George W. Bush by drawing conservative voters to the polls with anti-gay marriage initiatives. That strategy was fueled by reaction to the ruling out of Massachusetts in November 2003 allowing same-sex couples to marry there as well as to San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom’s short-lived drive in early 2004 to allow such marriages there, which set off copy-cat actions in some localities in New York, New Mexico, and Oregon.

The Arkansas amendment, which put into the State Constitution a ban enacted by statute a decade before, won the support of three-quarters of the voters, and that overwhelming margin was cited as the centerpiece of the state’s defense of its ban in arguments before Piazza.

The judge, however, concluded that the 2004 vote was “an unconstitutional attempt to narrow the definition of equality. The exclusion of a minority for no rational reason is a dangerous precedent. Furthermore, the fact that Amendment 83 was popular with voters does not protect it from constitutional scrutiny as to federal rights.”

Then, citing the US Supreme Court’s 1943 ruling that Congress could not enact a law to compel religious objectors to salute the flag, Piazza wrote, “The Constitution guarantees that all citizens have certain fundamental rights. These rights vest in every person over whom the Constitution has authority and, because they are so important, an individual’s fundamental rights ‘may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections.’”

The US Supreme Court, Piazza found, has repeatedly characterized the right to marry as a fundamental right and therefore any discriminatory law limiting that right must be subjected to a “heightened level” of judicial scrutiny. As with other recent judges ruling on marriage equality claims, however, he found that Arkansas’ ban could not survive even the most deferential standard of review.

“Regardless of the level of review required,” he wrote, “Arkansas’ marriage laws discriminate against same-sex couples in violation of the Equal Protection Clause because they do not advance any conceivable legitimate state interest.”

Piazza relied heavily on the Supreme Court’s DOMA ruling last year as well as the 1967 Loving ruling, and also quoted from recent marriage equality rulings by federal district courts. All of the cases cited by the state in defending its ban, he noted, pre-dated last year’s DOMA decision.

“The issues presented in the case at bar are of epic constitutional dimensions,” he wrote, saying his responsibility was to “reconcile the ancient view of marriage as between one man and one woman, held by most citizens of this and many other states, against a small, politically unpopular group of same-sex couples who seek to be afforded that same right to marry.”

It is difficult, he wrote, “to find a legal label for what transpired” in the high court’s DOMA ruling, but, quoting from the recent federal district court decision striking down Oklahoma’s gay marriage ban, he stated, “This court knows a rhetorical shift when it sees one.”

Acknowledging the likelihood that his ruling will not be popular among Arkansas voters, Piazza wrote, “The court is not unmindful of the criticism that judges should not be super legislators. However, the issue at hand is the fundamental right to marry being denied to an unpopular minority. Our judiciary has failed such groups in the past.”

The judge also cited recent decisions by the Arkansas Supreme Court in favor of gay rights, bolstering his conclusion that the State Constitution’s equal protection clause also justifies his ruling. In 2002, that court declared the state’s sodomy law unconstitutional and, in 2011, struck down a state policy prohibiting unmarried opposite-sex and same-sex couples from adopting children, finding there was no rational basis for it.

“The exclusion of same-sex couples from marriage for no rational basis violates the fundamental right to privacy and equal protection described in” those earlier State Supreme Court rulings, Piazza found, adding, “The difference between opposite-sex and same-sex families is within the privacy of their homes.”

The 20 same-sex couples who comprise the plaintiffs in this case include 12 who wish to marry and eight who are seeking to have their out-of-state marriages recognized. Piazza’s ruling focused almost entirely on the right to marry, providing no separate analysis on the recognition issue. But his emphasis on the state’s impermissible discrimination against same-sex couples logically applies to both situations.

Arkansas Assistant Attorney General Colin R. Jorgensen’s motion for a stay pointed to the US Supreme Court’s action in January that halted marriages in Utah while the appellate process plays out there. Quoting from a different Supreme Court ruling, he wrote that the high court grants a stay if there is “a fair prospect that a majority of the Court will vote to reverse the judgment below.” Given the court’s action on Utah, then, he concluded that “the Supreme Court has already indicated the likelihood” that Arkansas’ marriage ban will be upheld. Whether that conclusion on Jorgensen’s part is warranted –– and whether it will be persuasive on the question of a stay with either Piazza or any higher court in Arkansas –– remains to be seen.