To some ears, it might sound like a throwaway comment, at least not offensive in that way. But, when the model Beverly Johnson, 70, a doyenne of the fashion industry, heard it, her expression went from incredulity to shock to a pain that reduced her to tears. The comment, decades-old but still as rancid, had been expressed to the world-class fashion photographer Richard Avedon sometime in the 1960s by legendary Vogue editor-in-chief Diana Vreeland in reference to an aspiring model named Donyale Luna. “She’s extraordinary,” Avedon argued, to which Vreeland, by way of refusing to include Luna in one of Vogue’s most historic fashion spreads under her tenure, declared, “So was King Kong.”

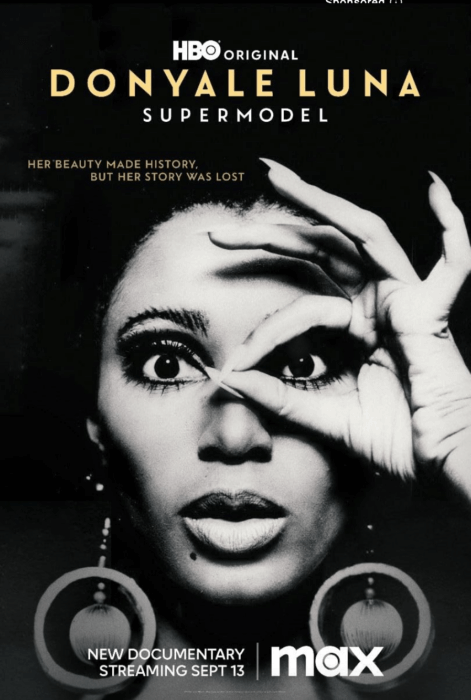

The scene is one of the most gripping in a new documentary, “Donyale Luna: Supermodel,” that recovers the discarded life of this African American model and actress who graced the cover of Vogue’s British edition, but was locked out of the American modeling industry, contributing to her psychological torture, drug overuse, and life cut short at age 33. Whether or not Diana Vreeland knew it, there is a longstanding racist trope into which her comment fell of likening Black people to apes. The fashion industry has to this day contributed its fair share of images to support that trope, from sending models down a runway in monkey ears and huge lips, to recreating a wartime propaganda poster of a threatening ape with LeBron James cast as the ape, to nicknaming late Vogue editor André Leon Talley, who was Black and presumably gay (and, as it happens, one of Vreeland’s own protégés), “Queen Kong.” Johnson wept, she tells the interviewer, from “an accumulation of all the pain.”

Peggy Ann Freeman was born in Detroit in 1945. Her rise and demise are a tale of nature versus nurture. The genetic lottery all of humanity is put through bestowed upon Freeman a long, elegant form, and racially ambiguous, though clearly non-white, facial features. To accentuate this arresting physical presence, Freeman cultivated an enigmatic mystique for herself, beginning with the adoption of the name Donyale Luna. At age 14, she was spotted on a Detroit street, clad in her school uniform, by New York-based British photographer David McCabe while on an assignment.

McCabe distinctly remembers Luna telling him that she looked the way she did because one of her parents was Mexican. It was a lie. In an America just on the lip of the civil rights era, Luna was aware that being “just a Black girl” would reduce her prospects, especially in an industry that sealed visage to value. She hence donned a cloak of ambiguity she’d wear for the rest of her life. Arriving in New York, she spoke with an accent that sounded more European than Midwestern.

Avedon took an immediate shine to her, purportedly to the point of obsession. He put her in a spread in Harper’s Bazaar magazine. The outrage that came from advertisers and subscribers over her appearance in the magazine halted Luna’s progression, and brought America’s One-Dropcracy into full focus. Her cloak of ambiguity in tatters, Luna decamped to Europe, never to reside in the US again.

Breakthrough opportunities in modeling and acting materialized for her in London, Paris, and Rome. In Italy, she marries and gives birth to a child, but spirals into despair, culminating in a drug-related death in 1979.

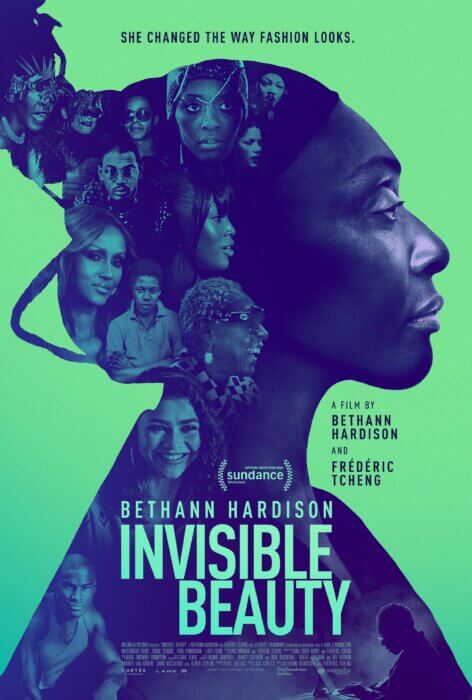

“Bethann Hardison: Invisible Beauty” can be seen as an uplifting sequel to the devastating ending of “Donyale Luna: Supermodel.” What a difference a decade can make! Hardison, now 80, emerged as a model in New York in the 1970s. She was discovered not by a gatekeeping white fashion insider, but an enterprising African American talent, the designer Willi Smith, who was hellbent on transforming American fashion with his “street couture.” Smith co-founded the ready-to-wear company, WilliWear, and was busy building its brand when he landed eyes on a boyish, short-haired Hardison striding confidently to and from her job as a salesperson in the garment district. He recruited her as his fitting model — a vocation she’d previously given little consideration — and her career as a runway and print model unfolded.

In 1984, Hardison founded her own modeling agency. Bethann Management represented a dazzling array of models of all races, both women and men, from Tyson Beckford to Veronica Webb.

Unlike Donyale Luna’s shroud of mystery and speculation, “Invisible Beauty” is a clear-eyed account of Hardison’s career through the lens of her own hindsight. It is, in fact, a palimpsest of the multiple attempts she’s made or is making to document the journey. First, she co-directed the documentary (with filmmaker Frédéric Tcheng). Second, one of its storylines is of Hardison working with an editor to write her memoir. And, finally, the film integrates footage Hardison previously shot for an unfinished documentary she’d begun years ago.

In 1988, with friend Iman, Hardison founded the Black Girls Coalition, a group comprised of Black supermodels combatting racially exclusionary practices in the modeling industry. In 2007, at one of the most whitewashed stages in modeling’s recent past, BGC, led by Hardison, held a press conference to release a data-rich report on the invisibility of models of color on the runways. Extensive footage from that forum is woven into “Invisible Beauty.”

At a post-screening talk at New York’s Film Forum last Sunday, an audience member asked Hardison if the modeling industry has “regressed, progressed, or stabilized” on visibility of models of color.

“I don’t know about stabilized,” Hardison answered. “But, it’s definitely progressed. Big up! Men, women, everyone. It’s diverse.”

“Donyale Luna: Supermodel” (1hr 34 min) is streaming on HBO. “Invisible Beauty” (1hr 15 min) is showing at Film Forum and opens nationwide on Sept. 22.

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is a professor of media sociology at The City University of New York – Lehman College.