BY PAUL SCHINDLER | Just when it seemed that divisive feelings threatened to overwhelm the Democratic presidential primary contest, Hillary Clinton has assumed a commanding position in the race to this summer’s Philadelphia convention.

Clinton now has 1,650 pledged delegates, a 302-vote edge over Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders. Counting his 39 superdelegates, Sanders would have to earn 82 percent of the remaining 1,206 delegates yet to be chosen to win the nomination — impossible given the Democratic Party’s proportional primary voting system. He essentially is mathematically eliminated from contention, unless the Clinton campaign were to suffer such a calamitous collapse that Sanders’ surge in the remaining primaries convinced Hillary’s 519 superdelegates to abandon her on the basis of momentum and electability.

Nobody makes plans by relying on such far-fetched assumptions.

As partisans reconcile themselves to Clinton’s inevitability, it’s worth considering the role of the superdelegates, which have occasioned no small amount of controversy, not to mention some shifting arguments. There is a need for clarity on this point. As an outsider, Sanders watched Clinton pile up superdelegate endorsements early on and rightly criticized the anti-democratic power enjoyed by these party big-wigs. In the Republican Party, the primaries impose what is often a check on insurgents by making some contests winner-take-all. Democrats invite more voices through a proportional voting system, but then hedge that with superdelegates.

That said, Clinton is not ahead because she has the loyalty of superdelegates. She is well ahead on the pledged delegate front alone, having captured 55 percent of those elected to date. Early on, some Sanders supporters complained she would only reach the 2,383 needed for nomination because she has strong superdelegate support, but that would be true in any close contest. Put another way, if you take Clinton’s superdelegates out of the numerator in measuring her performance, you have to take all the superdelegates out of the denominator, as well. With a 302-delegate lead at this stage in the primary contest, it’s very hard to imagine she won’t arrive in Philadelphia with a comfortable pledged delegate advantage.

That should be the end of the discussion regarding superdelegates. Unfortunately it’s not, since the Sanders campaign has recently taken up the anti-democratic side of this debate, with top surrogates suggesting that superdelegates pay attention to polls showing the Vermont senator as the stronger general election candidate and step in to override the voters’ judgment. Hopefully that argument is just momentary grasping at straws by Sanders supporters unwilling to yet acknowledge defeat.

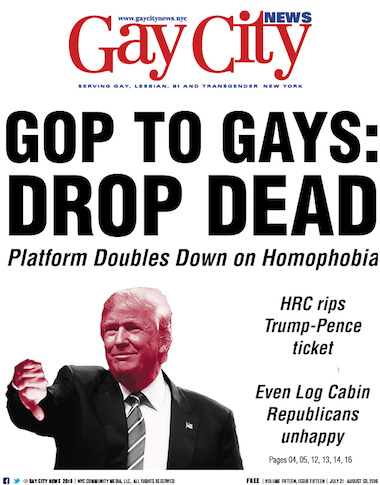

Hillary Clinton will be the Democratic nominee for president this year, and given the likelihood that Donald Trump will be her opponent — unless someone else, and maybe someone worse, yet finds a way to stop him — it is essential that voters concerned about this nation’s future rally to her side.

I won’t make the argument that Clinton is the perfect candidate. Though her disastrous Iraq War vote came well over a decade ago, it speaks to a hawkish instinct that could pose new and significant problems in what is, if anything, an even more perilous time than we faced in the wake of 9/ 11. I hope her fall campaign can spell out a foreign policy that embraces the US’ critical leadership role in the world, while acknowledging the limitations on our power and the cost of missteps. Clinton has been a player on the world stage for more than two decades, so she should be guided by her intelligence and gut rather than by domestic political challenges — which Trump is sure to raise this fall — about whether she is tough enough or has “stamina” enough for the job.

I won’t make the argument that Clinton is the perfect candidate. Though her disastrous Iraq War vote came well over a decade ago, it speaks to a hawkish instinct that could pose new and significant problems in what is, if anything, an even more perilous time than we faced in the wake of 9/ 11. I hope her fall campaign can spell out a foreign policy that embraces the US’ critical leadership role in the world, while acknowledging the limitations on our power and the cost of missteps. Clinton has been a player on the world stage for more than two decades, so she should be guided by her intelligence and gut rather than by domestic political challenges — which Trump is sure to raise this fall — about whether she is tough enough or has “stamina” enough for the job.

Clinton has also been prone during her career to serious unforced errors. The two that have bogged her down during this year’s campaign are her use of a private email server while secretary of state and her acceptance of fees in the hundreds of thousands of dollars for speeches given to Goldman Sachs audiences. That second issue has, of course, fueled the doubts Sanders has raised about her commitment to meaningful Wall Street reform. In refusing to release transcripts of those speeches — inexplicable given the unlikelihood she said anything all that politically damning in a well-attended, quasi-public setting like a corporate dinner — she has allowed symbolism to overwhelm a detailed and substantive discussion of her differences with Sanders on regulatory questions. Sanders couldn’t help but get the better of that situation.

Sanders seems certain to carry on his campaign, at least through California and New Jersey in early June and likely to Philadelphia. That is his right, and the party and the nation have profited from his focus on economic inequality. The Democrats’ failure to address that issue head on has hobbled them for years in reaching economically marginal segments of society — some of them now drawn to Trump’s demagoguery — that deserve to have their interests addressed. Sanders proved that economic populism can be a winning political formula.

But Sanders and especially some of his more ardent supporters do the party and the nation a disservice by focusing on poll-tested attacks on Clinton’s character. Her private email server was ill-advised, but there is not even a remotely indictable offense involved there. She showed poor judgment and insensitivity to what the average American faces in accepting big Wall Street fees even as she planned to run for president, but there is no evidence of any quid pro quo involved there. And chatter among at least some progressives about Clinton’s “betrayal” at Benghazi is beyond the pale on an issue that the GOP has squeezed and squeezed and squeezed with no substantive results.

The simple fact is that America this November faces a straightforward choice between moving forward to a more just society while addressing the significant economic, environmental, and international challenges facing us or taking a big and potentially disastrous step backward. That’s an easy choice: Hillary Clinton.