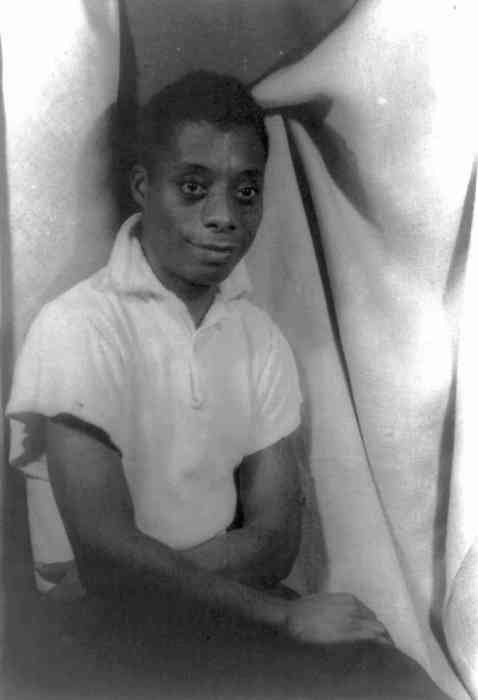

The prolific James Baldwin, one of the most influential American writers of the 20th century, employed a variety of genres in his literary mission to lay bare the structures of racism. He authored novels, plays, memoir, poetry, screenplays, political commentary. But, movie reviews? One of Baldwin’s lesser discussed outputs is a short but multi-layered book about movies titled “The Devil Finds Work.” Published in 1976, it revisits a diverse selection of Hollywood box office successes, with and without Black cast members, analyzing entire plotlines, as with “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” (1967), or plucking out isolated performances or the screen presence of particular icons for scrutiny.

Characteristically Baldwin, the criticism is interwoven with the author’s personal recollections of responding to movie images. He describes the icons and images that informed his sense of self. Baldwin’s aim is to instruct readers in the myriad ways that Hollywood movies, and the industry in general, are instrumental in normalizing, promoting even, a racial hierarchy in society.

The Devil in the essay’s title is therefore Malcolm X’s blue-eyed Devil, the term the civil rights leader used in his early years of activity in the Nation of Islam to name the racial oppressor, but it could also be thought of as Baldwin himself, devilishly carrying out his intellectual work of desacralizing Hollywood’s screen images.

I was introduced to “The Devil Finds Work” in a college film studies class. Now that I am myself a professor of Media Industry Studies, I occasionally assign it to be read in one of my classes. And now, it is compelling for me to consider what Baldwin might have to say about the month-long film festival opening January 17 at the Film Forum, “Black Women: Trailblazing African American Performers & Images, 1920–2001.” The festival includes a number of the films to which Baldwin gives his attention in “The Devil Finds Work.” The series is programmed by the film historian Donald Bogle, who has authored, most recently, “Hollywood Black: The Stars, the Films, the Filmmakers,” and Ina Archer, a film preservationist and independent filmmaker.

“This is a great moment where we’ve seen another robust and varied flourishing of Black women before and behind the camera and across media in the independent, art, and Hollywood cinema,” Archer said. Their goal is therefore “to see and reevaluate the legacy of Black women performers.”

The festival’s line-up is appreciably wide ranging. Recognition from the Hollywood establishment is the logic underlying the programming. The festival opens with “Carmen Jones,” the 1954 musical starring Dorothy Dandridge in the role that received the first Best Actress Oscar nomination for an African-American performer, and closes with “Monster Ball,” whose female lead, Halle Berry, was the first Black actress to win the Oscar in that category.

Featured are celebrated blacktresses through the decades: Dandridge, Berry, Lena Horne, Josephine Baker, Diana Ross, and Whoopi Goldberg to name only a few. There are also the lesser sung pioneers, such as Nina Mae McKinney (1912-1967), who stars in the first all-sound, all-Black feature film, “Hallelujah,” with the marvelous character name of “Chick.” McKinney was widely celebrated as the first African-American bona fide movie star. She signed a five-year contract with MGM studios, which ended up not bearing much fruit since there were such few roles for which melanated women would even be auditioned. Determined to share her talents, McKinney expatriated to Europe, where, according to her biographer, British writer Stephen Bourne, she performed on the BBC and starred as the wife of an African chief opposite Paul Robeson in “Sanders of the River” (1935), a film set in British colonized Nigeria. (Unbeknownst to the actors, the movie’s script was changed post-production to support an imperial worldview, and Robeson did his best to block its release.)

Reflecting on McKinney’s life and career is particularly important at this time when Black Hollywood is dealing with the controversy surrounding the casting of Black British actors and actresses in roles that some prominent figures in the industry such as Samuel L. Jackson say should have gone to US-born actors. The only Black performer nominated for a 2020 Academy Award in the major categories is native Londoner Cynthia Erivo as Best Actress for her role in “Harriet” as the African-American abolitionist leader Harriet Tubman, a casting decision that drew a great deal of negative comment on social media.

So-called “race films” were movies produced exclusively for African-American audiences, roughly between the years 1915 and 1952. They were financed and produced by mostly white-controlled operations outside the Hollywood establishment. Significant in this era was Oscar Micheaux, the African-American director and producer behind some 44 films who was responsible for launching the careers of Black performers like Robeson who went on to mainstream recognition. Micheaux’s “Within Our Gates” (1920), the oldest surviving feature-length film by a Black director, stars Evelyn Preer as a woman reeling from a broken engagement.

Themes of romantic discord took a turn toward women’s empowerment during the Blaxploitation era of filmmaking in the 1970s, overlaying influences of Black Power and racial uplift themes. Representing this period in the “Black Women” festival are such classics as “Foxy Brown” (1974), starring Pam Grier who fights back against forces of both gender and racial oppression in the seedy underbelly of urban ghettoes.

The “Black Women” festival pays de facto tribute to prominent members of the guild who passed away in 2019 by including their acting or directorial work. Diahann Carroll can be seen in “Claudine” (1974), in her Oscar-nominated role, as can the work of the late John Singleton, “Poetic Justice” (1993), which gave singer Janet Jackson her screen debut.

The line-up’s use of Hollywood as a compass — “The experimental cinema is not strongly represented in this go-round!,” explained Archer — shows up the intersectional gaps in the history of Black women’s cinematic representation and the extent to which those challenges remain. Lesbian representation, namely, is modest, seen most outwardly in “The Watermelon Woman” (1996), director Cheryl Dunye’s comic narrative that infuses, in the words of reviewer B. Ruby Rich, “film history, African-American culture, dyke attitudes, race relations, and the mysteries of lesbian attraction” and in “Set it Off” (1996), with the lesbian character of Cleo, played by Queen Latifah. Off-script, openly bisexual Billie Holiday is afforded a full tribute that collects her film and television appearances.

The experiences of Black trans women is not included in the line-up.

“I cannot think of narrative fiction depictions in this period range,” Archer said.

The future of Black women’s representation on and behind the camera will be determined, as it always had been, by a series of factors: the availability of platforms, the strength of voices, the training of vocations. The Devil, we must remember, is in the details.

BLACK WOMEN: TRAILBLAZING AFRICAN-AMERICAN PERFORMERS & IMAGES, 1920-2001 | Film Forum, 209 W. Houston St. | Jan. 17-Feb. 13 | $15 at filmforum.org