Family joins Newark’s activists in honoring young lesbian

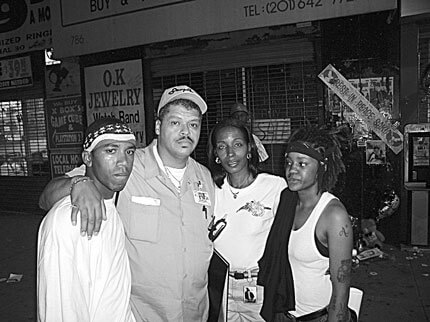

On the evening of Tuesday, May 11, hundreds of New Jersey residents gathered in Newark to mark the first anniversary of the death of Sakia Gunn, a 15-year-old lesbian who rebuffed a man’s sexual advances before he stabbed her. On a balmy evening, not unlike the night she was killed, Sakia’s friends and family thronged the intersection of Market and Broad Streets to remember a young woman who proudly identified as a lesbian.

“Many of our African American people have strayed away from the heritage of our ancestors,” said Laquetta Nelson during a speech in which Nelson denounced violence against women and decried the media’s lack of coverage of the killing of Sakia Gunn, unlike the national coverage given to the murder of Matthew Shepard in 1998, Nelson said. Shepard, a white college student, was killed by two men who met him in a bar in Laramie, Wyoming, and then drove the young man to the countryside where they beat him and left him tied to a fence. Shepard later died in the hospital and his death became a rallying cry for the passage of hate crimes legislation and tolerance for gay Americans.

Nelson, along with other LGBT advocates, founded the Newark Pride Alliance after Gunn’s murder and has advocated on behalf of the city’s LGBT youth.

On Tuesday night, Nelson read from a proclamation signed by Gov. Jim McGreevy, in which the Democrat memorialized Sakia Gunn and underscored his support for gay and lesbian rights.

Earlier on Tuesday, Newark’s school principals honored Gunn with a moment of silence and then recited the names of those public school students who died in the past year.

According to the Star Ledger of New Jersey, six students from Gunn’s former school, West Side High School, have died within the past 18 months.

The scene on Tuesday night in Newark resembled the large gathering of young people who assembled at the same spot last year upon hearing of the young lesbian’s murder. Mourners erected a makeshift shrine and posted photographs of Gunn from happier times, in her basketball clothes and junior high school cap and gown.

Thelma Gunn, the grandmother of Sakia, attended Tuesday night’s vigil. A year ago, the elder Gunn was rushed to University Hospital upon hearing of her granddaughter’s death and was treated in the same emergency room where earlier that evening Sakia had expired after rapidly losing blood from her stab wound.

Thelma Gunn declined to be interviewed, but she did express a lingering sorrow for her missing granddaughter, as did many other family members of Sakia who turned out as they did a year ago to mourn her death.

Following the murder, a group of residents demanded that the city offer outreach services to Newark’s gay and lesbian youth, particularly in light of the enormous outpouring of grief manifested during a march on city hall and at Sakia’s funeral, where over 2,500 mourners filled the street outside the funeral home.

Richard McCullough, who has been held as a murder suspect since the week after the crime, is scheduled to go on trial this summer. The Essex County prosecutor also plans on trying McCullough under the state’s hate crime statute, which mandates enhanced sentencing upon conviction. Another man was present in the car with McCullough when the two allegedly drove up and began talking with Gunn and four of her friends as the girls waited for a bus after a night socializing Greenwich Village. Authorities have never identified that second man, leading to the supposition that he is cooperating in McCullough’s prosecution.

Mayor Sharpe James, a Democrat, attended Gunn’s funeral, but has never honored the pledge he made publicly to the throngs of young mourners when he told them the city would establish a center for Newark’s LGBT adolescents.

However, in a surprise announcement last month, the state-appointed superintendent of schools for Newark, Marion Bolden, favorably answered Nelson’s request to honor the first anniversary of Gunn’s death with “No Name Calling Day,” an initiative meant to instill tolerance in the schools for LGBT youth and provide sensitivity training to the pedagogical staff. Many of the young lesbians in Newark’s schools have reported, for example, that school officials have prohibited the wearing of freedom necklaces and bracelets, strands of brightly colored beads representing the colors of gay liberation, equating such homemade jewelry with gang insignia.

Last year, according to some West Side High School students who showed up at Gunn’s funeral, Fernand Williams, West Side’s principal, made a disparaging remark about gay people and forbid according Gunn a moment of silence during school hours.

Williams never returned phone calls seeking his comment on the charges.

On May 11, 2004, according to the Associated Press, Williams said he never denied the moment of silence request and he acknowledged that he has avoided speaking about Gunn’s death in order to avoid exacerbating the grief over her murder. “It was difficult for me to open up the school to the media because I didn’t want to open up some of the wounds [the students] are trying to heal,” said Williams.

Since her death, a chapter of Parents, Friends and Families of Gays and Lesbians, a national group with a large membership, was formed in Newark. The group established a Sakia Gunn college scholarship and named its first recipient, Alexa Punnamkuzhyil of Arcata, California, a high school senior, for her work on behalf of LGBT awareness and non-violence.

However, the wounds caused by Gunn’s death are still healing. Marces Dixon, Sakia’s half-brother and a high school student, said that he still has trouble concentrating in school and that he will need to attend summer school in order to get his high school diploma. “I’m doing stuff now I know I shouldn’t be doing,” said Dixon, “like beating up on people.”

Another young man, who never knew Gunn, held aloft a lit candle during her vigil and said the young lesbian’s death forced him to be honest about his sexuality. “It’s hard to be gay, period—black or white,” said Kareem Clemmons, 22. “Sakia’s death had a profound effect on me. She was gay herself and she might not have been family, but she is family to me. When somebody asks me if I am gay, I have to say I’m gay now.”

One young lesbian, Linda Jemah, 22, said that African American people always face the challenge of being misrepresented in the media. “The media sensationalizes violent stories like the Bloods and Crips, but not positive events like this,” she said.