The legendary musical “Lady in the Dark” (music by Kurt Weill, lyrics Ira Gershwin, book by Moss Hart) opened on Broadway in 1941. The incandescent Gertrude Lawrence starred as fashion editor Liza Elliott and an unknown comic Danny Kaye debuted as her fey staff photographer Russell Paxton. On a mid-spring weekend, MasterVoices presented three performances of a semi-staged concert version of “Lady in the Dark” at City Center featuring Victoria Clark as Liza. This was also the debut of the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music’s critical edition of the Kurt Weill/ Ira Gershwin score.

In its way, “Lady in the Dark” created just as much of a game-changing revolution in musical theater as “Show Boat” (1927) and “Oklahoma!,” which opened two years after “Lady” in 1943. What was revealed in this concert performance is that this now-rare musical landmark is something of an odd duck. Hart, inspired by his own experiences in analysis, originally conceived “Lady in the Dark” as a straight play starring Katharine Cornell with one or two interpolated songs. Liza Elliott, a busy editor of a fashion magazine, finds herself suffering from disturbing musical dreams and public emotional breakdowns. She seeks out Dr. Brooks, a psychiatrist, to sort out her personal and romantic dilemmas. (Liza is cured in three sessions!) However, as Hart worked on it, the dream scenes began to expand in scope and became fully musicalized. Enter Weill and Gershwin.

These musical sequences are not so much diegetic as dreamagetic — the characters only sing in Liza’s dreams, which explore her repressed fantasies. The three extended musical dream sequences — “The Glamour Dream” and “The Wedding Dream” in Act I and the “The Circus Dream” in Act II — dropped into a talky “Freud for Dummies” women’s drama make for odd musical and dramatic continuity. The musical numbers aren’t integrated into the plot (as in Rodgers & Hammerstein) but are Brechtian vaudevilles that comment on it sardonically. The scintillating word play of Ira Gershwin’s ingenious lyrics (in his first collaboration since the death of his brother George) rival and often outstrip his contemporary Cole Porter and show a clear influence on Stephen Sondheim (internal rhymes, and the like). Weill keeps playing with conventional music comedy tropes turning them on their head. Weill’s sophisticated “Lady” was a “concept musical” way before that term was invented.

One thing that has made the show difficult to revive is the outmoded attitude toward a woman’s role in society in Hart’s book. Similar to Hollywood movies of the period, a woman who attempts to be independent and successful in a man’s world is doomed to sexual frustration and loneliness. In 1941, Liza had to cede her power to the man she loves, Charley Johnson, before she can find personal fulfillment. An abridged 1950 radio broadcast of the show with Gertrude Lawrence (briefly available on an AEI CD) clearly shows the leading lady playing against that trope: In the final scene, where Liza and Charley plan their new magazine, Lawrence as Liza knowingly uses her soft female charms to control him with seductive charm.

In the script edited for this 2019 concert by Christopher Hart and Kim Kowalke, Liza and Charley are equally matched. Charley’s innovative ideas inspire Liza, who provides the experience and savoir faire to temper his brashness and realize his ideas. Also, Dr. Brooks is recast as a maternal female psychiatrist, warmly played by Amy Irving, rather than a paternalistic male doctor.

Victoria Clark initially seemed too down to earth as the nerve-ridden Liza but her warm mezzo-soprano voice and theatrical intelligence illuminated the words and music. Clark also has the ability to wear clothing stylishly, which was useful modeling the gowns by Thom Browne, Zac Posen, and Marchesa in the dream sequences where Plain Jane Liza turns into an irresistible temptress.

The men in her life (and dreams) included David Pittu as a drolly mercurial gay photographer Russell Paxton (who is portrayed as a pre-Stonewall comedic swish). Pittu gives Russell all kinds of darkly surprising edges in all his personas and nailed the tongue-twisting patter in “Tchaikovsky.” Christopher Innvar found an interesting subtext of male insecurity and boyish vulnerability in the abrasive Charley Johnson. Ben Davis’ booming baritone, chiseled profile, and manly chest fit Hollywood hunk Randy Curtis to a tee. Ron Raines as Kendall Nesbitt, Liza’s married publisher lover, was a strong presence with a strong voice to match. Montego Glover and Ashley Park were brightly adroit and musically impeccable as Liza’s office colleagues. Ideally, this cast should have been recorded with supplements from the critical edition.

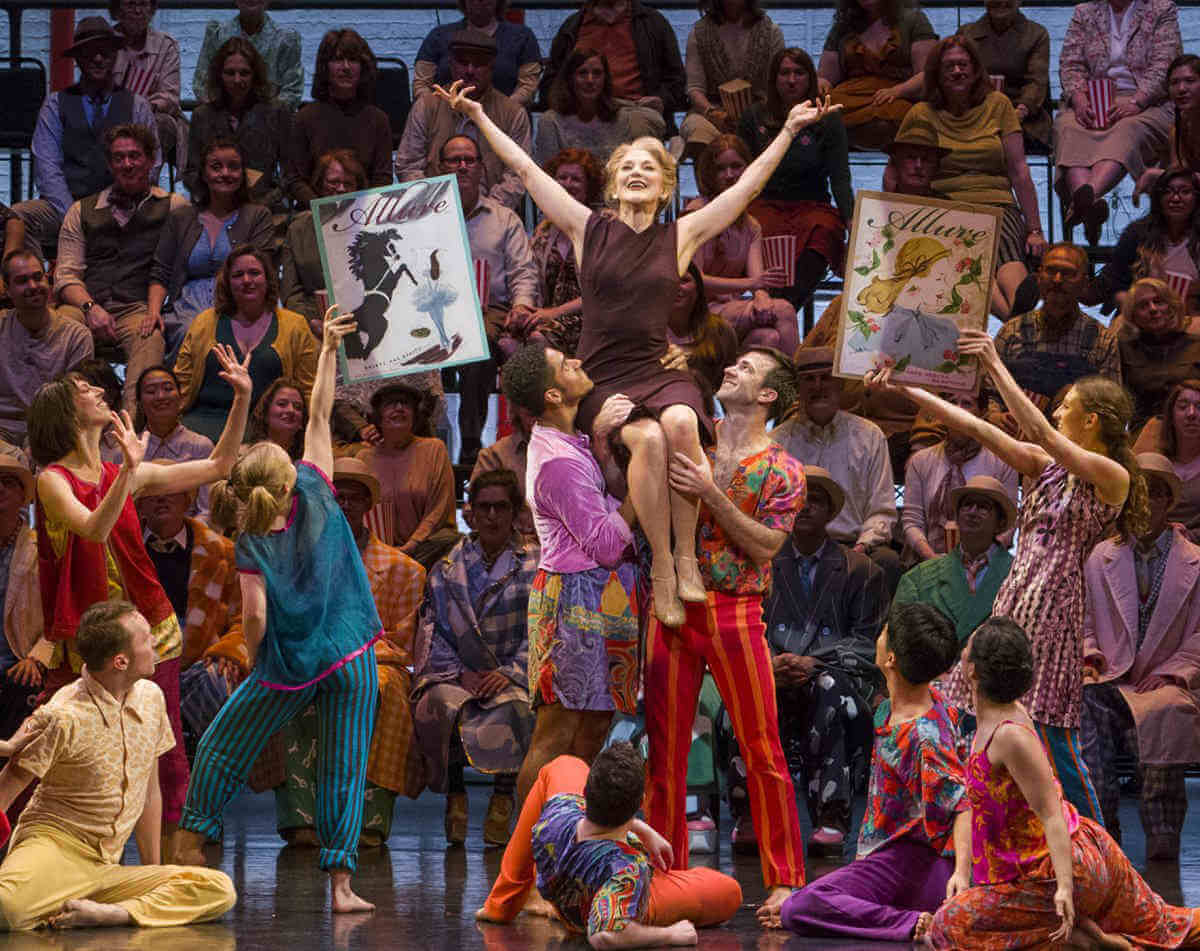

Ted Sperling led the Orchestra of St. Luke’s in a magnificently realized reading of the score — the voices were all excellent and the overlarge chorus impressively drilled. Doug Fitch provided easily movable sets that went from “black and white” subdued tones in the book scenes to jewel-toned Technicolor in the musical dream sequences. Doug Varone added a dash of modern dance eccentricity to his choreography, and his dancers moved from period specific to post-modern funky with élan. “Lady in the Dark” came out from the shadows of obscurity and was once again the toast of New York — if only for one long weekend.