A federal appeals panel has ruled that a California statute outlawing so-called sexual orientation conversion therapy for patients under 18 is constitutional. The Ninth Circuit ruling, on August 29, came in response to two lawsuits, based primarily on First Amendment free speech grounds, that had delayed implementation of the law, which bans state-licensed mental health providers from conducting “sexual orientation change efforts” (SOCE) on minors.

Most significantly, the court ruled that the practice of SOCE, though it mainly involves talking by the therapist and patient, is not “speech” protected by the First Amendment, but rather a medical practice that incidentally involves speech.

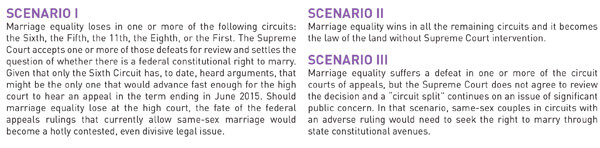

Ninth Circuit draws distinction between limits on speech and restrictions on mental health practices

Writing for the court, Circuit Judge Susan P. Graber first summarized mental health profession thinking about SOCE, which in decades past included aversive methods such as lobotomies, shock treatment, and induced nausea, now disavowed by nearly all practitioners. The plaintiffs’ assertion that their approach now relies almost entirely on talk therapy formed the basis of their First Amendment claims.

Beginning with the American Psychiatric Association in 1973, major professional health organizations have declared that homosexuality is not a mental illness and consequently rejected SOCE as unnecessary and ineffective. The California legislature, in debating its SOCE restrictions, considered anecdotal evidence from professional associations that the practice can, in fact, be harmful.

The law does not impose criminal penalties on therapists for providing SOCE to minors, but makes it a basis for loss of a license for unprofessional conduct. Judge Graber points out licensed therapists remain free to talk about SOCE, to advocate it publicly, to recommend it to their minor clients — who would have to go out of state to receive such “treatment” or rely on non-licensed individuals such as religious-based practitioners. The law, Graber concluded, “regulates the provision of medical treatment, but leaves mental health providers free to discuss or recommend treatment and to express their views on any topic.”

Examining the difficult line between regulation of speech and of conduct in the context of mental health care, Graber “distill[ed] the following relevant principles” from prior cases: “(1) doctor-patient communications about medical treatment receive substantial First Amendment protection, but the government has more leeway to regulate the conduct necessary to administer treatment itself; (2) psychotherapists are not entitled to special First Amendment protection merely because the mechanism used to deliver mental health treatment is the spoken word; and (3) nevertheless, communication that occurs during psychotherapy does receive some constitutional protection, but it is not immune from regulation.”

The California law, she concluded “regulates only treatment,” not speech in and of itself. “We conclude that any effect it may have on free speech interests is merely incidental.” The state, therefore, did not have to meet the substantial judicial burden required when limiting speech. Graber found that “protecting the well-being of minors is a legitimate state interest,” the appropriate test of the law’s constitutionality.

With few exceptions, the court noted, the mainstream of professional organizations in the medical and mental health fields has arrived at “the overwhelming consensus” that “SOCE was harmful and ineffective.” Graber wrote, “On this record, we have no trouble concluding that the legislature acted rationally by relying on that consensus.”

On the question of whether the law interfered with parental rights, the court pointed out that both prohibitions of and requirements for specific medical treatments have been upheld. For example, compulsory vaccination schemes have been upheld over the protest of parents, and the courts have stepped in to mandate medical treatments rejected by parents on religious grounds.

The plaintiffs will undoubtedly seek further review, but the Ninth Circuit is unlikely to allow further delay in implementing the new law.

The State Attorney General’s Office defended the statute, and the National Center for Lesbian Rights was allowed to participate representing intervenors, with its legal director, Shannon Minter, arguing before the Ninth Circuit panel.

The court’s decision may prove influential outside the Ninth Circuit, as a legal challenge gets underway in New Jersey to a similar statute recently signed into law by Governor Chris Christie. In New York, State Senators Brad Hoylman and Michael Gianaris and Assemblywoman Deborah Glick hailed the Ninth Circuit ruling and pressed the legislature in Albany to act on similar legislation.