Marco Scozzaro’s 2011 photograph of Editta Sherman at age 99. | NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

At the New-York Historical Society right now, you can meet the best unknown portrait photographer of the last century, Editta Sherman. Although she died four years ago, her presence is very much alive here in the huge, vintage 8×10 camera with which she plied her trade (the same one the great George Hurrell used to glorify Golden Age Hollywood stars), the flamboyant hats and garments which made her such a vivid presence around town (captured on film by her great champion and neighbor, Bill Cunningham), and, especially, the glowing, ravishing records of the famous faces who traipsed through her Carnegie Hall studio to pose for her.

Editta Sherman’s undated photograph of Lillian Gish. | NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

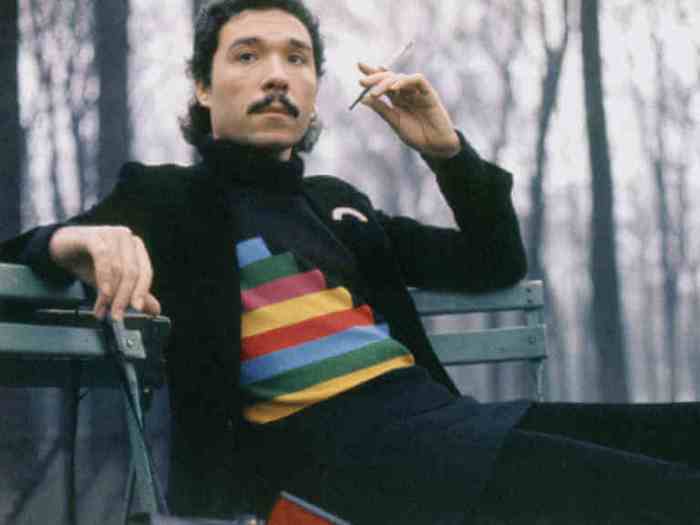

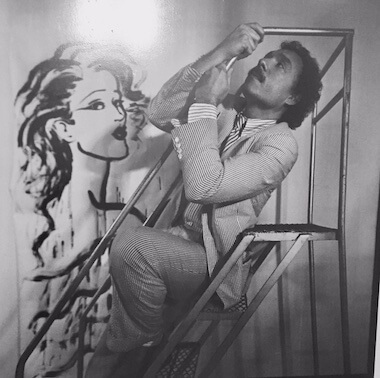

There they are, the truly greats, the likes of which shall never be seen again, surely not in this paltry age of Kardashians and Kevin Harts: Lillian Gish, looking beyond lustrous, the Queen of the World; my favorite actor, Charles Boyer, suavely omniscient; the great, forgotten black actor, Canada Lee; Gladys Cooper, doyenne to die for; Gertrude Lawrence, proving that conventional beauty has really little to do with absolute, innate glamour; the monumental profile of Basil Rathbone; Bela Lugosi, unashamedly striking a threatening Dracula pose; Tyrone Power, a Sherman favorite, the handsomest of matinee idols; Angela Lansbury at the pinnacle of her “Mame” fame; fellow shutterbug Andy Warhol; Carl Sandburg; Leopold Stokowski; what looks to be one of Sherman’s last works, Tilda Swinton, looking an androgynous double for David Bowie in platinum pompadour and bespoke suit; and the best portrait ever, in color, of Antonio Lopez, greatest of all fashion illustrators, who elevated his métier to art.

Dubbed by Cunningham the “Duchess of Carnegie Hall,” Sherman was born Edith Rinaolo in 1912, in Philadelphia, and grew up assisting her Italian immigrant father, himself a wedding and portrait photographer. In 1935, she married Harold Sherman, a sound engineer, with whom she had five children. Her husband’s ill health from diabetes necessitated her making a living with her camera, and she began taking pictures of celebrities on Martha’s Vineyard in the 1940s, using her formidable charm to coax them in front of her lens. The family moved to New York in 1948 and lived in Studio 1208, atop Carnegie Hall, which was only 900 square feet with a bathroom down the hall.

A farewell and salute to two great artists

Editta Sherman’s undated photograph of Canada Lee. | NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

When it was discovered that the studio was not zoned to accommodate families, the children were shipped off to a Staten Island group home. Harold died in 1954, and Editta hustled even harder to make her own way as a rare woman commercial photographer. Her friendship with Cunningham resulted in his book “Facades,” which was a series of portraits by him of her dressed in their shared collection of antique clothing against the backdrop of various New York historical landmarks (reprinted and on sale at the museum).

In 2007, all studio tenants were informed by the City of New York, Carnegie Hall’s owner, that they had to move. Editta was one of the few tenants who resisted eviction and continued to live there, under siege, until 2011, when she moved to a Central Park West apartment. It was there that she died in 2013, age 101.

During the eviction proceedings, the wonderful filmmaker Josef Astor made a film about her and other Carnegie Hall holdouts, “Lost Bohemia” in 2011. For this exhibit, he culled various outtakes from that film and made a short movie, starring Editta. which delightfully records her flamboyant personality, entertaining friends with chatter and pasta and reminiscing about her colorful past.

The death of Jeanne Moreau last month at 89 touched the heart of any true lover of cinema, and I was no exception. Her distinctively morose beauty, cigarette smoke forever wafting from her bewitchingly sullen mouth, was often redolent of Bette Davis, but she surpassed even that great actress with a gallery of performances that positively defined the modern woman while breaking all manner of social and moral barriers imposed on her.

Jeanne Moreau in Jacques Demy’s 1963 “Bay of Angels,” at the Film Forum September 1-7. | FILMFORUM.ORG

From her twin breakout performances in 1958, in Louis Malle’s “Elevator to the Gallows” and “The Lovers,” which made her an international star, through Roger Vadim’s “Les liaisons dangereuses,” Michelangelo Antonioni’s “La Notte,” Joseph Losey’s “Eva,” Luis Buñuel’s “The Diary of a Chambermaid,” Francois Truffaut’s “The Bride Wore Black,” to Bertrand Blier’s “Going Places,” André Téchiné’s “French Provincial,” and so many others, she simply was the face of French cinema, Deneuve be damned.

Her greatest achievement was probably in Truffaut’s “Jules and Jim” (1962), as the irresistibly chameleonic, turbulent Catherine, with her wondrous Georges Delerue/ Serge Rezvani song “Le Tourbillon.” That film, with repeated viewings, basically taught me conversational French in a way three years of high school classes never could.

I was privileged to meet her on the occasion of “Cet amour-la,” Josée Dayan’s 2003 film in which she played cultural icon Marguerite Duras having a famous love affair with a younger man, the writer Yann Andréa. She was doing an interview with me and about five other journalists, one of those dreaded round table affairs. They always make me loathsomely feel like I’m a student back in school vying for the teacher’s attention, made worse by the other writers often knowing little or nothing really about the interviewee and posing inane questions.

Moreau, who spoke perfect English (from childhood), took a shine to me and, after everyone had disbanded, we had a special moment in which she expressed gratitude for my knowledge about her film and Duras. And it was then that I experienced what an incredible seductress she was, for she expressed admiration of a fake fur Lindeberg coat I was wearing, caressing it and saying how she wanted one just like it. And then, she caressed my cheek, saying to the publicist, “Doesn’t he remind you of Aymeric [Demarigny, her co-star]?” As he was not only French but considerably younger than me, this took me aback a little, but I recovered soon enough when, walking me to the elevator, the publicist said, “Boy, she really liked you. I mean she really liked you!”

This emboldened me to leave a photograph of her at the Mayflower Hotel where she was staying, with a thank you note. A day later, the photo was returned to me by mail, autographed by her in gold ink, with an inscription that gave me chills. I will treasure it all my life.

The photo was of Moreau, platinum blonde, in one of her greatest roles, as a compulsive lady gambler in Jacques Demy’s enchanting “Bay of Angels.” Film Forum is reviving this September 1 – 7, and I urge anyone who loves her, or needs to be introduced to her, to revel in and be utterly enslaved by her magical charisma.

THE DUCHESS OF CARNEGIE HALL: PHOTOGRAPHS BY EDITTA SHERMAN | New-York Historical Society | 170 Central Park W. at W. 77th St. | Through Oct. 15: Tue.-Thu., Sat., 10 a.m.-6 p.m., Fri., 10 a.m.-8 p.m.; Sun. 11 a.m.-5 p.m. | $21; $16 for seniors; $13 for students at nyhistory.org

BAY OF ANGELS | Directed by Jacques Demy | Film Forum, 209 W. Houston St. | Sep. 1-7 | filmforum.org