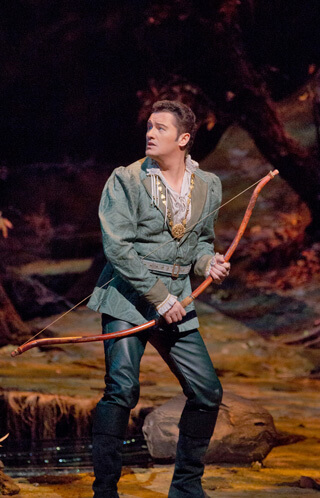

Greer Grimsley (top) and Keith Jameson in “Billy Budd” at the Los Angeles Opera. | ROBERT MILLARD

BY DAVID SHENGOLD | As snow hung tough into March, I visited San Diego and Los Angeles, both cities with notable LGBT scenes as well as first-class theaters. San Diego’s beautiful park-girt Old Globe Theater was playing “Winter’s Tale,” directed with variable success by its new head, Barry Edelstein.

The show often looked ravishing, with superb 1980s glam costumes (Judith Dolan) and wonderfully calibrated lighting (Russell H. Champa). On March 13, the play’s power eventually came through, but was undermined by Edelstein’s scattershot comic lunges (much goo-goo talk at baby Perdita) and hapless direction of rustic scenes; by Michael Torke’s new piano score, often punctuating monologues or played cocktail-style under dialog, wreaking havoc with meter and intelligibility; and by three weak central performances: TV star Billy Campbell, handsome as a Greek statue and about as credible in emotion and speech, flailing as Leontes (granted, a wickedly tough part); Natacha Roi’s singsong, ineloquent Hermione; and a self-enchanted turn by Paul Kandel, doubling Autolycus and Archidamus as a multi-style cabaret act.

Some fine work in support, notably by Angel Desai’s elegant, magisterial Paulina, Cornell Womack’s commanding Camillo, Paul Michael Valley’s well-modulated Polixenes, and A. Z. Kelsey’s vocally compelling, metrically alert Florizel. Perdita was Maya Kazan, sometimes verbally mannered but with definite and pleasing theatrical presence.

Old Globe produces much fine work, but this mixed offering made verbal clarity a disturbingly low priority from Shakespearean veteran Edelstein.

Opera in San Diego and Los Angeles

Shakespeare’s themes of jealousy’s perils and a monarch’s whims comingled well with San Diego Opera’s “Un ballo in maschera” March 14, a traditional staging by Leslie Koenig most distinguished by John Conklin’s resplendent period costumes and by apt star casting in four roles. Debuting conductor Massimo Zanetti dawdled, but gauged his principal duo’s vocal abilities sensitively and left them room to phrase.

Piotr Beczala’s Gustavo took Nicolai Gedda as model. Slightly brassy and effortful in Act One, he discovered more charm, tonal warmth, and dynamic variety thereafter. Krassimira Stoyanova gave a master class in how a lirico-spinto can successfully present a dramatic soprano role; both arias, especially “Morrò,” had beauty and meaning.

Stephanie Blythe (Ulrica) and Kathleen Kim (Oscar) improved on their already fine Met showings, the mezzo more nuanced and the coloratura less chirpy and pert. Aris Argiris (Anckarström), often flat and unsteady, proved disappointing –– another Figaro evidently courting vocal deterioration in grasping at the Verdi baritone mantle.

Los Angeles Opera boasts a fine music director in James Conlon, who helmed both “Lucia di Lammermoor” (March 15) and “Billy Budd” the next afternoon. “Lucia” suffered from some opening night jitters in pit and onstage, causing some evident wrong notes, but Conlon and director Elkhanah Pulitzer gave us the complete score, even the post-Mad Scene recit. Hearing a glass harmonica was also a rare treat.

Pulitzer, presenting “Lucia” in patriarchal Victorian Industrial society, stylized the chorus but relied too heavily on sometimes striking, sometimes painfully over-literal video effects (mention blood and the scrim or stage would redden). When left abstract, Carolina Angulo’s designs (principally geometric forms lit by genius Duane Schuler) were quite beautiful. The major music-dramatic lapse: the chorus met the news of Lucia’s murdering her bridegroom with absolute indifference –– no horror registered in their even vocalizing.

To my tastes the other music-dramatic lapse was the lack of a convincing Lucia. Albina Shagimuratova, an excellent Queen of the Night, started rather cold-voiced but soon showed her remarkable clear, limpid upper register. She made some gorgeous individual sounds, yet sang with little intensity and no sense of internalized textual connection. Her sole expressive device was skillful diminuendi. Hers is no mere tweety–bird voice — it’s rounder and fuller, rather like Luba Organosova’s, and pleasant to hear, but in verbal and dramatic terms (three completely unconvincing faints in one scene), it was as if Callas, Scotto, Sills, and Dessay never brought their insights to this part. The audience loved her.

I find this was my 26th “Lucia”; every Mad Scene has reaped wild ovations, fully deserved or not — it’s a feat to get through it, and high E flats (which Shagimuratova dispenses well) are Pavlovian triggers.

Saimir Pirgu’s Edgardo started rather pushed, and he tended to a hard-shelled holler under pressure. But the voice softened as he went along. It’s clear that the ardent young Albanian has a fine instrument, and he achieved some nuance and distinction in the love duet and in Donizetti’s wonderful final scene.

Remember City Opera’s 2003 “pregnant Lucia” staging, in which only Stephen Powell’s Enrico did the music full justice? Happened again here, due to his combination of oakish resonance, flexibility, and fine diction.

James Creswell voiced Raimondo with clarity and point. Despite one overdriven note, Vladimir Dmitruk’s Arturo served notice of leading tenor quality.

Francesca Zambello’s “Billy Budd” production, directed here by Julia Pevsner, has a typically ambitious scale and –– in Act Two’s opening out of the ship into two decks — some visual coups de théâtre. Pevsner’s leads — save for Richard Croft’s beautifully sung and uttered Vere, a terrific performance New York should hear –– didn’t always fully react to the libretto’s many subtleties. Croft, rather than Liam Bonner’s pedestrian Billy, anchored the show.

Tall and affably handsome, Bonner lacked both the vocal quality (a tremolo pertains at all but full tilt) and moral stature for this potentially devastating iconic role. Greer Grimsley made a James Morris-like growling Claggart, reasonably effective but not “dark bass” enough in timbre and not yet commanding all the text’s nuances.

Daniel Sumegi (Flint) and Anthony Michaels-Moore (Redburn) sounded rather fatigued, but gained in stature in the trial scene. Best of Vere’s officers vocally was Patrick Blackwell’s resonant Ratcliffe.

Besides Croft — unforgettably expressive and dulcet in this role debut –– three tenors shone: Greg Fedderly (Red Whiskers), Dmitruk, again (Maintop), and especially Keith Jameson (Novice). Creswell did well by Dansker. Here Conlon excelled, and the company’s male chorus really earned their ovations.

One caveat to travelers, for whom both cities offer many enticements –– taxis, more or less indispensable unless friends are driving, proved piratically expensive, making me proud of New York’s public transit, which rich and poor alike take to performances.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.