It’s spring, yet most of us are stuck inside, groping for a positive attitude while hoping we’re negative for the coronavirus. Here, in the apartment where I shelter with my partner, Laura Whitehorn, there is constant turmoil.

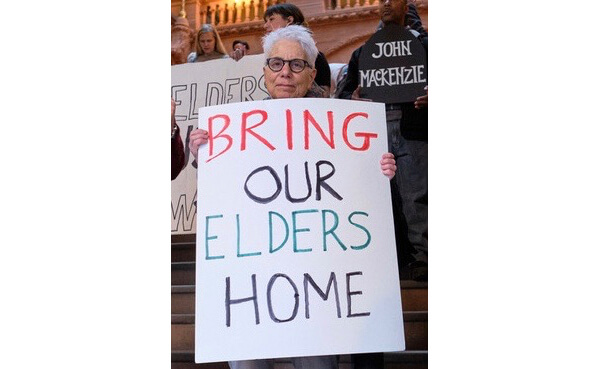

Laura, who spent over 14 years in federal prison, helped found Release Aging People in Prison/ RAPP. Currently, Laura has been going nuts, blasting every shred of her already shredded being into getting Governor Andrew Cuomo — or anyone with enough power — to release elders and other vulnerable people in state prisons before COVID-19 inevitably swamps those facilities. Coronavirus news changes every second, but, at the moment I’m writing, New York City has released 23 older people from city jails — less than one percent of all incarcerated adults in the state.

I fully support and admire Laura’s efforts, but hey, it’s been weeks since we’ve had one conversation without Laura defiling our “quality time” to answer a text or make some urgent phone call, hoping to get elders released. Frankly, I would like to depressurize this political pressure cooker. That’s why I’m sharing it with you. Here is an interview with my life’s helpmate, in hopes that it will do us all some good.

[I get my iPhone and sit Laura down on the couch.]

SUSIE DAY: Why are you — and RAPP — throwing everything you’ve got into getting elders out of prison — and driving us both crazy?

LAURIE WHITEHORN: I started RAPP with two other, formerly incarcerated people, all in our late 60s, early 70s. Two of us had spent years in New York State prisons; I was in the federal system. We were all inside in the 1980s and ‘90s, during the AIDS epidemic. And we were horrified, seeing friends around us suffering, dying, ostracized. There was no treatment, no care. So, from our different prisons — we weren’t in touch with each other — we all started peer education programs. We understood the connection between public health and the incarceration of people who are growing older and older, who the system will not release.

I live — you know this — with grief for the people I watched die in prison. There wasn’t even an HIV test then. Women would be taken out to the hospital, come back. They’d say, “I have a new kind of pneumonia, I’m gonna die, and I have AIDS – I don’t know what that is.” No one on the street was saying that women get AIDS then, we were just seen as vectors for men to acquire it.

In our kitchen, by the coffee canister, as you know, there’s a photo of Joyce, who died in prison with AIDS. She was my best friend inside; she didn’t tell anybody she was sick, I guess because being Black was already hard enough. All of us who’ve done time are haunted by those beloved friends, who died inside because there was no care — the system just wasn’t capable of it.

This time, it’s not a sexually- and blood-transmitted pathogen; it’s one you can get from just being in the same room with someone who’s shedding virus droplets, or it’s on exposed surfaces.

DAY: How many elders are there now in New York State prisons?

WHITEHORN: About ten thousand; 10,239. That’s people in the state system over 50 — not counting younger people at risk with underlying conditions.

We started RAPP in 2013 because we saw that the proportion of older people in New York prisons had doubled, while the overall prison population fell by almost 30 percent. This was because most reforms apply only to people with so-called low-level, nonviolent offenses. But years of “lock-’em-up” media and politicians making their careers off convincing the public that crime is America’s number one problem have given us thousands more people in prison with impossible sentences like life without parole.

These are people — mostly Black and Brown — who are growing old, who will become ill, as the virus infiltrates the prisons, which it’s beginning to do. They’re usually convicted of violent crimes. We’re all trying to minimize violence, but people with those sentences have the lowest risk of recidivism, once they reach about the age of 50. They’re the people who are being denied release over and over again.

If you give someone at age 19 a 25-to-life sentence, and then hold them way past their 25-year minimum, they’ll likely die in prison. They can’t change what they did when they were 19; all they can do is transform themselves into a new person. But that person becomes invisible if you permanently brand them with their original crime. These are people in danger – that’s why you see how nuts I am. There’s an urgent need to get people out — it’s an emergency.

DAY: What about people like me who’ve never been to prison? Why should I care who gets out when I’ve got my own coronavirus worries?

WHITEHORN: Because we can’t let social distancing become moral distancing. We can’t live in a society that kills people, where people only care about themselves.

I’m 74 and — you know, you live with me — I’m nervous. I have underlying conditions. But what keeps me up at night is, “What does shelter in place mean if you’re homeless? Or if you’re in prison, where you’re almost sure to be infected?” We’re getting chilling messages from people inside: no cleaning supplies, no TP, no soap, no attempt to screen corrections officers, who bring in COVID-19. We have to understand that the social distancing strategy implemented outside is utterly impossible inside overcrowded prisons. I remember when I lived in a cell built for one person — it actually housed four. The death penalty was outlawed in New York State because people here are against inhumane punishment. But this is a new death penalty.

DAY: Are you having any success?

WHITEHORN: You see me run to my computer every five minutes to put another article on the RAPP website. Even Fox News is arguing people should be released, as are former prosecutors, current prosecutors. The heads of the Corrections Committees in the State Senate and the Assembly have a proposal for letting out people a couple of years within their release date, or anyone who’s parole-eligible and has already hit their minimum sentence.

The reason I think we’re not seeing action by the governor of New York is that he’s getting pressure from the police. The police and the guards union wield enormous clout, so this is becoming a political issue. Governor Cuomo: do you really want to get your public health and human rights agenda from the police?

Cuomo puts himself forward as a progressive — on some issues, he’s pretty good — but on the criminal legal system, he’s afraid of blowback from the people who created this incarceration crisis in the first place by pushing a law-and-order agenda. He’s on TV, talking about risk factors. He issued Matilda’s Law, basically grounding his own mother and others like me over 70 — we can’t go out of the house. Cuomo sees his mother — and by extension, others of us — as human beings. But he’s forcing people in prison to shelter in place, exactly where they’re most endangered. So can you imagine, if Cuomo doesn’t act and people inside are left to die, how he will be remembered? We can’t call this inaction: he’s acting by not letting them out.

DAY: Is releasing people only up to Cuomo?

WHITEHORN: No, but he’s number one. He has the power to cut through red tape on a dime, issue an executive order: Clemency to every person over 55, or with an underlying condition. The Parole Board could also immediately release people. The Legislature could craft something. But the people who have the most power, who could do the most good, are silent. And if Cuomo doesn’t do this, then really, he’s on a par with Trump, who believes there are two kinds of people: his people, and those he calls animals, criminals.

DAY: Can people on the outside help?

WHITEHORN: Everyone can do something, use whatever position they have in society to demand Cuomo and the Parole Board release people in the New York State system. They can go on RAPPcampaign.com and look at the petitions, the letters, join the Twitter campaigns. We have virtual forums about this. RAPP supports two legislative bills with a lot of co-sponsors, which look even more rational and important in light of this virus. To help release immigrants in detention centers, they can go to JusticeRoadmapny.org. People should educate themselves, write letters to their local papers, organize their social circles. Everyone has some power —

Oh Jesus, I’m getting a migraine [stands up, holds forehead]. I can’t believe this…

DAY: Just tell me why do you keep doing this when it’s making your head throb and turning our home into Nerve Central?

WHITEHORN: [Long pause] How could I not? If I was in prison now, I would want someone to fight for me. It hurts my heart to imagine sitting here at home, watching TV — doing more cooking than I’ve done in a year because we can’t go out — and looking at that picture of Joyce.

The thing is, this is such an easy fix. Prisons don’t stop violence, but even if you think they do, there’s no reason for people with zero risk of committing another crime to be held there, waiting to get sick. The fact that quote progressive institutions in this state are enacting inhumane policies — which are racist in the deepest way — when they could do something different, that’s something I cannot sit with.