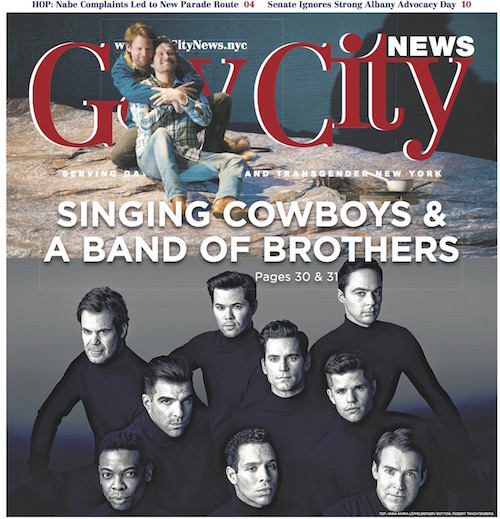

Kevin Short and Kristin Sampson in “La Fanciulla del West,” which the New York City Opera co-produced with companies in North Carolina and Italy. | SARAH SHATZ

BY ELI JACOBSON | New York City Opera launched its 2017-2018 season on September 6 with a colorful, ambitious, and largely successful new production of Puccini’s “American” opera, “La Fanciulla del West” (“The Girl of the Golden West”). Consistent with the current NYCO business model, this “Fanciulla” is an international co-production with the Teatro di Giglio in Lucca, Italy, the Teatro Lirico in Cagliari, Sardinia, and Opera Carolina. The production premiered in Charlotte earlier this year, then after this week’s four performances at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater, it will move overseas to Italy.

Puccini’s intriguing mashup of oater and polenta takes a David Belasco Western melodrama set during the 1840s California Gold Rush and pours on the red sauce Italian verismo. This exotic dish is seasoned with refined French impressionist and post-Wagnerian German orchestral writing. Melodrama is the shared element among these incongruous ingredients. It should be ridiculous — and sometimes is — but it all works like gangbusters with the right singers, the right spirit, a fine orchestra, and a convincing, theatrically dynamic staging. City Opera provided most of these elements in somewhat unfinished form — but with the right spirit in abundance.

Ivan Stefanutti directs and designed the production, which combines simple bare bones set pieces, furniture, and props with stage-filling visual projections. The unit set consists of a curved wooden platform upstage with movable set pieces added in each act (a staircase for the Polka Saloon in Act I, the loft in Minnie’s cabin for Johnson/ Ramerrez to hide in during Act II, and a hangman’s gallows in Act III). Visual projections (designed by Stefanutti and realized by Michael Baumgarten, the lighting designer) create cinematic effects with an emphasis on nature.

Winning co-production of Puccini’s Gold Rush spaghetti Western

The opening filmic montage set to the opera’s prelude introduces us to aerial views of the snow-covered Sierra Mountains and a “wanted” poster of the bandit Ramerrez, which the tenor anti-hero passes by in silhouette. Projections indicating interiors change according to the moods of the characters: when the homesick miners sing of their faraway homes we see farmlands, and the poker scene is backed by a wall of playing cards. There are no walls, which gives a sense of wide open space, a set-up that fits the shallow but wide Rose Theater stage perfectly. Minnie does not ride in on a horse in Act III but otherwise everything is there, and Stefanutti’s choices are mostly sensible and work theatrically.

Opera Carolina’s general director and principal conductor James Meena presided over an occasionally unfocused, uncoordinated but idiomatic performance that gained in power and assurance over the evening. In Act I, ragged ensemble and false entrances plagued the male soloists, orchestra, and chorus, and Kristin Sampson as the gun toting barmaid Minnie seemed to get lost during the final duet, dropping a phrase or two. Repetition over the run should correct these faults. The male voices were impressively strong — several of the miners were familiar from leading roles with small local opera companies. Newcomer Alexander Birch Elliott cut a handsome figure as Sonora, pleasing the ear with a mellow lyric baritone, while bass-baritone Christopher Job as Ashby commanded his limited moments on stage. Tenor Michael Boley as the bartender Nick gave an alert, subtle performance.

Jonathan Burton and Kristin Sampson in “La Fanciulla del West.” | SARAH SHATZ

The opposing rivals for Minnie’s affection were cast with strong voices: Kevin Short lavished rich, mahogany velvet bass-baritone timbre on Sheriff Jack Rance’s higher-lying baritone music. As the bandit Ramerrez (aka Dick Johnson), debutant Jonathan Burton deployed an impressively bright, tireless tenor that lacked sensuous color and nuance but easily conquered all the treacherous passages in the role. Tall and burly, the affable American tenor seemed confident onstage (but not mysterious, dashing, or sinister) and gave a stirring account of his Act III aria “Ch’ella mi creda.”

“Fanciulla” depends on the success of the titular character, the “girl” Minnie. A Dicapo stalwart back in the day, Kristin Sampson as Minnie initially made a tentative, uncharismatic impression. Minnie’s first entrance shooting her rifle into the air to break up the brawling miners’ bar fight is usually a surefire showstopper. Sampson ambled diffidently onstage at the top of the staircase and fired her shots out of sync with the action and the music. Acting-wise, Minnie needs either plenty of gutsy tough-gal bravado or winsome charm — and preferably a combination of both. The petite Sampson lacked either quality and was deficient in stage presence and vibrant personality. Hands on hips, this saloon gal was all business. Vocally, Minnie requires the soprano to swing unprepared from chesty low voice declamation to soaring high soprano lines. Sampson’s lirico-spinto soprano sounded hollow and pressed on the bottom yet confidently nailed the many out-of-nowhere forte high B’s and C’s with an appropriate hint of metallic edge. But Sampson was efficient rather than commanding and lacked vocal warmth.

In Act II, the soprano, orchestra, and production pulled together with greater musical and dramatic focus. Sampson and Burton impressed in a rarely performed, murderously difficult extended version of the Act II love duet (added by Puccini for a 1922 Rome revival), where several bars of “Tristan”-like high declamation culminate with the soprano and tenor holding a fortissimo high C in unison. Sampson and Short ended the act with a sizzling performance of the famous “Poker Scene. The commitment of the ensemble scored enough points to make NYCO’s “Fanciulla del West” production a winning hand.