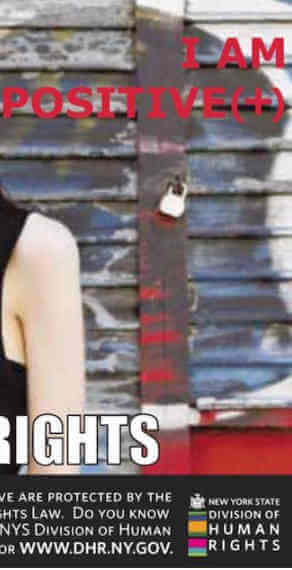

New York Court of Claims Judge Thomas H. Scuccimarra has decided that the State of New York should pay Avril Nolan $125,000 for using her photo in an HIV discrimination ad campaign without a disclaimer that the person in the picture was a “model.”

The November 8 ruling came after the Appellate Division’s Brooklyn-based Second Department ruled in January that use of the photo in print and online advertisements, in which the statement “I AM POSITIVE (+)” appeared next to the photo, was defamatory as a matter of law, and sent the case back to the Court of Claims for a determination of damages. Nolan is not HIV-positive.

The outcome of this case says much about the way in which courts, in rulings ostensibly taking on the stigma surrounding HIV, may well be contributing to that stigma.

According to Scuccimarra’s opinion, photographer Jena Cumbo took the photo of Nolan for a 2011 feature in Soma magazine that briefly profiled those pictured regarding their musical interests. Cumbo did not have Nolan sign a release and, without asking her permission, sold the photograph to Getty Images, which sells news and stock photos to publications and companies for use in stories and campaigns.

The State Division of Human Rights, planning an ad campaign to educate the public that it is illegal to discriminate against people based on their HIV status, chose not to locate people living with HIV willing to be photographed but instead purchased the right to use Nolan’s photo from Getty. Getty mistakenly represented that Nolan had signed a general release.

The hearing the Court of Claims held regarding damages owed to Nolan focused on how she heard about the ad, her subsequent contacts with AM New York, which ran the ad, and with the Division of Human Rights, and the impact its publication had on her life.

Nolan, an Irish immigrant who worked for a fashion industry PR company, learned about the ad in April 2013, when she arrived at work and saw a Facebook friend’s post on her page asking whether she was in that morning’s AM New York. The acquaintance later sent her a private message with an image of the ad.

Nolan testified that when she saw the image she “was completely shocked” and “confused,” that when she saw the “words, ‘I am positive,’ beside my face, I was devastated.” She added that she felt her “world was just falling down around her,” especially because AM New York was a “big target” for two of her clients.

Nolan got a copy of the newspaper and, she testified, felt “sick to the bottom of my stomach.” She feared for her career in her office’s intensely competitive atmosphere. On advice of a friend, she told her bosses that morning, showing them the newspaper. She testified that she was “very, very emotional” and “couldn’t stop crying” as she spoke to them. Although her bosses expressed shock, she says that they “calmly went into crisis PR mode,” assessing how it could have happened and whether any clients could have seen it. They did not fire her, as she had feared.

When Nolan contacted Cumbo, the photographer, Cumbo in turn reached out to AM New York, Getty, and the Division of Human Rights. A DHR representative later informed Nolan, “After speaking with a Getty representative we have been told we are not liable. We are acting in good faith to remove the image based on the model’s request.”

The DHR staffer asked Nolan to send them an email stating she would not hold DHR liable and said, “We need the email sooner rather than later as a number of publications are on deadline and are scheduled to move forward with the campaign with Ms. Nolan’s image.”

Nolan responded, “Discussing this matter to get further advice but please remove my image from the advertisements. This has already caused enough problems and embarrassment.”

Nolan heard nothing more from DHR and, though she testified she suffered considerable emotional distress, her worry about the matter subsided — even if it took her “a couple years” to rebuild her confidence. During the discovery process for this lawsuit, however, she learned that the ad had been used in four print publications and three online publications, which triggered again her concerns about how many people might have seen it. Despite a few incidents, the issue generally did not come up or have any substantial effect on her work.

Asked during the hearing what this “association with HIV” meant to her, she testified that while unfortunate, there is “so much stigma around it… It’s not like I was in an ad for cancer treatment” where sympathy would be elicited. “There’s a lot of negativity around it,” she testified, “and there’s a lot of associations that people jump to incorrectly about your lifestyle. People think you’re easy, or you’re promiscuous. There’s a lot of just questions around your sexual behavior and your sexual activity. It makes people really think about something so personal to you. It also brings up drug use and just all of these things that I did not want to be associated with and was very embarrassed to be associated with. This goes much deeper, and it really calls into question you as a person and your lifestyle.”

Still, Judge Scuccimarra noted in his decision, Nolan “did not lose her job nor did she miss any time from work when the advertisement came out. She did not lose any friends. No one other than the acquaintance who first told her about the ad, her Pilates teacher, and the outside producer [from an ad shoot] ever informed her that they recognized her as the person depicted in the ad. Indeed, when [she] conducted an online search that day she was unable to see a copy of the advertisement.”

The judge reviewed testimony by several witnesses about the psychological impact of the ad on Nolan, leading to the conclusion that she had been tense and nervous in the period following the publication, but the effects dissipated with time and she eventually returned to normal.

As the Appellate Division ruled in January, for the purposes of defamation liability falsely labeling somebody as HIV-positive — despite changing public attitudes about HIV/ AIDS — fell into the “loathsome disease” category, in which some injury is presumed and the plaintiff is entitled to damages without any requirement to show financial harm. Courts do have discretion, however, regarding the amount awarded and will make comparisons to comparable cases.

Scuccimarra credited “Nolan’s assessment of a culture of competition at her job, and in the public relations field generally, that left her particularly vulnerable as a young woman to the extreme anxiety and distress she suffered upon publication of the defamatory material. The court also credits the increased anxiety she experienced when imagining how many people could potentially see the ad and make judgments about her that she feared… This event credibly triggered a setback for her in her confidence and outward demeanor, but she appears to have come out of the experience.”

The judge decided that based on the “humiliation, mental suffering, anxiety, and loss of confidence suffered by this young woman at the beginning of her career, and at the beginning of her growing independence, the vast extent to which the defamatory material was circulated — albeit for the laudatory purpose of getting public service information out to as many people as possible — and all the circumstances herein,” a reasonable compensation would be $125,000. Nolan was also awarded interest on that amount from June 18, 2015, the date when Scuccimarra had first ruled in her favor prior to the state’s appeal.

Nolan was represented by attorney Erin E. Lloyd of the firm Lloyd Patel LLP. Assistant Attorney General Cheryl M. Rameau represented the State of New York.