On September 20, 2011, Rob Smith, then 29, was among the crowd at the Stonewall Inn that joined the advocacy group Servicemembers Legal Defense Network in celebrating the official end date for the military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy.

“It feels amazing,” the former infantryman told Gay City News that day. “I feel relieved. This is a signal to see we can fight and we can win.”

Two and a half years later, Smith comes forward with his memoir of his time in the military. “Closets, Combat + Coming Out: Coming of Age as a Gay Man in the ‘Don’t Ask Don’t Tell’ Army” is a mouthful of a title. That is, perhaps, because Smith’s ambitious book is about a lot of things.

It is not primarily a story about the military’s former anti-gay policy, though we do learn about the everyday terror and soul-sapping despair it caused in soldiers — especially against the backdrop of brutal homophobic crimes the policy, on occasion, enabled.

Nor is Smith’s memoir first and foremost a coming out story — though he entered the army at 17 sexually naïve and secretive, having “messed around” with two guys but never kissed one, and returned to civilian life four years later knowing he was gay and that he couldn’t pretend otherwise, even if he wanted to.

“Closets, Combat + Coming Out” can best be described as a coming of age story. But not just for a closeted soldier in a military that was officially homophobic. Also for a young African-American man who was a straight-A student in high school but lacked the financial wherewithal to get to college and so was waiting tables part-time at Denny’s before the Army held out a lifeline. And for an overweight, out of shape kid who chose the infantry because that’s “where the real men go… where they do the real shooting.”

And, finally, for an ambitious would-be journalist who judged military service his best route to an education and became embroiled in a post-9/11 foreign misadventure where he wouldn’t be the only soldier to say, “I wasn’t sure what we were doing here.”

In telling that coming of age story, Smith sheds light on the lack of opportunity facing too many talented young people in America today, how economic disparities largely determine who it is that defends this country and who has chances to do other more lucrative, less dangerous things, how racism continues to infect a military that was desegregated 60 years before it allowed open gay and lesbian service, and how the brutality and chaos of war make it possible — perhaps at some point, inevitable — to look at a “lifeless body and feel nothing.”

Many successful memoirs involve an heroic triumph over harrowing odds — often odds created by the narrator’s own character flaws, such as drug addiction or criminal acts, or by the dire hand dealt them, whether poverty or family dysfunction. It is to Smith’s considerable credit that he avoids the pitfalls of sensationalizing his story. In the process, he has created a highly relatable account of a young man overcoming considerable odds and coming out whole on the other side.

Rob Smith drew up in a predominately black section of Akron, Ohio, “a dirty, dingy place” where “all the failed hopes and ambitions of its citizens were somehow released into the air and absorbed into everything around it, draining the sky of its color and the sun of its brightness.” His parents split up when he was very young, and he endured years living with a physically abusive stepfather, until the man disappeared and his mother largely left him in the care of his maternal grandmother.

Smith “didn’t get along” with his grandmother, voices considerable anger at his mother for her preoccupation with a series of failed marriages that kept his growing up well in the background, and reports that his relationship with his father was distant. Still, aside from his stepfather, Smith never faced outright rejection, and both his mother and father, each in their own way, seem to have instinctive insight into their son. On at least one occasion, Smith is pleasantly surprised by what he gets back.

Though Akron is a majority white city, the neighborhood where Smith grew up is a part of America that apparently remains segregated half a century after the peak of the Civil Rights Movement. “I didn't have much contact with white people,” he writes. “They were people on the shows that I watched, people reporting the news, but not people I'd had any interaction with whatsoever in my daily life.”

Basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia proved a shock in that regard. In a 124-person company, Smith was one of only three black soldiers. Throughout his time in the infantry, he took note of the “casual racism” — in the nickname borrowed from a popular film that attached itself to him, in the resentment from a fellow basic training recruit who accused him of being a “showoff” when Smith finally began to master some of the Army’s physical demands, and in the anger of a fellow Iraq War fighter who told him, “You're supposed to be here because you love your fucking country not because you want money for fuckin' college.”

If his race marked him as an outsider to some of his fellow soldiers, Smith was unable to turn it to his advantage. In the book’s chilling opening scene, when moments after first reporting for duty, a drill sergeant is all over him, screaming, “What are you, a fucking faggot?,” Smith fantasizes about using his black skin against his tormentor. “Maybe I could get his old white ass to think I was some thug from the projects of Detroit instead of a solidly lower-middle class geek from Ohio,” he writes, but already on page 11 we know this is not who we are reading about.

Smith was an unlikely Army recruit. Shortly after his day one hazing by the drill sergeant, he is on his first run, his breath “short and staggered,” feeling as if he would hyperventilate. After being humiliated as a “fucking faggot” moments before, Smith could feel his stock falling further in the eyes of his fellow recruits: “The emotions ranged from pity to anger to disgust. I could see their opinions of me forming in their eyes. It looked like I was to be here what I was in high school — a loser, the fat kid.”

Smith makes no bones about why he joined. “I had come to Fort Benning, and the Army on a whim,” hoping to earn a college degree “on the Army’s dime.” It didn’t hurt that the recruiter first sent to his Akron home was a blonde, blue-eyed “Adonis.” Smith writes, “I knew that I just wanted to be with him.”

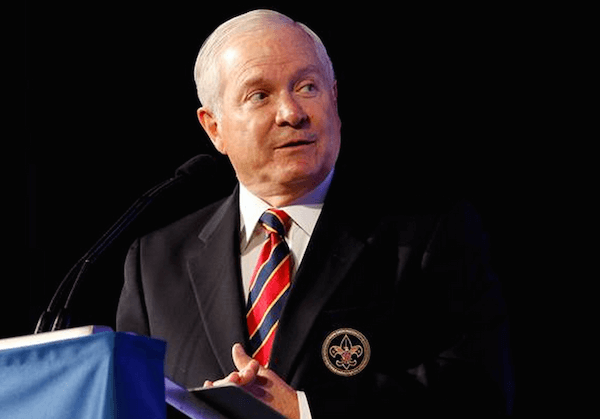

Author and Iraq War veteran Rob Smith. | OMAR C PHOTOGRAPHY

The most remarkable part of Smith’s story is the turnaround he achieves during his six months in basic training. It must certainly have been painful for him to write about the daily failures he suffered in his early days — in the field and in the catcalls from his fellow soldiers.

“The words were all the same, some unimaginative version of ‘weak,’ ‘faggot,’ and ‘pussy’ strung together by ‘fuck,’ ‘shit,’ and ‘punk,’” he writes. “The usual. The situation was taking its toll on me, and I started to feel like a different person. Before, I never felt the way they described me, but now I couldn't remove the words from my head when I thought of myself, or looked at myself in the mirror.” He would spend long stretches of time alone, writing over and over in a journal, “I hate it here.”

But just as another soldier’s crisis seems to bring his own situation to a head, Smith realizes, “I don't have anywhere else to go.” And in that recognition, his “crushing fear… was replaced by a desire to do better.” He survives basic training, and in some tasks even excels.

Surmounting his physical demons — the abs he develops even win praise from his drill sergeant nemesis — doesn’t mean, by any stretch, that his being gay is no longer an issue. On the way to his post-basic training assignment at Fort Carson, Colorado, he reads about the Fort Campbell, Kentucky murder of Private First Class Barry Winchell, targeted as a “faggot” for dating a local transgender woman. It was apparently only then that he realized the full meaning of the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy. “I ended the day very afraid,” he recalls.

An ugly incident on his 18th birthday reinforces Smith’s instinctive caution, but this time, unlike his preceding six months of hurt in basic training, he uses his time alone to find out about himself and what the world holds for him.

When Smith entered the army, “No one was expecting any wars anytime soon.” That all changed, of course, on 9/11, and by the time he left for Iraq, he seems to be a new man. He’s rightly suspicious of the mission and honest and self-confident enough to talk to a straight Army buddy about being gay — and also about being afraid to go to war. He is clear-eyed in seeing the insanity of his squad sergeant’s behavior and, in a climactic scene of warfare, confronts him head on.

And then suddenly — like so much of the random chaos that surrounds him — his time is up and he goes home, having survived Iraq with his body and humanity intact. Smith is no longer the naïve 17-year-old he was but only part of the way down the road to being the man he is today. Seven years later, as Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell repeal appears perilously close to failing in the US Senate in late 2010, he is among 13 activists who chain themselves to the White House gate to demand action. He has become a gay activist.

The greatest strength of “Closets, Combat + Coming Out” comes from Smith’s confidence in the power of his story. There is no hyperbole but nor is there any prettying up of the painful ridicule, doubt, and self-loathing he went through just as he was coming of age. This is the story of a decent, even inspiring young man, and its lessons will resonate with many for whom the specifics of life may be very different.

CLOSETS, COMBAT + COMING OUT: Coming of Age as a Gay Man in the “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” Army | By Rob Smith | Blue Beacon Books/ Regal Crest | $15.95 | 208 pages