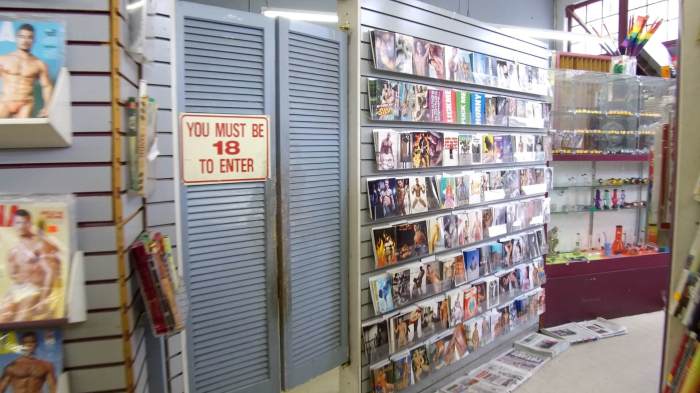

Rachel Mason’s “Circus of Books,” now streaming on Netflix, begins by introducing us to her parents, a now-elderly couple. She films them sitting on a couch in their house, while cutting in home movies of the family’s beach outings in the 1970s. The elephant in the room quickly steps out of the shadows to clear up these scenes’ slight awkwardness: her parents have made a living running Circus of Books, a Los Angeles store that sold gay porn beginning in 1976. In the ‘80s they became involved with distributing and producing it.

Circus of Books became a community center and a sex club. In the ‘70s, the lines between adult movies and “mainstream” queer art were far more blurred than they are now. If American directors wanted to make films like “My Own Private Idaho,” “My Beautiful Laundrette,” or “Poison” at that time, they had few opportunities to do so, so many talented gay filmmakers wound up directing hardcore porn. Arthur J. Bressan moved back and forth between it, documentaries, and narrative features. The fact that folks had to pay to go a theater and sit down to watch porn in the ‘70s — even if they left after achieving orgasm — meant that narrative ambition was compatible with extremely explicit sex.

Karen and Barry Mason weren’t especially interested in gay porn. He had gone to film school with Jim Morrison and worked on the special effects of “2001: A Space Odyssey” and “Star Trek,” but in the ‘70s, he needed a new way to earn an income. Karen shows her daughter a list of titles whose profits paid for her college education. While the idea of funding school off titles like “Confessions of a 2-Dick Slut” might make one guffaw, Karen also says that she never watched the films the couple produced. She treats the sex business with detachment, buying sex toys as though she were selecting any old merchandise.

The Masons became the distributor for Hustler magazine and other Larry Flynt publications, including the gay Blueboy. “Circus of Books” interviews Flynt about this period. Feminist author Laura Kipnis has written that contrary to the depiction of the man as a free speech pioneer in Milos Forman’s “The People vs. Larry Flynt,” the real value of Hustler lay in its very embrace of offensiveness and what we’d now call trolling, connecting “bourgeois bodily discretion to political and social hypocrisy.” “Circus of Books” winds up domesticating porn, literally turning it into a middle-class family business. But in this context, its very wholesomeness and optimism are subversive.

The film also depicts a time when a lack of discretion could make you a social pariah or even get you arrested. Karen struggled to reconcile her work with her conservative Jewish values. The Masons were very cagey about which friends they told what they did, and even the most “tolerant” seemed to approve only on a partial basis. Sound familiar? At a time when the majority of gay men had to stay in the closet, the Masons wound up in that same closet. A more serious problem arose when they got caught up in the Reagan administration’s attempt to censor porn, with Barry getting prosecuted for shipping five videotapes to Pennsylvania.

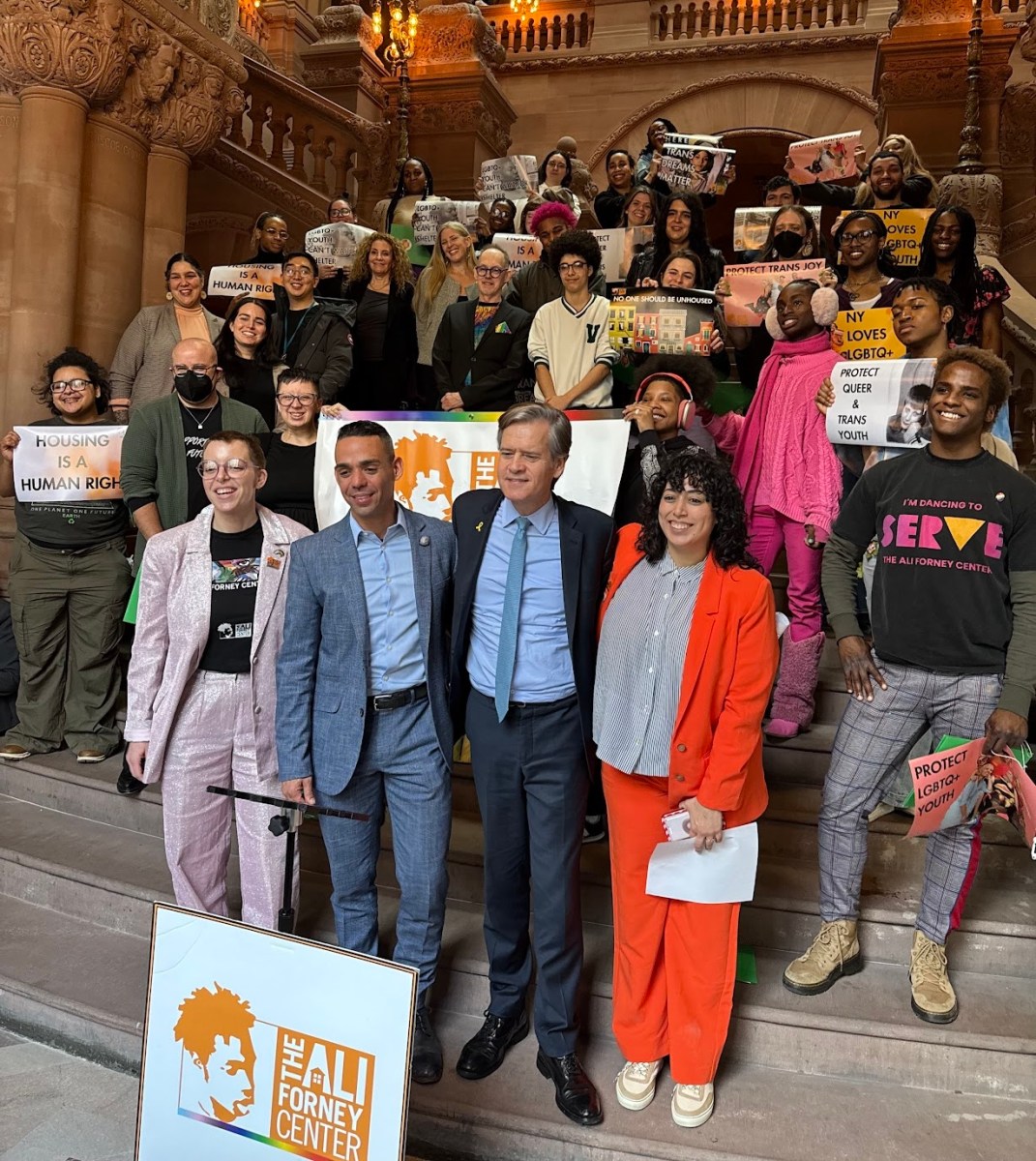

In its last half, “Circus of Books’ becomes a more personal story. Rachel does not reveal much about herself. But she explores the way her family compartmentalized things. Her mother’s contradictions came to a breaking point when Rachel’s brother Josh came out. Rachel is queer herself, and she mentions that her circle of punk and artist friends in high school might have been “too gay,” scaring her more conventional brother away from accepting his identity. But the fact that her own son is gay broke down barriers Karen had established in her mind, where she felt okay making money off gay men but still thought being gay was wrong on some level. After initial reluctance, the Masons joined PFLAG and participated in Pride Parades.

That’s a heartwarming, uplifting story. But the other arc of “Circus of Books” is a downward trajectory. Rachel films the business shutting down. Thanks to Pornhub and the ubiquity of porn online elsewhere, one can watch vast quantities of it without ever going outside, much less buying magazines and DVDs. But that’s led to the death of community represented by bars and places like Circus of Books. In the ‘80s, the store was notorious for its “Vaseline Alley,” and one worker remembers having sex in its attic. The possibilities for human connection inherent even in the most casual sex have moved online. “Circus of Books” describes the ways that retail stores can forge community, rather than just being capitalist outposts, and suggests what we’ve lost now that we’re trapped at home — involuntarily now, but so often voluntarily.