For the theme of his latest exhibition, “Havana,” the artist Kehinde Wiley has selected the carnivalesque. And, indeed, last Thursday’s opening at Sean Kelly Gallery was in-keeping with the theme. Visitors delighted in matching their outfits to the rich patterns and vivid colors of Wiley’s characteristic brush. “Is his brother here?” a leather-jacketed woman said aloud to her companion, casting glances through the crowd. “You know he has a twin brother, don’t you?”

When Wiley made his entrance, guests swarmed him. WCBS anchorman Maurice DuBois stood amidst the throng, calmly waiting for the deluge to subside. It is not the norm for the rarefied world of visual art to be transported to the living rooms of America via a news at 5 broadcast. But, such is the world of Kehinde Wiley, a world in which, as the artist’s statement for “Havana” purports, “depictions of the circus offer a type of self-portraiture.”

“Havana” comprises portrait paintings of singles and pairs, works on paper, and a quasi-documentary film installation. All of the subjects are circus performers or dancers with whom Wiley spent time during two separate visits to Cuba. In 2015’s visit, he was introduced to the Escuela Nacional de Circo, the national circus training school. On the 2022 visit, he spent time with members of Raices Profundas (translated to “deep roots”), an Afro-Cuban dance company globally recognized for carrying on traditions inherited from the Yoruba people of West Africa. Wiley’s encounters with both troupes inspired him to visualize on the canvas and screen the ways in which circuses and carnivals have historically provided African-heritage people “moments of freedom and grace.”

The film installation is presented as three different channels, showing three angles of the same documentary of Raices Profundas in performance. On the left screen, the troupe, clad in brightly colored costumes, is shown dancing. On the right screen are interviews with each dancer. On the center screen run scenes of the built environment — the interior of a fort, the famous Malecón seawall, a narrow street, a pool, and so forth. The result is a palimpsestic effect whereby the viewer experiences layers of overlaid perspectives, part ethnography, part elegy.

“Black people are survivors, we’re shapeshifters,” Wiley asserts in this show’s exhibition statement.

Consistent with Wiley’s practice of taking on the most canonic artists and sacred figurations in the history of Western art, “Havana” contains references to works by painters Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Pablo Picasso, sculptor Alexander Calder, as well as to familiar Western European depictions of the carnivalesque and the circus.

The majesty Western painting has historically reserved for nobles and the divine is, on Wiley’s canvasses, granted to circus performers and dancers “who embrace a dynamic and vibrant way of living and being in the world.”

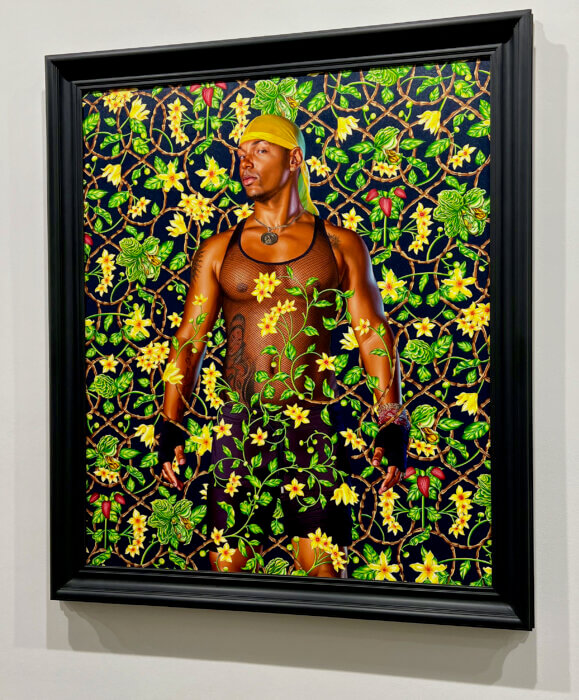

A juggler holds his clubs, a duo of acrobats strikes a pose with one atop the other’s shoulders, two dancers sit side-by-side but gaze off in opposite directions, their bright headdresses and gowns flooding the canvas with luminosity. In “Portrait of Emilio Hernandez Gonzalez,” the subject is clad in a neon yellow durag, black mesh vest under which tattoos, areolas, and belly button are invitingly visible. A vine with delicate yellow flowers snakes around his body, and, to the viewer, he shoots a seductive side-eye.

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is a professor of journalism and media studies at Lehman College of the City University of New York (CUNY). Follow him on Twitter @DrNickBoston and Instagram @Nick_Boston_in_New York