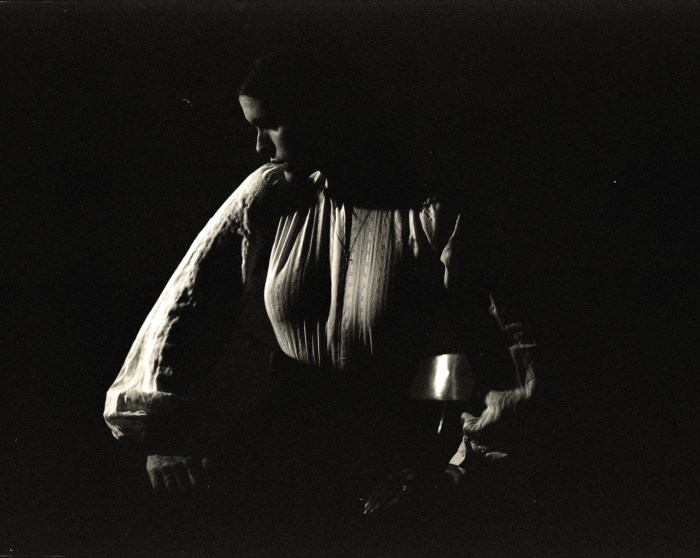

The Metropolitan Opera is at the midpoint of Wagner’s mythical tetralogy “Der Ring des Nibelungen,” an epic driven by a ring made of cursed gold that destroys those who try to control it. In Giacomo Meyerbeer’s pastoral opéra-comique “Dinorah, où Le Pardon de Ploërmel” (1859), the Breton goatherd Hoël abandons his fiancée Dinorah at the altar to chase after a trove of ancient gold which is protected by a fatal curse. The first man to touch the gold will die. The jilted Dinorah proceeds to go melodiously mad singing roulades up and down the wild forest mountains of Brittany while chasing her goat Bellah.

Wagner’s “Ring Cycle,” though hugely expensive and difficult to perform, has regularly returned to the repertory of the Metropolitan Opera since 1892. Meyerbeer’s “Dinorah,” a pastoral romance with supernatural elements, racked up only five performances at the Met (two were on tour), with the last occurring in 1925 as a vehicle for Amelita Galli-Curci. Meyerbeer’s opéra-comique is mainly known today through one aria — the coloratura showpiece “Ombre légère” or “The Shadow Song” (famously recorded by Galli-Curci, Lily Pons, and Joan Sutherland, among others). Ironically, it was Wagner’s cruelly anti-Semitic attacks on Meyerbeer and French Grand Opera in his pamphlet “Jewry in Music” (along with changes in public taste and style) that caused Meyerbeer’s operas to be consigned to the attic trunk along with all the other mid-19th century white elephants.

The intrepid Amore Opera Company, in March, provided the first chance in nearly a century to see this once-famous and beloved opera staged and performed live. It was also the local premiere of the original French-language opéra-comique version (Galli-Curci and Luisa Tetrazzini performed the opera in Italian with recitatives). Amore Opera is the successor to the scrappy but endearing Amato Opera. The singers are local, the orchestra (Amato used two pianos) is a bunch of volunteer amateurs, the costumes are recycled, and the sets are modest painted flats. Everything, including the intermission treats, is homemade and prepared with love. According to Nathan Hull, the company director, this is the opening salvo in a Meyerbeer cycle performed on the tiny stage of the Riverside Theatre near Columbia University uptown. “L’Étoile du Nord” is on the docket for next season. Whatever the limitations of Amore Opera’s resources, the small company made a strong case that “Dinorah, où Le Pardon de Ploërmel” as a viable, imaginatively orchestrated, and melodically rich work burdened by an implausible libretto in the hopelessly outmoded pastoral sentimental drama genre.

The colorful painted sets by scenic designer Richard Cerullo had a naïve quality suggestive of children’s theater, bolstered by the use of small children playing various livestock — including two adorable tykes alternating as Dinorah’s pet goat Bellah (who plays an equivocal but crucial role in the plot). The deliberate naïveté was appropriate for such a far-fetched and simple minded story. Conversely, Claire Townsend’s rather sophisticated upper-class Parisian frock coats and gowns for the leads hardly suggested the folk costumes of Breton peasantry.

Director Nathan Hull strove to tell the story simply, faithfully, and directly, and he translated the French dialogue into colloquial English while the sung material was performed in passable French. The volunteer orchestra (either very young or very senior) was a fly in the ointment — ensemble and tuning were haphazard, though the violins and horns settled in somewhat by the end of the evening. Other small companies like Dell’Arte use a smaller group of more professional, paid players in chamber orchestra reductions — this seems like a more practical and artistically pleasing solution.

There were two alternating casts. On opening night, Holly Flack’s Dinorah unleashed a classic high-placed French light coloratura soprano with neat trills and accurate cadenzas in “Ombre légère,” capping the famous aria with a high A-flat above high C — shades of Mado Robin! Flack enacted the fey character with girlish charm. Her alternate, Jennifer Moore, has a larger, more substantial coloratura voice that could handle “La Traviata,” and her more mature, serious presence hinted at real madness and potential tragedy. Moore’s “Shadow Song” was also nimble and fleet, capped by a secure high D.

In the first cast, Suchan Kim’s energetic stage presence and virile baritone as the antihero Hoël made an overwhelmingly positive impression. Only his high notes sounded a bit strained and disconnected from the core of a fine, substantial voice. His alternate, Nobuki Momma, possessed a more modest baritone but had greater suavity in his acting and phrasing. As the doltish, cowardly bagpiper Corentin (Hoël’s intended stooge and cursed gold victim), Juan Hernández was endearingly goofy and sang with a sweet tenor tone. Michael Celentano’s tenor was grainier and rougher, and his acting evoked Sean Penn’s Jeff Spicoli in “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” (that is probably a good thing in the wrong place).

Conductor Richard Cordova was a true hero of the evening leading his uneven ensemble in a rhythmically buoyant reading of the score. His baton is elegant and precise though his players were not. At the final curtain, Dinorah, after abandonment and long travails, is restored to sanity and happily goes to the altar. It seemed a deserved happy ending and a resurrection for both the title character and Meyerbeer’s charming pastoral opera.