Einsteins “Circus” window display by Greer Lankton and Paul Monroe, with dolls and photo by Lankton. | COURTESY: PAUL MONROE FOR GREER LANKTON ARCHIVES MUSEUM

“Gay Gotham: Art and Underground Culture in New York,” a new exhibit at the Museum for the City of New York, is a terrific survey of a variety of queer subcultures and personalities that once made our now malled-over city so vibrantly the center of the gay universe, and not just because of Stonewall.

A mammoth and wondrously varied effort, it takes up two floors of the museum and is an exhilarating barrage of influences, both high and low, which have in all kinds of ways, affected us all. And, if, like me, you are of a certain age, it really brings home the history we all actually lived, both familiar, and, at times, reminding one of something wonderful and quite forgotten, which suddenly springs to radiant life in your mind’s eye.

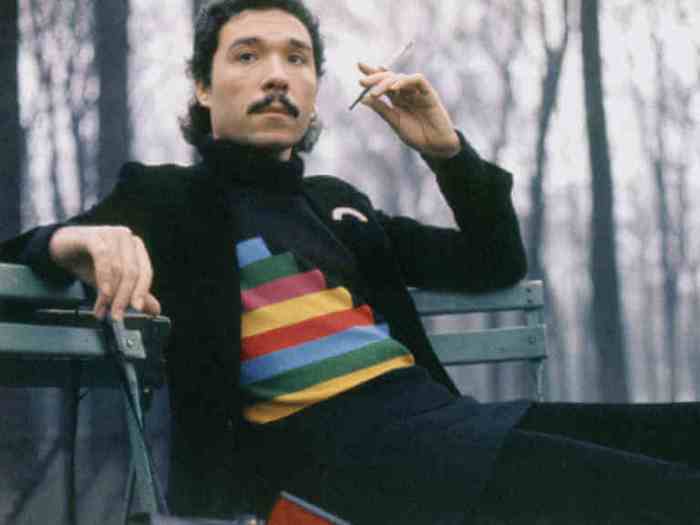

That latter category include to the show’s tribute to the marvelous East Village boutique Einsteins, where I used to pick up pieces of the wildly creative clothing being made by gifted artisans in the New Wave/ Punk, graffiti and disco-driven 1980s. Its resident artist was the brilliant transgender artist Greer Lankton, whose specialty were amazing dolls that were deliriously campy and bizarrely lifelike at the same time. Her huge Diana Vreeland, commissioned for a Barney’s window, is here, and will undoubtedly bring a smile to your face.

“Gay Gotham” memorializes the greatest dyke Casanova of her day

It’s a real feast, from Andy Warhol’s scene to an informal history of gay bars to the inclusion of Christopher Street pier, which once housed a dilapidated building that offered pre- AIDS horny gays a free locale in which to suck, fuck, and boogie 24 hours a day. And, in that pre-Giuliani once upon a time, did they ever! To think that one could shed one’s clothes and then do whatever it is you do when you’re naked in an open public New York space now boggles the mind, making you think, “Did I just imagine that happened?” (Oh, but it did: on my one exploratory excursion there, the overpowering formaldehyde scent of decades of dried up bodily fluids made me do an immediate U-turn.)

Peter Hujuar’s 1976 “Christopher Street Pier #2 (Crossed Legs). | THE PETER HUJAR ARCHIVE LLC; COURTESY: PACE/ MACGILL GALLERY, NEW YORK, AND FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCO

Speaking of naked, Larry Rivers’ monumental full frontal portrait of the brilliant poet Frank O’Hara is on display and, while I applaud the inclusion of that, as well as tributes to Harlem Renaissance pioneering artist Richard Bruce Nugent, photographer George Platt Lynes, and Carl Van Vechten, walls devoted to Warhol, Mapplethorpe, Leonard Bernstein, and Lincoln Kirstein seem a little been there-done that. Although there’s some great, rare stuff here – like a 1950s snapshot of Warhol, looking the ultimate young dweeb, on a tour of Japan, early invitations to shows that illustrate his struggle to make original, non-Abstract Expressionist art, and some gorgeous Irene Sharaff costume sketches for “West Side Story” – one wishes more emphasis had been given to less predictably prominent artists, like innovative deejay Larry Levan, of the legendary Paradise Garage (which doesn’t even get a mention anywhere), or Charles Ludlam and other representatives of maverick downtown theater like John Vaccaro and Tom Eyen. Manhattan’s once-burgeoning 1970s cabaret scene – with clubs galore like Reno Sweeney, Upstairs at the Downstairs, Brothers and Sisters, the Ballroom, the still-going strong Marie’s Crisis right down to funky Club 57 (which is having its own exhibit at MoMA next year) – is also MIA here.

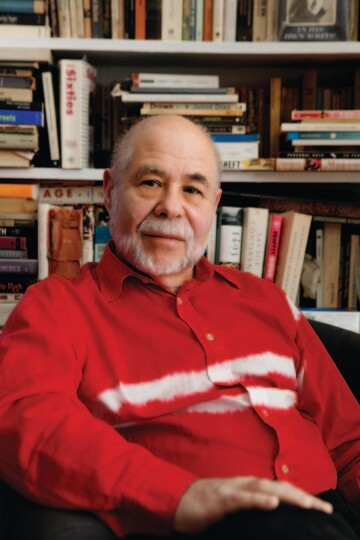

What this show does include is a happily sizable homage to one of the most fascinating, least-known women who ever walked down Fifth Avenue. She wore strictly black and white, which matched her dramatic coloring, favoring short, slicked-back hair, trousers, exotic highwayman coats and capes, tricorn hats, pointy-toed buckled shoes, at one point even an eye patch, prompting Tallulah Bankhead to call her “Countess Dracula,” and another acquaintance to dub her “The Black and White.” That friend was Greta Garbo, and the woman in question here, Mercedes de Acosta (1893-1968), was her lover for a time, something she – de Acosta, that is – never got over.

If ever a person made art of her life, it was truly she, for, as Alice B. Toklas once said of her, “Say what you will about Mercedes, she’s had the most important women of the 20th century.” Garbo must surely count as one of these, followed by Marlene Dietrich (whom de Acosta dated simultaneously), as well as Isadora Duncan, Eva Le Gallienne, Alla Nazimova, actress Ona Munson, and ballerina Tamara Karsavina. There were also rumors her being with Toklas, Eleanora Duse, Katharine Cornell, and Pola Negri. “I can get any woman away from any man,” she once reportedly boasted. Truman Capote was so fascinated by her that he devised a game called International Daisy Chain, a sexual linking version of today’s Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, claiming that de Acosta was the essential pivot, “because, from her, you could get anyone from Cardinal Spellman to the Duchess of Windsor.”

She certainly cast a spell, as evinced by certain tributes from her famous lovers. Isadora Duncan penned a poem about her: “Two sprouting breasts/ Grand and sweet/ Invite my hungry mouth to eat/ From whence two nipples firm and pink/ invite my thirsty soul to drink/ And lower still a secret place/ Where I’d fain hide my loving face.”

Abram Poole’s portrait of his wife of 15 years, Mercedes de Acosta. | COURTESY: SANTA BARBARA MUSEUM OF ART/ GIFT OF MERCEDES DE ACOSTA IN HONOR OF ALA STORY

De Acosta was born in New York City to wealthy, socially prominent Spanish parents. Her father and brother would both later commit suicide, and her sister, Rita, was herself a celebrity, noted for her beauty and chic, who was featured in one of the first Metropolitan Museum Costume Institute exhibits as one of the great “American Women of Style.” When Mercedes was 20, she fell under the wing of theater/ literary agent and producer Bessie Marbury, the lover of society decorator Elsie de Wolfe and lesbian doyenne of Manhattan, who introduced her to notable people. De Acosta was immediately drawn to the world of art and theater, forever dabbling in it, without ever attaining any huge success, although her lover of five years, Le Gallienne, appeared in two failed plays written by her, about Joan of Arc and Botticelli. When de Acosta went to Hollywood, she quickly met and became instantly besotted by Garbo for the rest of her life. I remember borrowing a copy of her memoir, “Here Lies the Heart,” from the library as a kid, and my nascent gaydar going off when I saw the topless candids of the elusively private star while on vacation in the Sierras with de Acosta.

On April 15, 2000, 10 years after Garbo’s death, the seal was lifted on de Acosta’s papers pertaining to her, as per the stipulation in her will. The papers, housed at the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia, included 55 letters from the star, which ironically had long shared the same box as de Acosta’s letters from Dietrich, which had had their own seal until that star’s death in 1992. Garbo’s surviving family seems bent on maintaining a heterosexual status for her, denying any lesbianism on her part and forbidding any of her letters to be directly quoted for publication. Evidently, two humorous, foot-related pieces of memorabilia were included among the papers, which neatly symbolize de Acosta’s contrasting relationships with the two stars. There’s the flirtatious and sexy inclusion of a single silk stocking from Dietrich (who unguardedly poured out her love, addressing her missives “mon grand amour” and in phrases like “[those] exquisite moments when I was in your arms that afternoon”), while Garbo sent her the drawn outline of her foot, all the better to have the ever servile de Acosta have shoes made for her.

The fanaticism with which de Acosta worshipped Garbo is easily evinced in her personal Bible, on display in this new exhibit, in which she has pasted photos of her screen queen beloved in the pages. While the Dietrich affair was brief and passionate – before that restlessly romantic diva moved on to other loves, like writer Erich Maria Remarque, Jean Gabin and tattooed butch dyke millionaires Joe Carstairs – her friendship with Garbo – with De Acosta’s virtual stalking and the star’s skittishness and selfishness making their road an always rocky one – managed to last until 1958, a few years before her memoir was published.

Although not salacious in any way, just the hints of intimacy between her and Garbo prompted the latter to completely ice her out for the rest of her life, with de Acosta’s own lifelong rival for her affections, the equally Garbo-crazy Cecil Beaton, expressing shock at how coldly and callously she slammed the iron door on a decades-old relationship he always thought would continue with just the two of them together in advanced old age. The redoubtable Le Gallienne also took great umbrage at the book and would storm out of the room if de Acosta’s name was so much as mentioned. A decade after de Acosta’s death, a friend of Le Gallienne’s found a gold wedding band in her attic and asked what it was. “It was from Mercedes,” came the actress’ snarled reply, before she threw it into a well. She opined that her erstwhile lover’s book should have been titled “Here Lies the Heart, and lies, and lies, and lies.”

De Acosta’s later years were challenging, to say the least. She stopped writing, suffered severe health problems and mishaps, and was financially straitened, living in a tiny apartment on East 68th Street. Although ex-lovers like Dietrich helped her out, she was forced to sell her jewels and correspondence. She admitted to being known as “the dyke at the top of the stairs”, deserted by famous friends because of her poverty, with her only visitors being rapacious young women hoping to meet Garbo.

At her death, Beaton wrote, “I cannot be sorry at her death. I am only sorry that that she should have been so unfulfilled as a character. In her youth she showed zest and originality. She was one of the most rebellious & brazen of lesbians… I am relieved that her long drawn out unhappiness has at last come to an end.” She is buried at Trinity Cemetery in Washington Heights.

Although she was more famous for who she did than what she did, de Acosta’s importance is assured, if only as an early example of a woman who, come good fortune or bad, and in the face of the strict homophobia of her time, resolutely lived her life with total independence. And it was a life ahead of its time, which included a 15-year marriage to a man, Abram Poole, whose magnificent life-sized painting of her dominates the gallery. She was a suffragette and tireless warrior for women’s rights, a vegetarian and fur-shunning animal lover. Although raised Catholic, she embraced Buddhism and immersed herself in Hindu philosophy, yoga, and meditation.

In 1928 de Acosta wrote a novel, “Until the Day Break,” about a woman who is confused by her sexual longings: “I have had more emotion through women; they give me a sense of beauty… As for worrying about the sex end of it, that seems to be unimportant. In America, I suffered much. They are not old enough to comprehend these things. It is perhaps their youth, which does not recognize that real love is real love, no matter whom it is for… It is curious. The world does not blame people for having black or blonde hair They are just born that way and it is accepted. But for something deeper, for something more ‘you’ than the color of hair or eyes, one is condemned. They do not realize that God made each one for some ultimate reason; with his own salvation to work out, a pattern to follow and unfold, as his own spirit sees it.”

GAY GOTHAM: ART AND UNDERGROUND CULTURE IN NEW YORK

Museum of the City of New York

1220 Fifth Ave. at 103rd St.

Through Feb. 26, 2017

Daily, 10 a.m.-6 p.m.

mcny.org/exhibition/gay-gotham

Cecil Beacon’s 1969 photo of Andy Warhol and Candy Darling. | THE CECIL BEATON STUDIO ARCHIVE AT SOTHEBY’S