There’s always the best time to see a place. Sometimes though, that’s not when you get the chance.

So it was for me with a trip to Sydney, Australia this past July, months after the city hosted World Pride, coinciding with annual Mardi Gras. My last time here was another major LGBTQ+ gathering, the Sydney 2002 Gay Games, reusing sports facilities from the 2000 Millennium Summer Olympics.

What was Sydney like months after hosting the world’s biggest gay event?

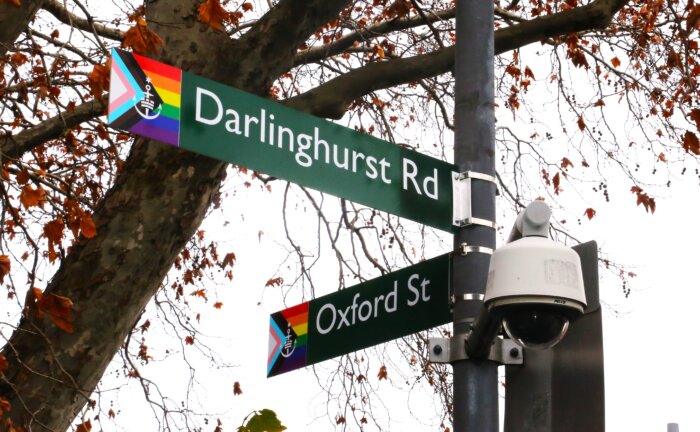

Don’t Worry, Darlinghurst

I stayed in Darlinghurst, the city’s main gay neighborhood. It’s a district full of exquisitely preserved Edwardian buildings — an architectural style known in Australia as Federation, honoring when the country officially became the Commonwealth of Australia on January 1, 1901.

The neighborhood revolves around Oxford Street, full of rainbow flags and remaining World Pride paraphernalia. Reigning over Taylor Square was a giant billboard of Margot Robbie as Barbie, and it was not until then that I realized she’s a native Australian. Seeing her each time I returned to the district, reclining in the classic 1959 black and white striped bathing suit, put a smile on my face. What gay boy doesn’t love Barbie?

Each element gave Darlinghurst a gay fairy tale atmosphere. Globally, gay neighborhoods are transforming, if not altogether disappearing, from gentrification and other forces, including ironically, LGBTQ+ rights advances. However, I was struck by Darlinghurst’s cohesive density of gay businesses, maybe denser than our own Greenwich Village.

A Neighborhood in Transition

Sydneysiders have found fault with this district, including its treatment by city government.

I would learn more from Lawrence Gibbons, the native New Yorker and publisher of Star Observer, a publication I have also written for. We met in the rooftop bar of the Colombian Hotel, its façade adorned with a banner commemorating his paper’s 45th anniversary. That time period also marked the anniversary of the ‘78ers, who were victims of a police raid considered to be Australia’s Stonewall moment. Our view encompassed Oxford’s northwestern side, a massive construction zone of gutted buildings, boarded up with whimsical murals celebrating gay Australian history. Lawrence also gave me an overview of why, despite my view that Darlinghurst was dense with thriving LGBTQ+ businesses, some gay Sydneysiders doubt the future.

One was decline from the Lockout Laws, passed in 2014 to reduce drunken violence and gay bashings, but which also decimated nightlife. By midnight, patrons had to stay in whatever bar they were in, making bar crawls impossible. These rules ended for Darlinghurst in January 2020, just in time for the COVID-19 pandemic. Combined with dating apps favored by young people and an expensive price tag, the risk of a potential downward spiral looms.

Lawrence also spoke of the mural-adorned barriers as a publicity buy-in for neighborhood gays to support the street’s transformation. It was also a quick patch to make the area presentable during World Pride, despite construction delays.

I had more questions, but Lawrence simply reminded me, “you can read all about it online at my paper.” Good advice for anyone Sydney-bound.

I returned to my hotel, the gay-friendly budget option Sydney Crecy, about $70 US dollars a night, one of the few businesses open in the construction zone. The view from my window was a gay fantasy: hunky construction workers with a backdrop of painted rainbow flags, as if they were filming a Village People video. Or an Only Fans. One more part of the fairy tale atmosphere ensuring, at least to me, that Darlinghurst was still Oz’s Emerald City.

Wonder Mama and Her Tour

It’s a dream of mine to meet Lynda Carter, so far a wish from my mouth to God’s ears. In the meantime, how about seeing Darlinghurst with a drag persona inspired by Wonder Woman? Sydney’s Fabulous Wonder Mama is a sight to behold, especially when I first saw her as I waited in Hyde Park, Mardi Gras’ traditional starting point. It’s also where she begins her unique tour which she first developed for Mardi Gras 2020, just before the world shut down.

Wonder Mama gave an overview of the district and Mardi Gras, Australia’s largest annual event, explaining, “Mardi Gras is the world’s biggest nighttime Pride Parade. It’s actually one of the very few nighttime Pride Parades.”

Mardi Gras’ early history explains the ‘78ers, when its first occurrence turned into an attack by the police. It began at Taylor Square along Oxford, a nighttime call for people to come out of the bars into the street. When police diverted the route, marchers “were met with all the paddy wagons, and that’s where the riot broke out,” Wonder Mama said.

She would tell me more details about the district’s history, explaining, “Oxford Street didn’t become the LGBT Center out of nowhere. It was actually thanks in part to this lady Dawn O’Donnell,” a woman who “built these amazing venues. And she loved drag.” I would learn more watching the documentary Croc-a-dyke Dundee, The Legend of Dawn O’Donnell, its title a play on Crocodile Dundee. Even the idea for The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert was born in her clubs.

Wonder Mama’s tour highlights venues like The Oxford Hotel, The Stonewall Hotel, Universal Bar and many others, along with Planet Dwellers Travel. We also stopped into the office of politician Alex Greenwich, whom she described as “an independent member of Parliament here. He’s an openly gay man himself, married to his husband Victor, who is quite cute.” Then, more seriously, she intoned, “There’s been a lot of hate crimes. We’ve had religious groups turning up and preaching on the streets, very antagonistically.”

She brought alive the historical murals, telling me at one panel that Bobby Goldsmith was one of the first people in Australia to die of HIV/AIDS complications. On another, she highlighted entertainment persona Courtney Act, a play on ‘Caught in the Act,’ who had been on RuPaul’s Drag Race.

That sense of gay serendipity and close ties was also apparent. We ran into Ken, owner of clothing store Aussie Boys, and a woman named Shane from another store testing whips and other toys. Ken told me of the curious construction workers who asked him to take them into one of the sex clubs, Bunker. A few blocks away, near The Bookshop Darlinghurst, we watched a man crawling in an alleyway in a leather fetish mask, another holding a smartphone in front of him. “That’s just the boys from Sax Fetish doing their social media,” Wonder Mama told me, before bidding me goodbye with a flash of her cape at the Sydney Rainbow Crossing on Bourke Street.

Darlinghurst. Magical indeed.

QTopia Sydney, the Queer Museum

The old police station and jail at Taylor Square, long ago a site of horrific LGBTQ+ oppression, will become the queer museum and art center QTopia Sydney. It’s a remarkable transformation, opening February 23, 2024, in time for Mardi Gras. This turn of the last century street scene is a step back in time and includes old public toilets, once a site of what locals called cottaging or gay cruising.

Until the grand opening, the temporary QTopia is a few blocks away in Green Park’s colorful kaleidoscope-windowed bandstand. Nearby are several important sites, including St. Vincent’s Hospital, which like its New York City name doppelganger was among the world’s most important hospitals treating people with HIV/AIDS. The Sydney Jewish Museum is nearby, and stories of Jewish and gay oppression meld at the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Holocaust Memorial, a giant pink glass triangle recalling the patches Nazis forced gay people to wear.

I toured the bandstand with Amber Vincent, who heads operations for QTopia. The circular space is jammed with exhibits, including one about two teenage boys accused of sodomy in the colonial era and left to die on separate islands. “We believe it’s the first documented hate crime really way back in the day, 1727,” Amber told me.

A striking snake mural tells “the story of the Rainbow Serpent across the indigenous culture,” Amber said about the piece made by local artists, part of ancient traditions relating to the finding of water holes, rather than a direct LGBTQ+ reference.

“Queer people have existed as long as people have existed, which is why in indigenous culture, it extends back to the Dreaming and the Dream Times as far as creationism,” she said, referring to how Aboriginals, the world’s longest existing society with over 60,000 years of isolated history before colonization, recount how the world was created and survival mechanisms for a forbidding climate. An emphasis on such art, traditions and connections across cultures will be key for QTopia when it officially opens.

Aboriginal and Queer Art

My Australia visit was during the lead up to the Aboriginal rights referendum The Voice. It seems unfathomable that such issues are still debated, but it was not until the 1960s that the original inhabitants began to gain a modicum of basic rights, including to attend university. The referendum would fail, a horrific example of placing the fate of oppressed minorities in majority hands.

Despite this, I felt a marked difference in awareness of Aboriginal issues versus 2002, when white Australians openly exhibited racism. Now, almost every event acknowledges the original inhabitants.

I explored some of these issues with Wayne Tunnicliffe, head curator, Australian Art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales who recently worked on Queering the Collection, highlighting art with a queer history in the museum’s collection.

Its main building is a grand neoclassical structure. The museum opened a new South Building, housing Aboriginal art. Wayne told me that previously, such art was displayed in the older building’s lower levels. “There’s much greater awareness of First Nations cultures and pulling it out to center,” he said.

Queer and Aboriginal identity intersected in the work of photographer Christian Thompson, whose father is of the Bidjara Aboriginal peoples. Wayne called him “a particularly interesting artist,” whose work addresses his multi-ethnic heritage — white, Aboriginal, Jewish and Asian. In one self-portrait, he appears to be drowning in foliage and flowers. “He’s used indigenous flowers in here and peonies from China, as well, and that’s him in a sense,” he said.

For me, and for those who joke Australia is Canada with palm trees, it is Aboriginal culture that makes the country unique, a distinctive if long suppressed aspect nowhere else in the world.

So Long Sydney

My too short Sydney trip came after a much longer visit to Melbourne, speaking at an academic conference on my research at Purdue University’s Hospitality and Tourism Management School.

On my last night in Sydney, I wandered the Royal Botanic Garden, glimpsing Sydney Opera House and Sydney Harbour Bridge. The latter I had explored in depth 21 years before, climbing over and kayaking under it, and dining in The Rocks neighborhood restaurants nearby.

I absorbed the tranquil waterfront view, thinking how the Opera House, celebrating its 50th anniversary in 2023, opened when I was in kindergarten, marking Sydney’s arrival. Its roof was meant to recall sail boats or sea shells. Recently, it was lit in rainbows for World Pride, and before that, images of Queen Elizabeth. I thought, too, of what it must have been like for the Aboriginals who lived here for tens of thousands of years before first contact and displacement.

I hoped too it would not again be 21 years before I returned to the magical Land Down Under.