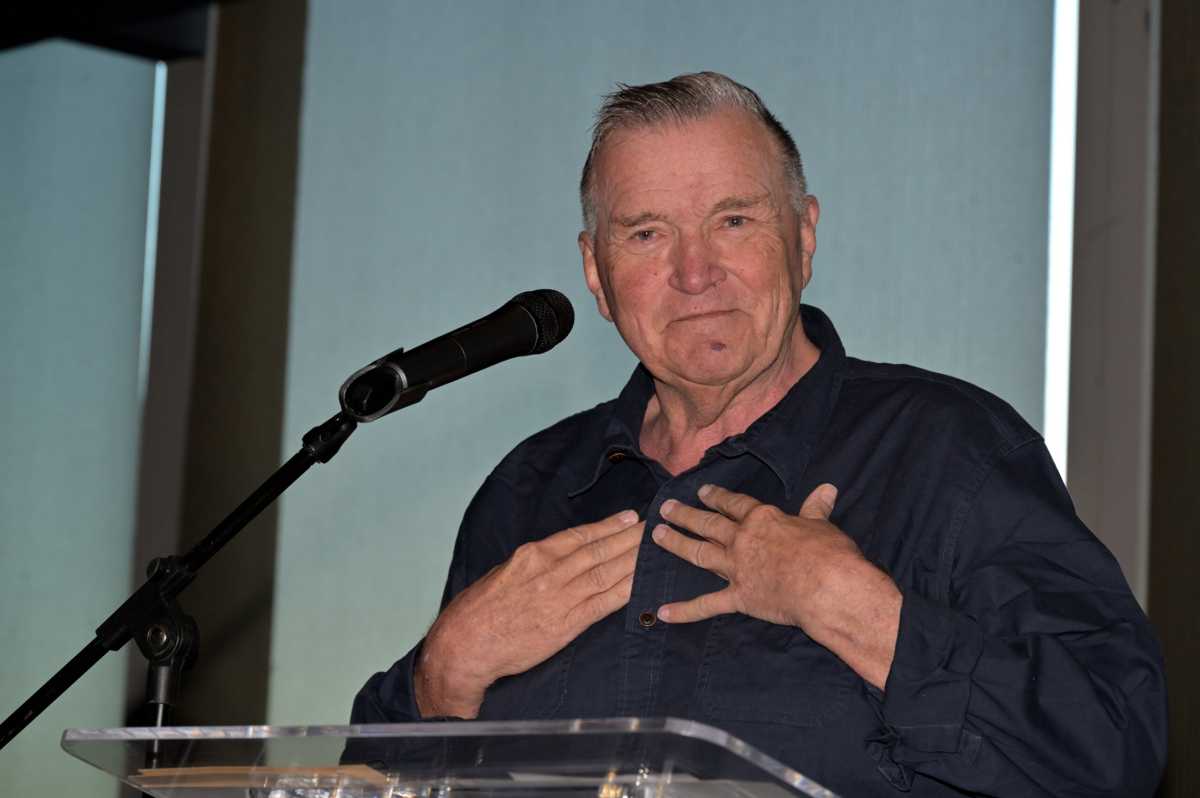

Hundreds of mourners filled New York City’s Church of St. Paul of the Apostle on March 25 to pay tribute to David Mixner, the gay political advisor and activist who shaped American politics for half a century.

More than 650 people watched the service that was livestreamed on YouTube.

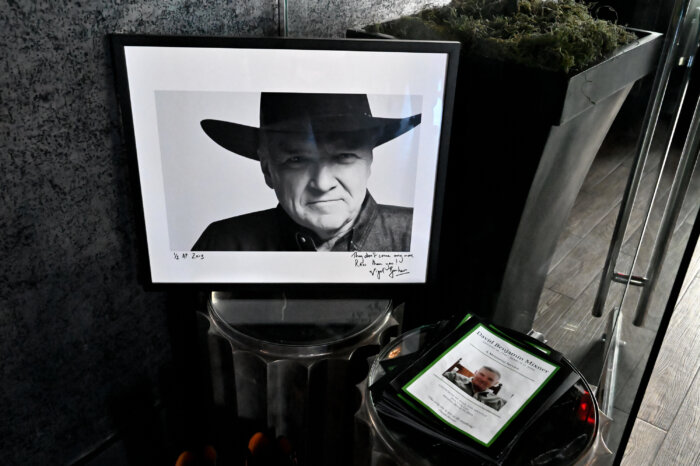

Mixner died at his Midtown Manhattan home on March 11, his friend and executor Steven Guy told the New York Times and the Washington Post. Mixner had complications of long-term Covid. He was 77.

For five decades, Mixner worked tirelessly behind the scenes to shape American politics and push for LGBTQ rights as a staunch, unwavering advocate, according to many LGBTQ political leaders who remembered the political advisor and leader in the civil rights, gay rights, and HIV/AIDS rights movements.

Starting at the dawn of the 1960s, Mixner participated in key historical moments, from presidential campaigns to the major movements of the time. He then became one of the leading forces in the LGBTQ rights movement in the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century.

Mixner was instrumental in co-founding powerful LGBTQ political organizations that worked to elect openly LGBTQ candidates to office, mentored future political leaders, and spearheaded major LGBTQ rights demonstrations. He chronicled his work in his memoir, plays, and many interviews in the media during his five decades of activism and political engineering.

Hundreds of people paid their respects to Mixner’s life and legacy throughout a service that lasted nearly two hours. Mixner was “a man who devoted his life to cultivating a great bountiful garden of freedom,” New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy said in his 20-minute eulogy.

“A garden big enough for everyone filled with warm resolute Mixner trees with roots reaching deep to bind us together as one community and provide us the nourishment we need to grow into the fullest happiest, confident version of ourselves,” Murphy said, referring to a tree that once stood 3,000 miles away in the People’s Park in Berkeley, California that was a meeting place for anti-Vietnam War demonstrators. The tree also witnessed brutal police beatings of the protestors. Last year, the tree and others in the park were uprooted by the University of California, Berkeley for student housing on the People’s Park.

President Joe Biden was unable to attend Mixner’s funeral. He sent two top gay aides, Gautam Raghavan, assistant to the president and director of presidential personnel, and Jamie Citron, deputy assistant to the president and principal deputy director of the White House office of public engagement.

“For those of us who came out and came of age in the world of politics and public service, the name, David Mixner, meant pride and power,” Raghavan told mourners. “Perhaps one of his greatest legacies is that there are now more of us to do this work in advocacy on campaigns and in the halls of power, not in spite of who we are but because of who we are.”

Citron followed Raghavan, reading a letter from Biden expressing his condolences and paying tribute to Mixner’s life and legacy.

“Through his decades of relentless advocacy, David pushed our country to understand a fundamental truth that nobody should have to be courageous just to be themselves,” Biden wrote. “He helped inspire a vibrant movement for justice that continues to beat in the hearts of countless LGBTQ people across the country.”

Tributes

Tributes poured in on social media and in the media as news spread of Mixner’s death March 11.

LGBTQ+ Victory Fund President and CEO Annise Parker called Mixner “a founding father” of the LGBTQ+ Victory Fund and “our movement for equality” in a March 11 news release.

“David was a courageous, resilient, and unyielding force for social change at a time when our community faced widespread discrimination and an HIV/AIDS crisis ignored by the political class in Washington, DC,” Parker said. Due to the United States government ignoring the needs of the LGBTQ community and the HIV/AIDS crisis, Mixner and a group of activists “determined it was because LGBTQ+ people were not represented among those elected leaders — and that we needed to be in the halls of power to make true change.”

“From that moment, he made transforming our government his life’s work,” she continued, noting the 1991 founding of what was then known as the Gay and Lesbian Victory Fund to exclusively support LGBTQ+ candidates.

Former President Bill Clinton also responded to his friend and trusted advisor’s death, writing on X March 13, “In the more than 50 years since I met David Mixner, I’ve known few people more committed to social justice and so true to their principles. America is a better, fairer, more inclusive place because of his long fight for LGBTQ+ rights and so much more. His legacy endures in the change he made and the generations of leaders he mentored and inspired. I will miss him.”

On March 12, White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre expressed the debt LGBTQ leaders like herself owed to Mixner.

“David was a trailblazer in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights,” Jean-Pierre said. “His moral clarity never wavered, which is why he became such an invaluable confidant for so many, including presidential hopefuls, elected leaders, and the voices of the movement for LGBTQ+ equality.”

“Perhaps most importantly,” she continued, “he was deeply dedicated to mentoring the next generation of LGBTQ+ leaders fighting to create a better world. Those of us doing this work today, including myself, owe him a debt of gratitude.”

Newly confirmed US ambassador to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Sean Patrick Maloney, echoed Jean-Pierre’s sentiment.

“People like me would never have been able to enjoy the careers we have without his sacrifice,” he said in an interview. Mixner, he said, had a “moral voice who took real risks to win our equality, and very often at a high personal cost.”

Life and career

The youngest son of Irish-Catholic immigrants, Mixner was born August 16, 1946, in Bridgeton, New Jersey. He and his two older siblings were raised in nearby Elmer. The Times reported his father, Ben Mixner, worked for a commercial farm, while his mother, Mary Mixner, was a bookkeeper for a John Deere tractor dealer.

Politics grabbed Mixner’s heart and soul when he was in high school. As a teenager, he volunteered for John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1960, according to Metro Weekly, a Washington, DC publication. He recalled in the interview with the Metro Weekly that “it was an essential part of the Irish-Catholic experience to work for Kennedy if you were alive back then.”

Mixner went to Arizona State University and transferred to the University of Maryland to be closer to Washington, the hub of the anti-Vietnam War movement where he met Clinton when the two men were both in their 20s. Those moments sharpened his political eye and connections to the White House when his lifelong friend, Clinton, became the first presidential candidate to publicly court the gay vote during his first bid for the White House in 1992.

“I said, ‘Bill, I’ve lost over 180 friends to AIDS,’” Mixner told the New York Times in 1992. “‘Before I can get behind this campaign, I have to know where you stand on this, where you stand on AIDS and our struggle for our freedom.’”

That year, Clinton became the first presidential candidate to openly embrace 500 gay funders at a fundraiser in Los Angeles.

Clinton told the donors, “What I came here today to tell you in simple terms is, I have a vision and you are part of it.”

Mixner was the first openly gay man to hold a public-facing presidential campaign role when he joined the Clinton campaign’s National Executive Committee, according to the LGBTQ+ Victory Fund. Mixner was credited with pushing Clinton to include more LGBTQ people in key campaigns and he raised $3.4 million for the 1992 Clinton campaign, the Washington Post reported.

Clinton followed Mixner’s priority list for the LGBTQ community, from addressing the HIV/AIDS crisis to placing out LGBTQ people into office in the federal government. However, Clinton broke his promise that he would end discrimination in the military based on sexual orientation when he signed the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, which banned queer military members from serving openly.

Clinton’s compromise caused a deep rift between the two friends and political allies. Betrayed, Mixner publicly opposed “don’t ask, don’t tell.” He also led and was arrested at a protest against the policy outside the White House. Mixner’s public opposition to “don’t ask, don’t tell” froze him out of the White House and cost him his career as a political consultant on the east coast.

“They made it impossible for me to work for four years,” Mixner said in an interview in Variety. “I was banned from the White House, but interestingly enough, I didn’t get much support from the [LGBTQ] community. But that is OK, because I had to do what I thought was right.”

In 1996, Mixner spoke out against Clinton’s signing of the Defense of Marriage Act, which banned federal recognition of same-sex marriage, during his reelection campaign.

However, Mixner launched the LGBTQ+ Victory Fund’s Presidential Appointments Program after Clinton took the White House. The program pushed Clinton’s administration and administrations after that to appoint more out LGBTQ people to key political positions, according to the LGBTQ+ Victory Fund’s statement.

Former president Barack Obama repealed “don’t ask, don’t tell” 18 years later in 2011. The US Supreme Court repealed the Defense of Marriage Act in 2015, legalizing same-sex marriage across the country. Mixner and Clinton later reconciled.

Mixner moved to Los Angeles in the 1970s and co-founded the Municipal Elections Committee of Los Angeles, described by the Online Archive of California as the first gay and lesbian political action committee in the country.

Mixner advised many elected officials’ political campaigns across the country, including Harvey Milk, who was the first openly gay man elected in California when he was voted to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1978. Milk was assassinated with Mayor George Moscone by former supervisor Dan White.

Mixner also served as campaign manager for the 1977 re-election bid of Los Angeles’ first Black mayor, Tom Bradley, and worked for the late antiwar activist Tom Hayden, and many others, reported the Washington Post.

Very persuasive, Mixner also convinced then-Republican California Governor Ronald Reagan to oppose Prop 6, also known as the Briggs Initiative, in 1978. The initiative would have barred LGBTQ teachers from teaching in California public schools. Voters rejected the initiative at the ballot box.

In 2009, Mixner organized the National Equality March in Washington, DC. The march drew tens of thousands of LGBTQ activists and supporters onto the Mall in Washington DC, reported the New York Times.

Mixner recounted his childhood and experience as an openly gay political insider and activist in his memoir, “Stranger Among Friends” (1996), and three plays “Oh Hell No!,” (2014), “1969” (2017), and his one-man play, “Who Fell Into the Outhouse?” (2018). “Oh Hell No!” was performed in New York, Los Angeles, and other cities in 2014, 2015, and 2016, those and stagings of his other plays benefited major LGBTQ organizations, Deadline reported.

Mixner is survived by his brother, Melvin Mixner, according to the New York Times.

Mixner left his last words of wisdom and reflection on his life in an interview for New York City’s Ali Forney Center a week before his death.

Donations in memory of Mixner can be made to the David Mixner Memorial Fund at the Ali Forney Center.