Federal administrations in their final days usually rush to put in place regulations intended to codify their policy preferences, in some cases racing the clock to put the final touches on measures long under development. The Trump administration was no exception, rushing to the Federal Register several regulations and rules intended to overturn Obama administration policies and to provide a narrow spin on LGBTQ courtroom victories.

Notable among new Trump regulations in recent months are revisions to the rules governing asylum for foreign refugees, narrow interpretations of the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling from last June in Bostock v. Clayton County, and broad interpretations of constitutional and statutory protection for free exercise of religion to excuse compliance with anti-discrimination laws.

The Biden administration and the new Democrat-controlled Congress have various mechanisms at hand to cancel much of the last-minute rule-making.

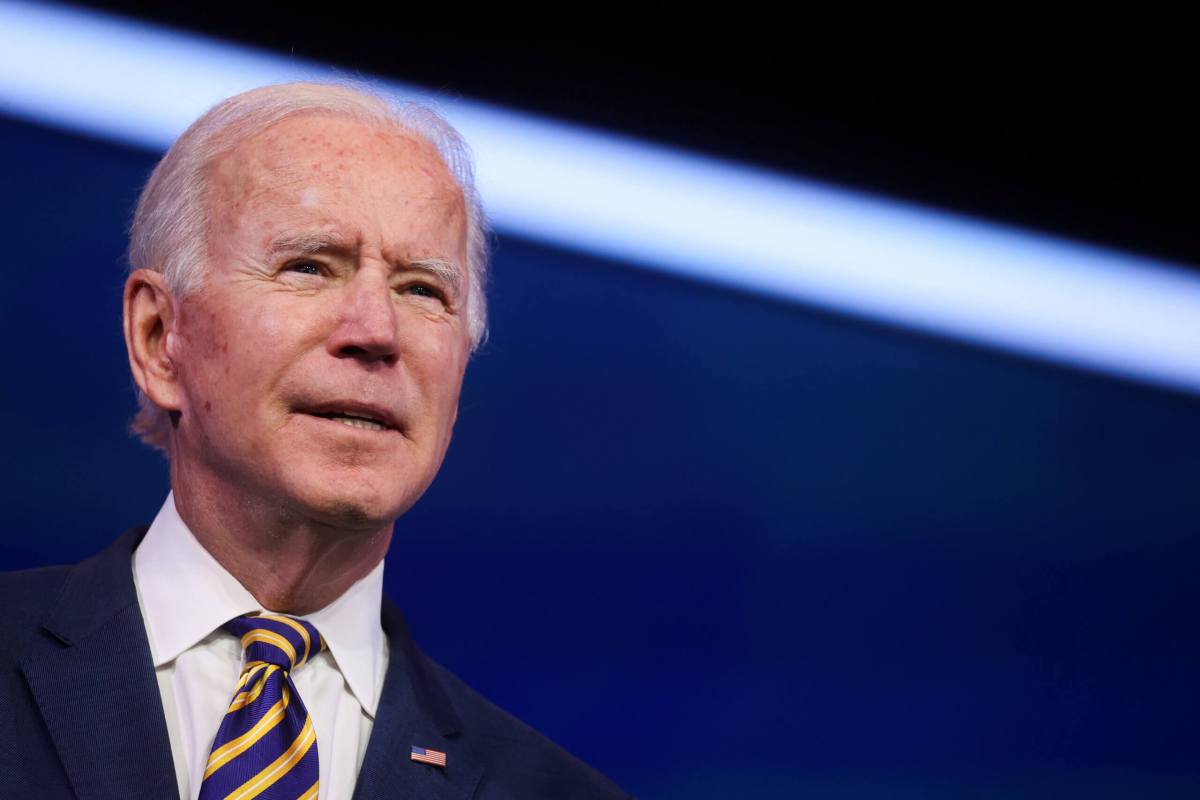

Donald Trump’s executive orders and formal written directives can be rescinded by President Joe Biden with the stroke of a pen. For example, Trump’s ban on transgender service members, which has never been embodied in a statute or a formal regulation adopted under the Administrative Procedure Act, can simply be revoked by the new President and replaced with a non-discrimination policy, although the details would need to be worked out with the new leadership in the Defense Department.

Some of the Trump administration regulations have been announced and published as “final rules” but have been blocked from implementation by court orders. For example, a regulation altering the substantive and procedural rules for dealing with refugees was recently blocked by a preliminary injunction while a court determines whether it is consistent with the relevant statutes.

This regulation would have made it very difficult for gay refugees to win the right to remain in the United States. The new administration can go through the APA procedure for replacing it with a new regulation, but under the Congressional Review Act, a 1996 statute that was the brainchild of Newt Gingrich when he became Speaker of the House of Representatives in 1995, recently-adopted regulations can be repealed by Congress with simple majority votes in both houses and the approval of the president, with no Senate filibusters allowed.

There is a time limit, however, of 60 legislative days from the date Congress was informed of a new regulation or rule (a legislative day is a day when Congress is in session, so many weekends, holidays, and periods of legislative recess, are not counted). During the early months of the Trump administration, more than a dozen Obama administration regulations adopted during 2016 were repealed using the CRA.

Similarly, a Trump administration regulation excluding transgender people from protection under the Affordable Care Act’s anti-discrimination provision has been preliminarily enjoined in litigation but could be withdrawn and replaced by the new administration through administrative action or, possibly, repealed under the CRA.

One prime target for CRA repeal action should be a new regulation that was slated to go into effect just days before the inauguration. The regulation sharply restricts Obama administration anti-discrimination rules for federal contractors and funding recipients, allowing those with religious or moral objections to deny services to LGBTQ people and to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages. The Trump administration supported this regulation by arguing that requiring federal contractors to violate their religious beliefs was illegal under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

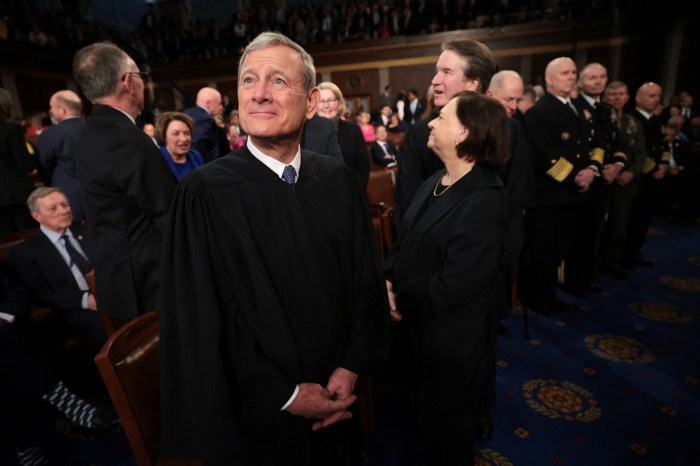

Although Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch mentioned RFRA in his decision for the Court in Bostock, the question whether RFRA was applicable to a Title VII employment discrimination claim was not directly presented to the Supreme Court in that case, so Gorsuch’s comments are not part of the Bostock precedent. Furthermore, Gorsuch did not directly state that RFRA would invalidate every application of federal law over religious objections.

Repealing the new regulation would free the Biden administration to take its own interpretative approach to the complicated question of the relationship of RFRA and federal anti-discrimination policies, a question that has not yet been definitively resolved by the courts.

Some Trump administration policies can simply be reversed as part of the normal administrative processes of federal agencies. In August, the Office of Civil Rights in the Department of Education grudgingly recognized that under the Bostock decision, it was obligated to deal with gay students’ discrimination complaints under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, but the Department of Education refused to back away from its position that schools can treat students differently due to their “biological sex,” which tends to leave transgender students out in the cold in light of the Trump administration’s consistent disposition to question the validity of gender identity.

For example, the department has persisted in its view that transgender girls can be excluded from participating in girls’ sports programs and that transgender students can be restricted from using restroom and locker room facilities consistent with their gender identity. The new administration can rescind this administrative interpretation of the statute without going through time-consuming rule-making, just as the Trump administration quickly rescinded the Obama administration’s interpretation to the contrary early in 2017 when the government effectively “switched sides” in pending litigation over the issue.

The Bostock decision was written by the Supreme Court in such a way that it should be applicable to any federal policy that forbids discrimination because of sex, contrary to the position, for example, of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which has fought against claims that the Fair Housing Act requires homeless shelters to accommodate transgender people. Congress could override the HUD interpretation, or new administrators at HUD can issue new interpretive guidance to reverse it.

While passage of the Equality Act remains the primarily legislative goal for LGBTQ rights under the new administration, as it would expressly add “sexual orientation” and “gender identity or expression” as prohibited grounds for discrimination under existing federal anti-discrimination laws, much can be accomplished during the early months through new administrative rule-making, new executive orders, and Congressional action under the CRA. Democratic leaders in both houses of Congress should be strategizing with the new administration over which rules or regulations to repeal legislatively and which to leave to administrative action or presidential decrees.

Editor’s Note: On his first day in office, President Biden signed an Order directing the entire executive branch to comply with the Supreme Court’s ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County that claims of sex discrimination under Title VII necessarily include claims of sexual orientation or gender identity discrimination, and to apply that interpretation to all federal laws banning sex discrimination. The Trump Administration had refused to follow this route, seeking to confine Bostock to employment discrimination claims under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act.

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.