Léa Seydoux plays the title character Célestine in Benoît Jacquot’s “Diary of a Chambermaid,” based on Octave Mirbeau’s 1900 novel. | COHEN MEDIA GROUP

Octave Mirbeau’s 1900 novel “Diary of a Chambermaid” has been adapted to film three times. Jean Renoir, Luis Buñuel, and French director Benoît Jacquot have all taken a crack at it. Each version differs from Mirbeau’s original in significant ways.

Jacquot’s take suggests that some things remain eternal. Most are negative: classism, anti-Semitism, sexual harassment. There’s also the enduring appeal of the “bad boy,” if that term applies to a man in his 50s. The character with whom Jacquot’s chambermaid falls in love may be guilty of all sorts of crimes, but he’s representative of a world where a man breaks the neck of his “beloved” pet ferret and orders it made into a stew just to prove a point.

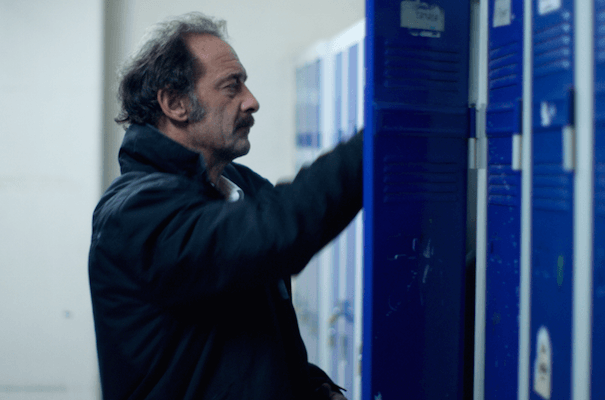

Léa Seydoux plays the title character Célestine, following Paulette Goddard (in Renoir’s version) and Jeanne Moreau (in Buñuel’s). She wants to stay in Paris but can’t find a job there. She does get a job in provincial France, but treats the experience as an exile from the capital. Her mistress (Clotilde Mollet) gets mad if she eats a prune or two from the household inventory and spends her day ringing the bell that calls for Célestine’s service. Her master (Hervé Pierre) keeps groping her. She finds the gardener Joseph (Vincent Lindon) fascinating.

Third adaptation of “Diary of a Chambermaid” plumbs dark corners in a young woman’s libido

According to the news, anti-Semitism has been on the rise in France lately. The country doesn’t seem to have learned much from World War II, now more than 70 years in the past. French Jews are emigrating to the UK, North America, and Israel. This climate inspired Jacquot to explore the roots of French anti-Semitism through the character of Joseph, the filmmaker suggesting that 20th-century anti-Semitism got its start in France, not Germany. Joseph says horrible things like “The Jews should all be disemboweled” and contributes to a newspaper called Le Petit Parisien, which offers up anti-Semitic headlines and caricatures.

Célestine argues with him about the Jews, saying that they behave no worse than any other religious group, yet in the end she tolerates his anti-Semitism as the price of his company. It may even add a frisson to Joseph’s sex appeal.

In an interview, Jacquot explains Joseph’s seductiveness this way: “Despair and poverty can easily lead to finding the most apocalyptic of discourses appealing. Célestine is attracted by the radical energy that Joseph exudes and which fits in with the radicalism of the times, a populism marked by anti-Semitism.”

Jacquot’s “Diary of a Chambermaid” isn’t far off from Susan Sontag’s essay about the dark but lingering appeal of fascist director Leni Riefenstahl’s films and photos.

Jacquot is working in a more permissive environment than Renoir or even the famously kinky Buñuel were. (A scene of Joseph scrubbing his feet seems a nod to Buñuel’s foot fetish.) As a result, his “Diary of a Chambermaid” is the most sexually explicit film version yet. That doesn’t mean it’s particularly erotic, however. Jacquot associates sex with humiliation, even death, and constantly reminds the modern-day spectator of the risks of sex — often forced by men upon women — before reliable contraception. At a border crossing, a proper lady is embarrassed when she’s forced to open a locked contraption; while she insists that it contains jewelry, it proves to hold a dildo. Célestine’s embrace kills a tubercular man during coitus, with both their faces smeared with blood.

It would be easy to turn Célestine into a heroine whom everyone could admire and easily identify with. Jacquot is after something more complicated. To a large extent, she’s defeated by her libido. She has few options, and her situation is mocked by the pastel world in which she moves. Her costumes are studiously pretty, as is the décor of the manor where she toils. Jacquot tracks this world with zooms.

“A Single Girl,” which followed a young hotel maid for 90 minutes in real time, is the Jacquot film that “Diary of a Chambermaid” most resembles. If “Diary of a Chambermaid” is a disguised portrait of the present, things have gotten much worse in the 20 years between 1995, when “A Single Girl” was made, and now.

DIARY OF A CHAMBERMAID | Directed by Benoit Jacquot | Cohen Media Group | In French with English subtitles | Opens Jun. 10 | Lincoln Plaza Cinema, 1886 Broadway at W. 62nd St. | lincolnplazacinema.com