Over five decades, unsurprisingly, myths have grown up around the six nights in 1969 when what we now call the LGBTQ community rose up in opposition to a police raid on the Stonewall Inn. There was a period of time when a favorite story was that gay people stood up to the police because of Judy Garland’s death days before and that the Stonewall Uprising’s success was all due to “drag queens.”

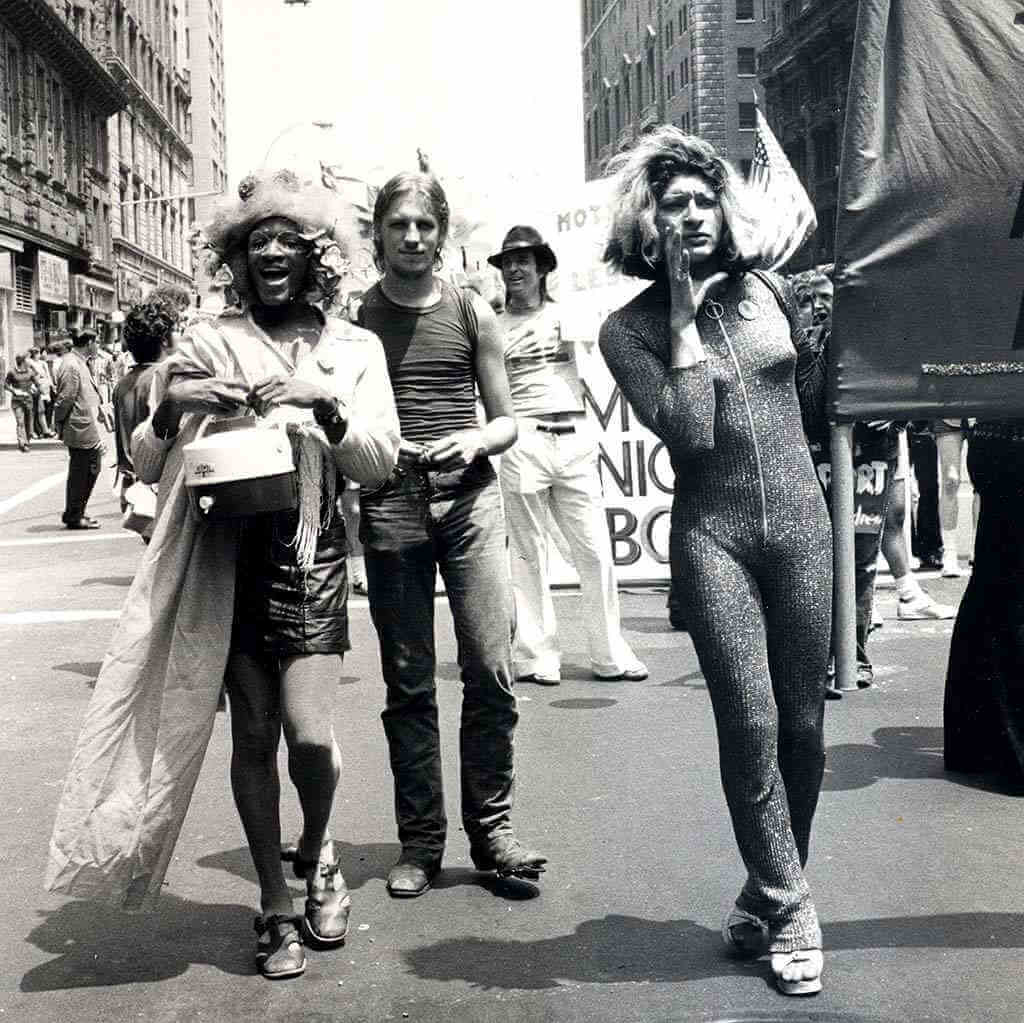

In the last few years, there has been increased interest in the role of transgender women and black and Latinx folks in the Uprising, a focus that has sparked complaints that white gay men have stolen the credit from those who did all the heavy lifting on that fateful first night.

A colleague of mine who shares my interest in the history of Stonewall said the tendency to “brand” the event as the work of one group or another threatens to irretrievably bury the known facts about a complex event unprecedented in New York’s LGBTQ history. In the spirit of respecting history and the preservation of facts that we are able to establish, I will draw on the years of research that went into my 2004 book, “Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution,” to examine the roles of specific individuals who have been in the spotlight in recent discussions and more generally explore what we know about the demographics and backgrounds of the crowd that exploded on that June night half a century ago.

Marsha P. Johnson: There is strong evidence, backed by several independent accounts, that Marsha P. Johnson — one of two transgender women who will soon be honored with a city monument in Stonewall’s vicinity — was among the first people to push back violently against the NYPD in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969. An important part of that evidence comes from John Goodman, whose presence on that first night of the Uprising is not in doubt. Jerry Hoose told me that it was Goodman who phoned him to summon him to Christopher Street. Robert Bryan, a very close friend of Goodman’s, said he was there with Goodman that first night. When Hoose arrived at the scene, Goodman told him that Jackie Hormona, a homeless gay street youth, “had kicked a cop, maybe, or punched a cop and then threw something through the window, and then everybody got going. But he [Goodman] was there and he attributed it to Jackie… And all the other queens like Zazu Nova Queen of Sex and Marsha P. Johnson had got involved.”

Bob Heide, who knew Johnson before the Uprising, told me he saw her there on the first night — “just in the middle of the whole thing, screaming and yelling and throwing rocks and — almost like Molly Pitcher in the Revolution.” Some weeks after the Uprising, Heide heard that Marsha was the “first person to start throwing bottles.”

Sylvia Rivera: Sylvia Rivera — the other trans woman to be honored with Johnson in the city’s planned monument — was a fellow activist with Johnson and her name has been linked to Johnson in the public mind regarding the Stonewall Uprising. Rivera, who died in 2002, long claimed to have played a leading role in starting the Uprising, making a point of saying she headed to the Village that night to meet Johnson because June 27 was Johnson’s birthday.

A quarter of a century of research on Stonewall’s history has convinced me that there is no credible evidence that Rivera was there on that first night. On the contrary, I have found a large body of evidence that she was not — starting with the fact that Johnson’s birthday was actually in August.

The important evidence, however, came from Marsha P. Johnson herself. When Johnson spoke to Eric Marcus for his 1992 oral history book, “Making Gay History,” she said that at the time of the Uprising Sylvia was uptown in a park. “The way I winded up being at Stonewall that night, I was having a party uptown,” Johnson told Marcus. “And we were all out there and Miss Sylvia Rivera and them were over in the park having a cocktail. I was uptown and I didn’t get downtown until about two o’clock.”

There are several other statements Johnson made to highly credible witnesses — namely, Randy Wicker, Bob Kohler, and Doric Wilson, all with deep and enduring ties to the LGBTQ rights movement — about Rivera not having been at the Uprising.

In notes from a 1998 interview with Kohler, I wrote, “After we’d been talking a while [Kohler] looked at me and said that Sylvia Rivera was not at the riots and arrived downtown on the scene only two weeks later. He explained later in the conversation that Sylvia always hung out in Bryant Park uptown. He told me that Marsha would sometimes correct Sylvia on this, saying ‘Sylvia, you know you weren’t there.’”

Significantly, even though Kohler told me Rivera was not at the Uprising, he made it clear he hoped I would portray her in my book as having been there. Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt told me that he and Kohler had discussed why he would say Rivera was there even though he knew that she was not. Lanigan-Schmidt said that Kohler told him he felt it was important so that young Puerto Rican transgender people on the street would have a role model.

Kohler, in fact, recounted a discussion he had with Rivera when he agreed to back up her claims — at least to a limited extent. His recollection went like this:

Rivera: Bob, will you back me on my having thrown the first Molotov cocktail?

Kohler: Sylvia, you didn’t throw a Molotov cocktail!

Rivera: Will you back me on my having thrown the first brick?

Kohler: Sylvia, you didn’t throw a brick.

Rivera: Will you back me on my having thrown the first bottle?

Kohler: I will back you on having thrown a bottle.

Randy Wicker confirmed to me what Kohler said he had heard from Johnson. My notes on a 1998 conversation with Wicker reads, “He told me about Sylvia not being at Stonewall… Randy remembered Marsha P. Johnson telling him that Sylvia was not at Stonewall at the beginning of the night but later, as she was asleep after taking heroin uptown.”

Doric Wilson, the theater legend and gay rights activist, told me of a conversation he witnessed shortly after Rivera had forced her way onto the rally stage during Pride in 1973. After famously haranguing the crowd, Rivera exited the stage and was going on about having been at Stonewall, when Marsha looked at Sylvia and said, “You know you weren’t there.” Wilson said that Rivera just became quiet at that point.

The credibility of Rivera’s claim to have been at Stonewall was also called into question by the inconsistencies in her own accounts. In one interview, she said the night of the Uprising was the first time she had ever gone to Stonewall, while on another occasion she said she had been there before. One of her accounts had her wearing female attire the night of the Uprising, while in another interview she said she wore male clothing.

But it’s in Rivera’s explanation of why she became so violent at the Uprising that we find perhaps the most telling inconsistency. She told David Isay, “I had already done the Viet Nam, the civil rights, the women’s movement… fighting for everyone else, and here’s your chance… When the first bottle went by, it was, ‘Me, oh Lord Jesus, the revolution is here, hallelujah.” Rivera offered Marcus much the same account, saying, “Before gay rights, before the Stonewall, I was involved in the Black Liberation movement, the peace movement… My revolutionary blood was going back then.”

But before she became famous as someone believed to have been on the front lines of the Uprising, Rivera offered a very different perspective on her activism. In a 1970 issue of the newspaper Gay Power, Arthur Bell profiled Rivera after she had been arrested on 42nd Street for circulating a Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) petition. As Rivera told Bell her life’s story, she never mentions Stonewall nor any activism before 1970. Rather the story is of a sad life, made even sadder when in early 1970 her lover leaves her, sending Rivera to “the bottom of the hill.”

Then, Rivera said, she learned of GAA’s existence, went to their meetings, and “liked what he [sic] heard. GAA became the big thing in his [sic] life… filling a void… giving Ray [sic] a reason for being.” Decades later, Rivera would tell interviewers about sitting around with other gay and trans people dreaming about a day when they could be free and that Stonewall was that long-dreamed of day of liberation. But in a written note from Rivera at the conclusion of Bell’s 1970 article, she wrote, “Well, girls, many of us were waiting for a group like GAA. I knew many of us when we used to talk about the day we could get together with other Gays and be heard and ask for our freedom and our rights. Well, sisters, the time and days are here and Gay Activists Alliance is here to stay.”

The evidence, when looked at as a whole, suggests that Rivera was not at the Uprising but became involved with GAA in early 1970, as the beginning of a long career of activism. Over time, as she came to appreciate how celebrated an event Stonewall was and how much credit her friend Marsha P. Johnson received for setting everything off, Rivera began to say that she too had been there, tying her account to the already existing narrative about Johnson, who had woken her up on the first night of the Uprising to tell her about it.

Rivera’s activism after Stonewall on behalf of transgender people and homeless youth deserves the community’s respect, but on the question of Stonewall, I share the view of historian Martin Duberman, who told me he found her “wildly unreliable.”

Stormé DeLarverie: During my years of research, I worked hard to determine the reliability of the story of a lesbian fighting with cops on the sidewalk as the tipping point for the Uprising — and concluded it was true. The people who described the incident to me all gave matching descriptions of her appearance.

The established facts are these: a lesbian in male clothing who was being taken in handcuffs from the Stonewall club to a patrol car fought the police as they handled her roughly. After she was placed in the patrol car, she escaped and was caught again and put back in the patrol car. She escaped a second time, and either she or another lesbian shouted, “Why don’t you guys do something?,” before the police heaved her back into the car. At that point, the crowed exploded with anger, throwing objects at the cops. The witnesses I spoke to all described her as being tall, “beefy,” with a “bigger, huskier build,” in her 20s or 30s, and Caucasian.

Like Rivera, DeLarverie was inconsistent in her accounts of the Uprising’s first night. In June 1997, she stated she was outside the bar, being “quiet, I didn’t say a word to anybody, I was just trying to see what was happening,” when a policeman, without provocation, hit her in the eye. Later, at a panel discussion, she said that a policeman attacked her without warning from behind and that she then hit him, breaking his jaw so that it had to be wired.

The established facts of the lesbian who resisted arrest, however, have the altercation between her and the police beginning inside the club, where her hands were cuffed. There is no record of her having injured a police officer. But DeLarverie — who had an African-American mother and a white father, was of average height and build, and was 48 in 1969 — has her fight with the police beginning on the sidewalk when she was not cuffed. The only recorded head injury to a police officer that first night was an eye injury to Gil Weissman.

My research concluded that DeLarverie could not have been the lesbian whose resistance to the cops helped set off the Uprising.

The Crowd at Stonewall that First Night: In interviews with people present the first night of the Uprising or who were otherwise regular patrons of the Stonewall at the time, descriptions of the crowd were quite consistent. The club rarely had women customers — maybe one or two a night — and similarly did not pull a regular transgender clientele. The typical customers were young white males, though Stonewall drew some black and Latinx visitors as well, plus some men over 30.

Once the Uprising began, the crowd on the street outside the Stonewall pulled in many more passersby than could possibly have been inside at the time of the raid. Estimates of the crowd size range from around 400 when customers first spilled out of the bar to between 1,500 and 2,000 once the riot police arrived. The West Village in 1969 was much whiter than it would be later, and from interviews with witnesses I concluded that the crowd on Christopher Street that night was largely young, white, and male.

Some key witnesses on this point lend a good deal of credibility to this conclusion given either their own ethnicity or their track record of sensitivity on questions of race and ethnicity: Dawn Hampton, a black woman who worked at the Stonewall interviewed by Eric Marcus; Raymond Castro, a Puerto Rican man who fought with police on the first night and the only gay man that we can document from police records as having been arrested on the first night; Bob Kohler, who worked with the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), traveled to the South to protest segregation, and, as a talent agent, worked with black actors to get them cast in non-stereotypical roles; and John O’Brien, a Marxist and a founder of the Gay Liberation Front, who told me he also went to the South as a civil rights activist and came back with a scar from police dogs.

Hampton stated the club’s customers were “mixed Spanish, whites, and blacks, but there were more whites than the others.” Castro said that the group of three “drag queens,” bar staff members, and one lesbian put in the patrol wagon with him all were non-Latinx whites. Kohler said he remembered the “drag” people he saw being put in a patrol wagon as white. O’Brien recalled that the people he fought the police with were largely white, with a few Puerto Ricans.

My conclusion is that most of the crowd in the vanguard on the Uprising’s first night were white men, though Marsha P. Johnson and Zazu Nova, both transgender, were black, and there were some black and Latinx youth among the homeless street youth who were the first to lead the charge against the police. Several Latinx men were also among the first to resist or attack the police. A Puerto Rican man named Gino threw one of the first big objects outside the club, uprooting a large stone from the pit of a tree. Castro’s fight with the police — shortly after the cops finally subdued the struggling lesbian — was not only ferocious but apparently further fueled the crowd’s anger initially sparked by the mistreatment of the lesbian.

Kevin Dunn recalled that after the police had retreated from the angry crowd into the club, he picked up “a carton — and I was just about ready to throw it, but I stopped and said, ‘But you’re not supposed to be violent, you’re against violence.’” As he hesitated, “a big, hunky, nice-looking Puerto Rican guy — but big mouth — yelling out next to me… took that thing out of my hand and threw it! And it was one of the first things that got thrown at the Stonewall.”

Bruce Voeller, who went on to become an important activist in GAA — and later in what is now the National LGBTQ Task Force — wrote that soon after the police allowed those they were not arresting to leave the club, “A crowd gathered and some of the watchers jeered the police. After a few interchanges, a young Puerto Rican taunted the gays, asking why they put up with being shoved around by cops.” Voeller wrote that according to some accounts, it was this same young man who hurled a beer can that led the crowd to unleash a barrage of objects aimed at the police.

My research concluded that the two most important groups in the vanguard on the first night — beyond the butch lesbian who resisted arrest and probably had the greatest impact — were homeless gay street youth and transgender people, including Marsha P. Johnson and Zazu Nova, both trans women, and Jackie Hormona, a member of the gay street youth. Most of the gay street youth were more or less feminine — or, in today’s parlance, non-gender conforming — young men, not transgender, and the majority were white.

While this vanguard played the key role in escalating the conflict, it is important to not let their pride of place throw others who fought into the shadows. When I recently mentioned the two groups in the vanguard to Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt, he said, “But almost immediately — within a few moments — everyone else was jumping in.”

In the end, does it matter whether individuals or groups get too much or too little credit? I think it does matter for a variety of reasons.

First, many people were injured during the Uprising and we know the names of almost none of them and never will. It seems a grave injustice to me for some people to take credit for playing a key role when they were not there while many who were injured will never be recognized.

Second, it has been always been difficult to get the history of our community recognized as legitimate. If we want the world to take it seriously, we simply can’t be willing to accept accounts as legitimate without evidence or that go against evidence available to us.

Third, if it did not matter, why would there be so much emotion expressed about which individuals or groups were present or in leading roles? No doubt, people of color and transgender people are concerned that their history be respected. But let us recall that people of color and transgender people did play important roles in this revolt. The challenge is in clarifying and documenting who they were.

Finally, I think it is worth noting that during the Uprising participants were not thinking in the neat categories we employ today — the community did not use the language that we use today and we risk being anachronistic by forcing people of yesteryear into today’s categories. My research convinces me that at the time of Stonewall, there was simply a feeling of our community standing up as one together to protect itself. Perhaps someday that feeling of oneness will return.