In her memoir, Martha Shelley, then a member of the New York City chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis, recalls escorting two lesbians from Boston who were interested in establishing a chapter of that early lesbian group in Boston on a tour of the West Village. They came across a crowd of mostly men who were battling the police on Christopher Street on a June night in 1969. Shelley assured the visitors that rioting was common in the city.

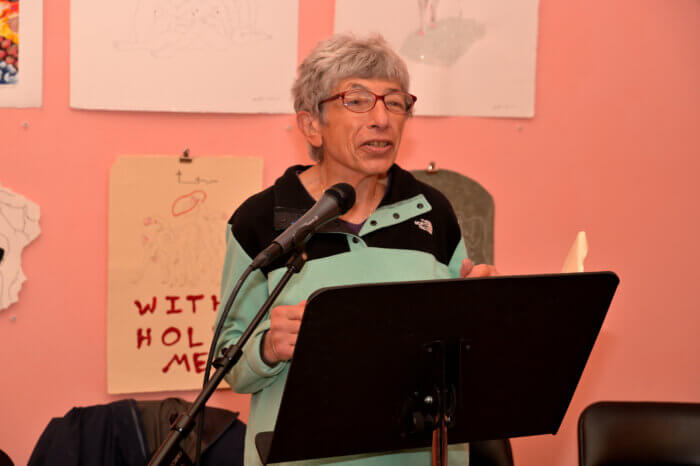

“I had no idea that Saturday night that I was witnessing an event of tremendous significance,” Shelley said during an Oct. 15 reading of “We Set the Night on Fire: Igniting the Gay Revolution,” her memoir, held at the Bureau of General Services – Queer Division, a bookstore that is housed in The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center in Manhattan.

That rioting, better known as the Stonewall riots, marked the start of the modern LGBTQ rights movement or, as other speakers said, those riots were the moment that launched a movement. Shelley was joined by five other speakers who, like Shelley, joined the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), a radical LGBTQ group that was founded less than a month after the riots and whose members would be very important in building the broader community.

“We were a raggedy ass bunch of kids,” Shelley said. “We had no money, but we changed the world.”

Shelley and Marty Robinson, also a GLF member, produced the July 1969 rally that responded to the riots. It drew an estimated 400 people to Washington Square Park, according to police reports made at the time. While there had been pickets and protests by members of the LGBTQ community in New York City previously, they were typically small events drawing a handful of people. The best known protests were the Annual Reminder Days that took place every July 4 near Independence Hall in Philadelphia from 1965 to 1969. Those protests had strict behavior and dress codes requiring women to wear skirts and men to be clean shaven and dress in suits with white shirts and ties. The Annual Reminder Days typically had several dozen picketers.

While LGBTQ groups had been expressing the hope for a national movement since at least 1965, that did not emerge until after the Stonewall riots when GLF chapters, Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) chapters, and other LGBTQ groups sprang up across the nation and in other nations in the West. Like the first GLF chapter, those organizations were often founded by activists who had honed their organizing skills in the anti-war movement, the civil rights movement, the women’s movement; in radical groups, such as the Students for a Democratic Society; and other groups that were part of the New Left.

“We took all the advances the women’s movement, the civil rights movement made,” said Perry Brass, an author and longtime LGBTQ activist, at the event. “That gave us a theoretical basis.”

Joining Brass and Shelley as speakers were John Knoebel, Mark Horn, Flavia Rando, and Mark Segal, all former GLF members and current board members at Gay Liberation Front Foundation, a group that is dedicated to preserving GLF’s history. Ellen Broidy, who, among other achievements, is credited with organizing the 1970 march that commemorated the Stonewall riots with Craig Rodwell, Linda Rhodes, and Fred Sargeant, is also a GLFF board member, but did not attend the Oct. 15 event. That march drew thousands of participants. Activists Michael Brown, Marty Nixon, Marty Robinson, and Foster Gunnison, who was not a radical, also contributed.

That now Pride Parade, which has been celebrated annually since 1970, took its first steps toward becoming what is now a global event during the November 1969 meeting of the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (ERCHO) in Philadelphia when attendees, which included GLF members, passed a proposal to replace the Annual Reminder Days with a march on the last Saturday in June to commemorate the Stonewall riots. The GLF arguments were a mix of haranguing and polite persuasion. In a later report on the meeting, Gunnison, who attended that meeting, named one GLF member “Vinegar” and a second “Sugar” to describe their roles at the meeting. Frank Kameny, the founder of the Mattachine Society of Washington, DC and the Annual Reminder Days, presided over that meeting.

“Pride is probably the most important export that this community has given the world,” said Segal at the event.

That ERCHO meeting was just the start of the more aggressive politics of GLF and later GAA. GLF was the first LGBTQ organization to use Gay in its name. The Gay Liberation Front name very deliberately borrowed from the National Liberation Front of North Vietnam, which was battling the US in the American war in Vietnam.

GLF organized some powerful protests against police harassment and violence with what was effectively the second violent confrontation with police since Stonewall. That march began in Times Square and ended in the West Village, where “[D]isturbances occurred such as bottle throwing cars being overturned and harassment to the police detail on hand by demonstrators and spectators. As a result of this approx. 10-13 arrests were affected,” according to a police report made at the time.

But the group did more than this. GLF and GAA chapters dominated the first and only meeting of the National Coalition of Gay Organizations (NCGO), which was comprised of 85 groups from 18 states, that met in Chicago in 1972 to develop a list of demands that were eventually presented to delegates at the Republican and Democratic conventions that year. Among the NCGO demands were the right to marry, though they opposed restrictions on the number of people who could enter into one marriage, and an end to discrimination based on sexual orientation in military service.

The foundation was launched not only to preserve GLF’s history, but also to counter untruths about GLF, such as the group only lasted six months, it was “so contentious and everyone just hated each other,” and “GLF did nothing,” Brass said.

“The entire modern gay movement came out of GLF,” Brass said. GLF lasted for three years, but its members would go on to build community institutions, such as what is now the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, the center where the Oct. 25 event was held, and “many, many institutions that radical lesbians set up,” Rando said.

“You can think of us as the Big Bang,” Knoebel said.

“We Set the Night on Fire: Igniting the Gay Revolution” | By Martha Shelley | Chicago Review Press | $28.99 cloth; $14.99 PDF or e-book | 224 pages