NEW YORK (AP) — The wave of attempted book banning and restrictions continues to intensify, the American Library Association reported September 16. Numbers for 2022 already approach last year’s totals, which were the highest in decades.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. “It’s both the number of challenges and the kinds of challenges. It used to be a parent had learned about a given book and had an issue with it. Now we see campaigns where organizations are compiling lists of books, without necessarily reading or even looking at them.”

The ALA has documented 681 challenges to books through the first eight months of this year, involving 1,651 different titles. In all of 2021, the ALA listed 729 challenges, directed at 1,579 books. Because the ALA relies on media accounts and reports from libraries, the actual number of challenges is likely far higher, the library association believes.

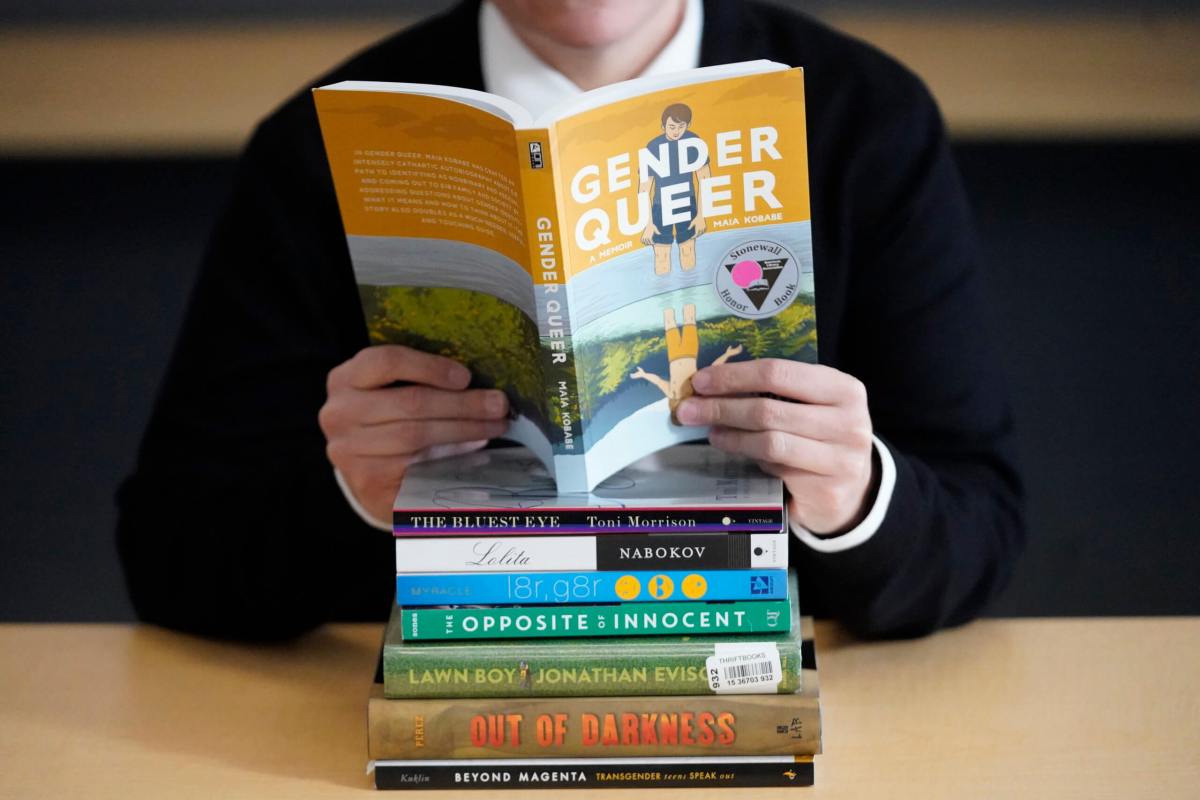

The announcement was timed to coincide with Banned Books Week and it will be promoted around the country through table displays, posters, bookmarks and stickers and through readings, essay contests and other events highlighting contested works. According to a report issued in April, the most targeted books have included Maia Kobabe’s graphic memoir about sexual identity, “Gender Queer,” and Jonathan Evison’s “Lawn Boy,” a coming-of-age novel narrated by a young gay man.

“We’re seeing that trend continue in 2022, the criticism of books with LGBTQ subject matter,” Caldwell-Jones says, adding that books about racism such as Angie Thomas’ novel “The Hate U Give” also are frequently challenged.

Banned Books Weeks is overseen by a coalition of writing and free speech organizations, including the National Coalition Against Censorship, the Authors Guild and PEN America.

Conservative attacks against schools and libraries have proliferated nationwide over the past two years, and librarians themselves have been harassed and even driven out of their jobs. A middle school librarian in Denham Springs, Louisiana, has filed a legal complaint against a Facebook page which labeled her a “criminal and a pedophile.” Voters in a western Michigan community, Jamestown Township, backed drastic cuts in the local library over objections to “Gender Queer” and other LGBTQ books.

Audrey Wilson-Youngblood, who in June quit her job as a library media specialist in the Keller Independent School District in Texas, laments what she calls the “erosion of the credibility and competency” in how her profession is viewed. At the Boundary County Library in Bonners Ferry, Idaho, library director Kimber Glidden resigned recently after months of harassment that included the shouting of Biblical passages referring to divine punishment. The campaign began with a single complaint about “Gender Queer,” which the library didn’t even stock, and escalated to the point where Glidden feared for her safety.

“We were being accused of being pedophiles and grooming children,” she says. “People were showing up armed at library board meetings.”

The executive director of the Virginia Library Association, Lisa R. Varga, noted that librarians in the state have received threatening emails and have been videotaped on the job, tactics she says that “are not like anything that those who went into this career were expecting to see.”

Becky Calzada, who is the library coordinator for the Leander Independent School District in Texas, says she has friends who have left the profession and colleagues who are afraid and “feel threatened.”

“I know some worry about promoting Banned Books Week because they might be accused of trying to advance an agenda,” she says. “There’s a lot of trepidation.”