Munich seems an essential operatic tourist destination. The Bavarian State Opera, historically strong, is rocking out under Nikolaus Bachler. As manifest in two astonishing March Carnegie concerts, principal conductor Kirill Petrenko is — welcomely without much hype or projected ego — among today’s most accomplished maestri. Beyond this, Munich offers unbelievably rich and varied museums and architecture, fantastic parks, easy transport (including bicycles), and distinctly LGBTQ neighborhoods and festivals.

The annual opera festival reprises the company’s season highlights and marks the rare major European company performing throughout July, while offering a jumping-off place for the nearby Salzburg and Bayreuth festivals. The grand, central National Theater presides, but the company also uses a striking Art Nouveau structure called the Prinzregenentheatr and — very occasionally — the tiny baroque Cuvilliés-Theater, in which Mozart premiered “Idomeneo” in 1786.

On July 29, Haydn’s musically rich 1782 “Orlando Paladino” filled the Prinzregenentheatr. Never a great dramatist, Haydn achieved relative success here with a beautifully scored “dramma eroicomico” based on Ariosto’s epic of besotted love. Mainstream opera direction in Central Europe frequently involves adding unscripted characters and appending texts, essentially to make the composer and librettist’s work more an extension of the director’s personal mythology. This can yield brilliant results. Or not. It certainly interferes with audiences’ initial introduction to rare fare like “Orlando Paladino.”

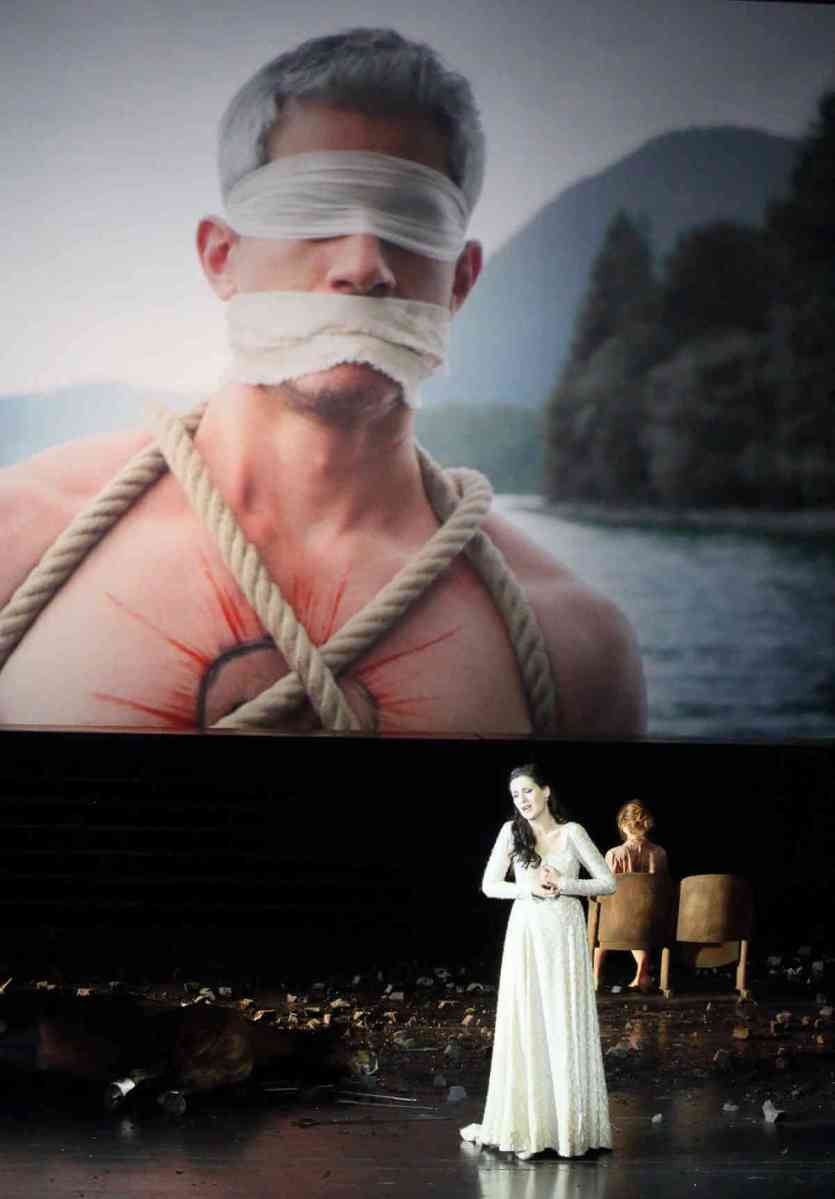

Axel Ranisch, a film director, brought his usual milieu with him, writ large. Not only did the action — largely outdoors in the libretto — take place in an increasingly destroyed art cinema (spiffily designed by Falko Herold) but filmed sequences appeared: a silent entitled “Angelica und Medoro,” and many “behind the scenes” sequences, without exception upstaging and distracting from orchestral or vocal events. Too often, one could sense that the audience was watching, not listening.

The added characters were a middle-aged couple who owned the arthouse, where their daughter doubled as concessions girl and — in the other plot — the sorceress Alcina. Mezzo Tara Erraught had fun with this part but despite hype the voice strikes me as unspecial if large, with the lower end rather commonplace. In the initial, bury-the-overture film, she catches her father (actor Heiko Herz) getting off on pictures of “Rudolfo,” the glamorous star of “Angelica und Medoro,” the impossibly handsome Edwin Crossley-Mercer. A fine, highly intelligent bass-baritone, Crossley-Mercer could star in “Anderson Cooper: The Opera.” Rudolfo, playing Orlando’s rival Rodomonte in the plot, largely — and fluently — stormed and raged. But long video sequences detail his eating a sandwich (way overshadowing the leading lady’s big aria) and being abducted by Heiko, who ties him up and seems to try and coax him into porn with the blindfolded Orlando, all this on a vast rocky shore. In the film, Rudolfo stalks off, but when back in the cinema context, he pairs off with the paunchy, bearded Heiko. Take it from a paunchy, bearded reviewer: this is strictly wish fulfillment on (coincidentally paunchy, bearded) director Ranisch’s part. The opera’s lieto fine (happy ending) merrily explores all the possible pairings of the characters, but the whole staging seemed to be an exploration of Ranisch’s crush on — in a group of singers striking for their good looks — his hunkiest cast member.

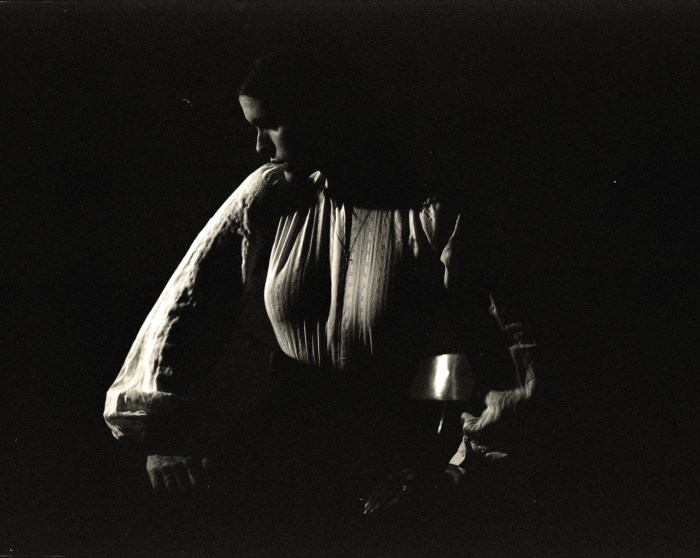

There was much skillfully evoked to enjoy here, but the nominal romantic triangle got rather lost, despite a trio of strong performances from tall, model-figured Adela Zaharia (Angelica), fine Mozart tenor Dovlet Nurgeldiyev (Medoro), and Mathias Vidal (crazed dynamo Orlando). As in Handel’s “Orlando,” the title character has the more dramatic and Medoro the more beautiful music. Vidal’s early baroque roots showed in his lean style and frequent semi-parlando effects. Zaharia, clearly a budding star, has a gorgeous middle and top voice, though it took her two arias to warm up to its full sheen. If she can summon better trills, she’d be a great Constanze.

As the inevitable “second” couple, Elena Sancho-Pereg (Eurilla) showed a monochrome but perfectly apt, agile soprano and grace onstage; high-flying American tenor David Portillo (Pasquale) scored a triumph with the squire’s meta-musical aria evoking different musical instruments and techniques. Joining the dance sextet, star baroque bass Francois Lis (Caronte) offered an incisive cameo. Ivor Bolton’s conducting was sometimes overemphatic — words were tough to hear in the ensembles — but the stylish Muenchner Kammerorchester (with two harpsichords) played with high distinction.

The next night, the main theater staged “From the House of the Dead.” Patrice Chéreau’s Aix staging, seen at the Met in 2009, remains hard to beat for coherent treatment of Janácek’s Dostoevsky-based final opera. The work has strands of a narrative and three big monologues instead of a conventional plot. Alas, director Frank Castorf muddied things maximally, introducing mimed text with subtitles on a huge video screen that severely upstaged and undercut key musical and vocal points. Spanish (!) spoken text prolongedly divided the final two acts.

Castorf’s direction and skilled design team maximized squalor, failing to properly introduce almost any of the characters — admittedly a tough job here — and adducing as many 20th century German iconographic clichés about Russia in its grab-bag way as as von Sternberg’s “The Scarlet Empress.”

But again the musical side was very strong, led by Simone Young with commendable force and clarity of detail. Only some brass smudging suggested an orchestra anxious for vacation in another two days. Veteran Slovak bass Peter Mikulás made Goryanchikov vivid and idiomatic. Of the episodic piece’s three real “leads,” the very best vocalism came from today’s leading Czech tenor, Ales Briscein (Luka). American Charles Workman, a Europe-based tenor who’s a stylistic chameleon and a deft singing actor, found lyricism in Skuratov’s music, but Castorf mistakenly had him channel batshit crazy from the start. Bo Skovhus — made up to cover his autumnal handsomeness in welts — took time to warm up and never matched Peter Mattei’s legato miracles at the Met, but sang strongly, projecting Shishkov’s mania with interpretive power. The Tartar boy Aljeja doubled as a Lulu-does-Papagena eagle figure in a red spangly dress and was pawed by his “mentor,” Goryanchikov. Evgeniya Sotnikova sang him brightly with the usual Russian disregard for Czech phonetics.

In a powerful if often confusingly presented ensemble, we got outstanding work in small bass roles: Peter Lobert as an Orthodox priest mysteriously let loose to work a Soviet gulag, Callum Thorpe as Don Juan in the prisoners’ play (smutted up by Castorf and destroyed by the videography), and Christian Rieger (fetishized in leather Nazi style) as the Commandant.

It was a thrill to have my first-ever Bayreuth performance (August 1) be “Parsifal,” the only work Richard Wagner orchestrated for his theater’s remarkable acoustics. The spectacular orchestral playing under Semyon Bychkov and chorus under Eberhard Friedrich proved unforgettable: the oft-described layering of the choruses in the Grail-uncovering sections is indeed amazing to experience.

Bychkov’s first act created astounding atmosphere; the second less so, in part due to some staging oddnesses. Uwe Eric Laufenberg’s modern-dress production introduced a few too many conflicting ideas and images, though the Iraqi setting and ultimate message of achieving redemption through abjuring war and ideology was well meant. Certainly I’ve never seen a “Parsifal” first act so centered on monastic life; Gisbert Jaekel’s second act set, with a tiled Turkish bath in which the Flowermaidens cavort with Parsifal, was beautiful. But the identities and significance of many extras (a boy, some ominous Western soldiers at one point led by Parsifal) was unclear, and we experienced curious absences and presences. The disembodied Titurel (Tobias Kehrer, outstanding) not only appeared onstage but opened the Grail he claimed he couldn’t; Amfortas — kidnapped? — lingered throughout Act II, seemingly at once present and fantasized; naked choristers showered in Cranach-like bliss in Good Friday rains; unbelievably, Parsifal changed back into fatigues offstage while Kundry confessed her originary transgression; and then she and the redemptive death she sought were nowhere evident in the final scene’s dry ice fadeout. To me, it didn’t add up cogently.

Guenther Groissboeck’s seemingly tireless, non-ranting Gurnemanz took top vocal honors, but Thomas Johannes Mayer made an impassioned strong-voiced Amfortas and Derek Welton — clear and un-gruff — made an exceptional Klingsor. Andreas Schager’s Parsifal was wildly acclaimed — he’s tall, presentable, and offers native German — but I found him rather unimaginative, slightly wobbly, and too often shy of pitch.

Elena Pankratova, less precise of diction, nevertheless sang Kundry with great feeling and a fantastically rich instrument. The Flowermaidens were strong if not transcendent; the Knights (Tansel Akzeybek and Timo Riihonen) made vivid impressions. In the end, Bychkov and his instrumental forces won the most intense applause.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.