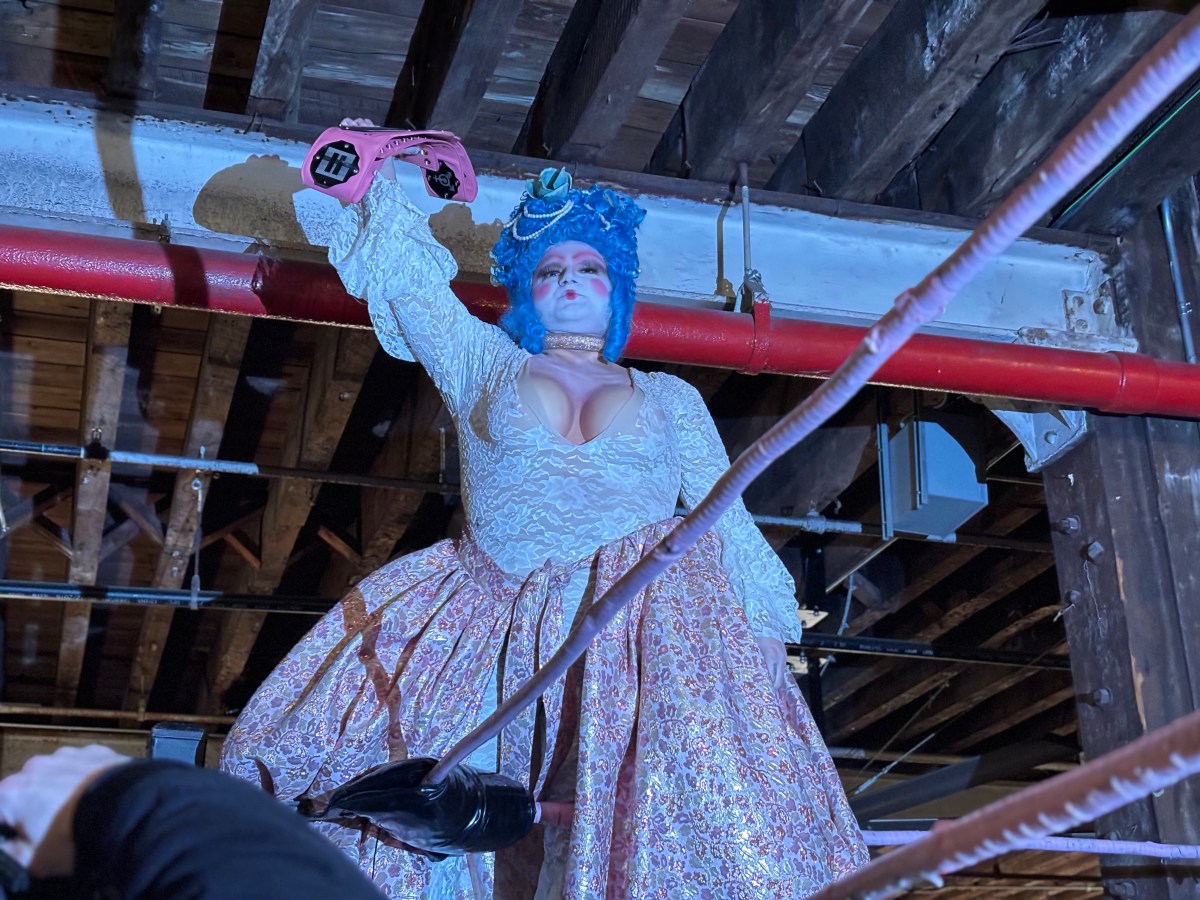

Ugandan lesbian and human rights activist Val Kalende. | INTERNATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION

About ten years ago, when I first came out to my guardian and, later, to my closest colleagues at the Daily Monitor newspaper in Uganda, I was nothing short of terrified of losing both family and friends.

As I had anticipated, declaring my love for fellow women got me my own share of homelessness, verbal abuse, and alienation, even from people I trusted the most. Abandoned as a teenager and forced into maturity at a tender age, I always believed in the transformative power of truth, because the truth, as they say, sets us free. My “coming out” story as a Pentecostal-raised Ugandan lesbian woman is no different from the story of the activists who marched at the first-ever LGBT Pride parade in Uganda on August 4.

When I learned that my colleagues were organizing Pride, I was more concerned about what Pride means to us as Africans than replicating what we have witnessed at Pride parades elsewhere. When I saw my colleagues marching on a muddy road, some walking barefoot with the national flag held high, not only was I reminded of our Africanness, but I felt close to home. And then I thought of our fallen comrade David Kato, who has constantly been on my mind since I saw the film “Call Me Kuchu” and whose life was cut short before we could experience this moment. I got teary.

I believe the concept of Pride anywhere it is celebrated is not just a moment, it is a precursor for change. I believe that like the 1963 March on Washington in the United States, which sparked a revolution that sent ripples of change as far as Africa, what happened in Uganda a few days ago will change the politics of local organizing among LGBT movements in Africa.

At the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC), I research how African LGBT movements organize and how international NGOs such as IGLHRC can support their work. In every country there's a unique strategy for organizing that is directly related to how each movement started. In Uganda, organizing an LGBT movement was partly prompted by President Yoweri Museveni's denial that there were any LGBT people in Uganda.

On a recent visit home I made a statement I knew wasn't going to get me too many friends, even among fellow activists. I said our struggle must move away from the victimization narrative and begin to focus on positive stories. It doesn't help us when foreign journalists, bloggers, and allies present our struggle as “desperate” and come to Uganda simply to write about what is wrong with our country while ignoring our success stories.

While the “ desperate” narrative puts us in the international spotlight and does hold our leaders accountable, it also pits us against our fellow nationals. A balance of both narratives will bring the change we all need. I have been involved with LGBT community organizing in Uganda long enough to observe how far we have come and what we have managed to achieve amidst very difficult circumstances.

For instance, there was a time when Ugandan LGBT activist and Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) founder Victor Mukasa was the lone visible face of our struggle. It is because activists like Mukasa tirelessly knocked on the doors of consular offices –– even if those doors sometimes didn't open –– that U.S. and other world leaders care about LGBT people outside their borders. Today, world leaders like Ban Ki-moon and Hillary Clinton listen and are committed to taking action.

On balancing both the negative and positive, it is important that we acknowledge that the first Uganda Pride was a success and at the same time condemn state-sponsored harassment of LGBT activists. Three transgender women and professional dancers, while running away from the scene after police raided the event, were handcuffed, arrested, and harassed. One transgender woman, Beyonde, was reportedly beaten by a policeman for resisting arrest.

It has become a trend for Ugandan police to arrest, harass, humiliate, and in some cases shoot at unarmed civilians. Two months ago, a video of an armed and uniformed policeman half-undressing and squeezing the breast of a prominent female politician was making the rounds on the Internet. Police anywhere in the world are mandated to enforce the law, not to break it. In my country, they are breaking it.

State security officials have unlawfully raided three LGBT gatherings in the past six months. While the Anti-Homosexuality Bill is still being debated for passage, it should be made clear that it is still proposed legislation. Enforcing a not-yet-passed bill as law is not only unlawful, it is a gross violation of human rights.

Similarly, the growing trend of labeling any gathering of LGBT people a “gay wedding” is an affront to human rights and a red herring informed by utter ignorance and speculative fear of the unknown. While religious fundamentalists in the West are now clutching at straws as laws against same-sex marriage are repealed, they are exporting their homophobic values to Africa.

We have learned enough from Christian missionaries, such as Holocaust revisionist Scott Lively, to know that when Western conservative narratives are exported to Africa, African politicians see an opportunity to further criminalize same-sex persons. As we proudly and loudly showed up at the Beach Pride parade last week at the Botanical Gardens in Entebbe, we were simply demanding our right to peaceful assembly, expression, and association –– the same rights enjoyed by all other Ugandan citizens.

Val Kalende is a fellow at the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission and a doctoral student at the University of British Columbia.