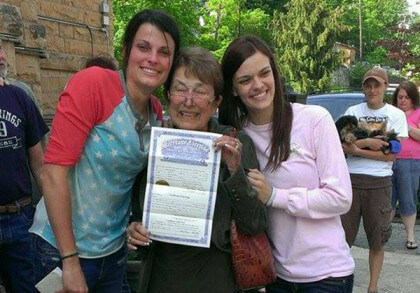

Plaintiffs Lisa Chickadonz and Christine Tanner. | OREGON UNITED FOR MARRIAGE.ORG

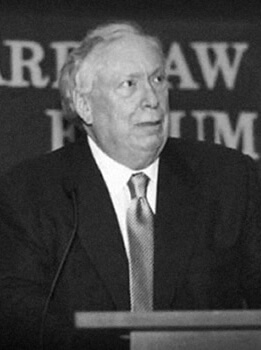

US District Judge Michael McShane’s permanent injunction against Oregon’s statutory and constitutional ban on same-sex marriage and its recognition was based on his finding that the state has no rational basis for that policy.

McShane decreed that his May 19 ruling “be effective immediately,” and couples began getting married the same afternoon.

Since neither the state nor Multnomah County, the other defendant in the lawsuit, defended the existing ban or plans an appeal and there is only a remote chance of the ruling otherwise being challenged in a higher court, Oregon becomes the 18th marriage equality state.

Planning no appeal, state welcomes ruling; licenses issued to same-sex couples

The National Organization for Marriage (NOM), an organization formed specifically to oppose same-sex marriage, had filed a last-minute motion to intervene as a defendant in the case shortly before the court’s scheduled hearing last month, but McShane denied it on May 13.

NOM then filed an appeal from his ruling with the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and sought an “emergency stay” of the district court proceedings, hoping to block the court from issuing its opinion. Hours before McShane ruled, the Ninth Circuit denied that motion. NOM’s appeal of the judge’s ruling on its motion to intervene remains pending, a remaining issue that could –– but probably won’t –– interfere with the ability of same-sex couples to wed now in Oregon.

The unlikelihood of such a scenario is buffered by the Supreme Court’s ruling last year that the proponents of California’s Proposition 8 had no standing to appeal the 2010 district court ruling that struck down that voter initiative from two years earlier. McShane predicated his denial of the NOM motion on that conclusion.

The lawsuit was brought by four plaintiff couples –– two represented by Portland attorneys Lake Perriguey and Lea Ann Easton and two by the American Civil Liberties Union and its Oregon affiliate.

McShane, an out gay appointee of President Barack Obama who began serving on the district court last year, included some deeply personal reflections in his opinion.

“Generations of Americans, my own included, were raised in a world in which homosexuality was believed to be a moral perversion, a mental disorder, or a mortal sin,” he wrote. “I remember that one of the more popular playground games of my childhood was called ‘smear the queer’ and it was played with great zeal and without a moment’s thought to today’s political correctness. On a darker level, that same worldview led to an environment of cruelty, violence, and self-loathing. It was but 1986 when the United States Supreme Court justified, on the basis of a ‘millennia of moral teaching,’ the imprisonment of gay men and lesbian women who engaged in consensual sexual acts. Even today I am reminded of the legacy that we have bequeathed today’s generation when my son looks dismissively at the sweater I bought him for Christmas and, with a roll of his eyes, says ‘Dad… that is so gay.’”

Later in the opinion, he conceded, “My decision will not be the final word on this subject, but on this issue of marriage I am struck more by our similarities than our differences. I believe that if we can look for a moment past gender and sexuality, we can see in these plaintiffs nothing more or less than our own families. Families who we would expect our Constitution to protect, if not exalt, in equal measure. With discernment we see not shadows lurking in closets or the stereotypes of what was once believed; rather, we see families committed to the common purpose of love, devotion, and service to the greater community.”

He continued, “Where will all this lead? I know that many suggest we are going down a slippery slope that will have no moral boundaries. To those who truly harbor such fears, I can only say this: Let us look less to the sky to see what might fall; rather, let us look to each other… and rise.”

McShane’s opinion took a narrowly focused equal protection approach to the case. Significantly, he rejected the plaintiffs’ argument that denying marriage to same-sex couples was a form of sex discrimination that would require the court to apply heightened scrutiny, under which the existing ban would be presumed unconstitutional and the state would have to affirmatively make the case for its necessity.

Instead, McShane insisted, this case was about sexual orientation discrimination. While acknowledging that a Ninth Circuit panel, in an unrelated case in January, ruled that sexual orientation discrimination claims should invoke heightened scrutiny, he pointed out that the ruling was not yet “final” and therefore not a binding precedent.

That did not matter to the outcome of this case, McShane found, because “the state’s marriage laws cannot withstand even the most relaxed level of scrutiny.” Both the state and Multnomah County joined the plaintiffs in arguing that the law was unconstitutional, so the judge relied on amicus briefs and arguments made in other marriage equality cases to consider whether there was any rational justification for Oregon to refuse to allow same-sex couples to marry.

Plaintiffs Ben West and Paul Rummel. | OREGON UNITED FOR MARRIAGE.ORG

Unlike some of the other states in which same-sex marriage bans were struck down in federal court in recent months, Oregon already provided same-sex couples with nearly all of the state law rights of marriage through a domestic partnership statute adopted seven years ago. And after last summer’s ruling in Edie Windsor’s challenge to the Defense of Marriage Act, Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum issued a formal opinion that state agencies should recognize legal same-sex marriages from other states. As a result, McShane concluded, it was difficult to hypothesize how any legitimate state interest was being advanced by denying marriage to same-sex couples.

The judge focused on two types of arguments generally advanced by opponents of same-sex marriage. One is that the states have a right to maintain longstanding traditions deeply rooted in history and the belief systems of many citizens.

“Such beliefs likely informed the votes of many who favored Measure 36,” the 2004 constitutional amendment question approved by voters in 2004, McShane wrote. “However, as expressed merely a year before Measure 36's passage” in the Supreme Court’s Texas sodomy decision, “moral disapproval of a group cannot be a legitimate governmental interest under the Equal Protection Clause because legal classifications must not be drawn for the purpose of disadvantaging the group burdened by the law.” The high court reiterated its conclusion on that point in last year’s DOMA ruling.

Emphasizing that the debate is about civil marriage, not religious marriage, McShane wrote, “Overturning the discriminatory marriage laws will not upset Oregonians’ religious beliefs and freedoms.”

The other type of arguments McShane addressed were those about “protecting children and encouraging stable families.” Here he echoed the findings of a long string of federal marriage equality rulings since Utah’s in December.

“Although protecting children and promoting stable families is certainly a legitimate governmental interest,” he wrote, “the state’s marriage laws do not advance this interest — they harm it.” He noted that Oregon’s domestic partnership law articulated “a strong interest in promoting stable and lasting families, including the families of same-sex couples and their children,” evidence that the state’s own policymakers saw no state interest in depriving same-sex couples and their children of the same legal rights provided to different-sex couples and their children. “With this finding,” McShane wrote, “the legislature acknowledged that our communities depend on, and are strengthened by, strong, stable families of all types whether headed by gay, lesbian, or straight couples.”

Withholding the “full rights, benefits, and responsibilities of marriage” forces the state “to burden, demean, and harm gay and lesbian couples and their families so long as its current marriage laws stand,” the judge found, concluding that violates the spirit of last year’s Supreme Court DOMA decision. “Creating second-tier families does not advance the state’s strong interest in promoting and protecting all families,” he wrote.

McShane specifically rejected the contention that “any governmental interest in responsible procreation” would be “advanced by denying marriage to gay and lesbian couples” because “there is no logical nexus between the interest and the exclusion. Opposite-gender couples will continue to choose to have children responsibly or not, and those considerations are not impacted in any way by whether same-gender couples are allowed to marry.”

Rejecting the customary justifications for banning same-sex marriage, McShane concluded that “expanding the embrace of civil marriage to gay and lesbian couples will not burden any legitimate state interest. The attractiveness of marriage to opposite-gender couples is not derived from its inaccessibility to same-gender couples. The well-being of Oregon’s children is not enhanced by destabilizing and limiting the rights and resources available to gay and lesbian families… No legitimate state purpose justifies the preclusion of gay and lesbian couples from civil marriage.”

McShane did not address an alternative argument cited by other federal judges recently –– that the Supreme Court’s frequent mention of the right to marry as a fundamental right under the Due Process Clause justifies the use of heightened or even strict scrutiny (the most searching level of judicial review) in reviewing same-sex marriage prohibitions.

The Ninth Circuit is facing the appeal of another marriage equality ruling –– last week’s in Idaho. Theoretically, it could issue a stay of the Oregon order on its own motion, but that is unlikely given that no defendant is seeking appeal and the state is happily complying with McShane’s order.

McShane is the second gay judge –– after District Judge Vaughn Walker, in the Proposition 8 litigation –– to issue a marriage equality ruling. In that case, the voter initiative’s proponents unsuccessfully sought to use his sexuality to have the ruling vacated, and NOM’s current appeal to the Ninth Circuit argues that as a partnered gay man raising a child, McShane should have recused himself. It’s unlikely the Ninth Circuit would credit that argument.