Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), a conservative religiously-oriented “public interest” law firm, asked the US Supreme Court on March 27 to strike down state and local laws that forbid licensed counselors from performing conversion therapy on minors. Representing Brian Tingley, a licensed family counselor in the state of Washington who sued to invalidate that state’s ban, ADF contends that such therapy consists of pure speech that enjoys maximum protection against state regulation under the First Amendment’s “free speech” clause. ADF also argues that these laws particularly target counselors who base their counseling practice on their religious views and therefore should enjoy maximum protection under the Free Exercise Clause as well.

ADF’s petition asks the court to reverse a ruling by the San Francisco-based US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which rejected Tingley’s challenge to the Washington law based on the Ninth Circuit’s prior decision in Pickup v. Brown, a 2014 ruling that rejected similar First Amendment arguments aimed at California’s essentially identical conversion therapy ban. In that case, the Ninth Circuit held that the practice of conversion therapy is “professional conduct” that incidentally affects “speech” because the therapy may involve speech in the form of talking between the counselor and their client.

Historically, practitioners of conversion therapy have used a variety of techniques to attempt to alter the sexual orientation or gender identity of clients, but the recent lawsuits attacking laws that ban the practice have all described the therapy (which they do not call “conversion therapy” but instead “reparative therapy” or “sexual orientation change efforts” in an attempt to give it a more affirmative connotation) as purely involving speech. The Pickup court emphasized the traditional role of the state in regulating health care practice, and cited legislative findings about harms caused by the practice of conversion therapy on minors.

More recently, the Atlanta-based 11th Circuit Court of Appeals sharply criticized the Pickup ruling in 2022 in the case of Otto v. City of Boca Raton, which struck down a local ordinance banning conversion therapy for minors, having accepted the argument that pure speech was involved and that the state lacked a compelling interest to forbid its practice on minors.

In the Tingley case, the Ninth Circuit’s three-judge panel held that it was bound to follow the Ninth Circuit precedent of Pickup. ADF sought review by an enlarged panel of the circuit (referred to as “en banc” review, which involves 11 judges in the Ninth Circuit), but their request failed to win the support of a majority of the circuit’s judges, so it was denied, over the dissent of several judges.

A complicating factor is that in 2018, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the court in the case of National Institute of Family & Life Advocates (NIFLA) v. Becerra, criticized the Ninth Circuit’s Pickup decision as having applied, in his view, the wrong standard of review in Pickup. Justice Thomas insisted that “professional speech” enjoys no less protection against government regulation than other forms of speech. However, the Ninth Circuit panel in Tingley’s case stated that the NIFLA ruling was not incompatible with the Ninth Circuit’s ruling in the NIFLA case, distinguishing it on several grounds.

The Ninth Circuit judges who dissented from the denial of en banc review in Tingley’s case argued that the NIFLA ruling by the Supreme Court should control on this issue, despite the differences pointed out in the panel decision.

True to its mission, ADF has also asked the Supreme Court to use Tingley’s case as a vehicle to overrule the court’s 1990 decision in Employment Division v. Smith. ADF and other religious rights advocacy groups have been trying to get the court to overrule Smith for many years. In Smith, Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for a sharply divided Court, ruled that generally applicable laws that incidentally burden an individual’s free exercise of religion are not subject to the strictest level of judicial review, but should be upheld as long as they don’t specifically target religion and satisfy the relatively undemanding rationality standard. That case upheld the refusal of Oregon to pay unemployment benefits to two drug counselors who lost their jobs when they tested positive on their employer’s drug tests, due to the lingering effects of their usage of peyote in a Native American religious ritual. The employees argued that depriving them of the benefits violated their right to practice their religion. Oregon’s unemployment benefit law disqualified people who were discharged for cause, and the Supreme Court held that the employer was entitled to dismiss drug counselors who flunked a drug test, so it was rational for the state to deny unemployment benefits, which are funded through a payroll tax on employers.

The Smith ruling, controversial when it was decided, led Congress and many states to pass religious freedom statutes that allow people to defend against government enforcement actions by citing their religious beliefs. The federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act provides that the strict scrutiny standard applies if the federal government’s enforcement of a federal law substantially burdens an individual’s religious exercise, placing the burden on the government to show that it has a compelling interest in enforcing the law and that there is no less restrictive alternative to achieving that interest. Several members of the Supreme Court have signaled their eagerness, in dissenting or concurring opinions, to overrule Smith and “restore” the prior Supreme Court precedents using the strict scrutiny test whenever a law incidentally burdens religious free exercise. Overruling Smith could empower those with anti-LGBTQ religious views to defy anti-discrimination laws.

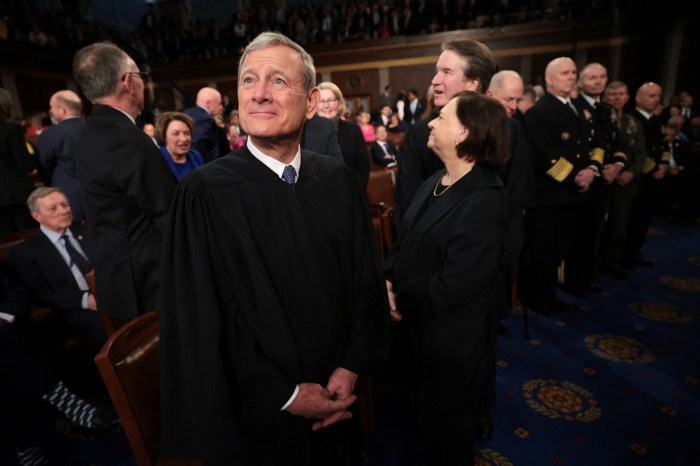

Because of the sharp split between the Ninth and 11th Circuits over the constitutionality of conversion therapy bans, it is likely that there will be at least four votes on the court to grant review in this case, which are all that are required (although it ultimately takes five votes to decide a case). In 2021, it appeared possible that the court would overrule Smith in Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, the case involving refusal of Catholic Social Services to comply with the city’s requirement that it not discriminate based on sexual orientation in operating a foster care certification process by contract with the city. However, Chief Justice John Roberts engineered a decision for CSS without overruling Smith, to the expressed disappointment of several concurring judges joining an opinion by Justice Neil Gorsuch, who protested that the court had granted review in that case expressly to reconsider its holding in Smith.

If ADF’s petition is granted, the case will not be heard until the 2023-24 term of the court, which begins in October.