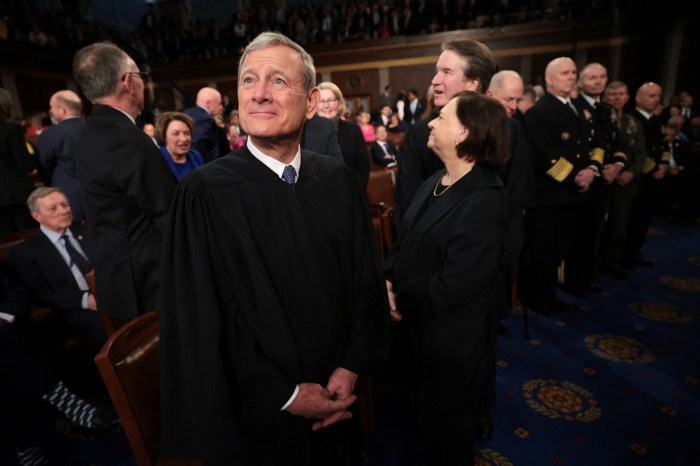

Sam Oglesby, USAID/ State Department officer, in An Loc, South Vietnam in November 1967, standing before a display of local election results, one of the American programs to promote democracy during the war there. | COURTESY: SAM OGLESBY

In today’s post, I received a letter from the US Department of State. Emblazoned on the envelope in bold letters so that no eyeglasses were needed to read it was: AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY EMPLOYER. Unfortunately, this has not always been the case.

In 1968, I was terminated from my job as a Foreign Service officer without being told why. Years later, I learned it was because I was gay. In my teens and 20s, I had studied and worked with one goal in mind — to become a foreign service diplomat following in the footsteps of my father whom I greatly admired. Achieving my goal, I was sent to Vietnam where I worked in perilous combat conditions, proving my mettle to my colleagues and superiors who recommended me for a promotion. Then suddenly I was dismissed. This termination nearly destroyed me, but I pulled my life together and moved on.

Earlier this year, more than 40 years after my dismissal, prompted by the need for closure and with a sense that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton would give my case a fair hearing, I wrote to the secretary and here is the reply I got today:

Dear Mr. Oglesby,

Let me thank you for reaching out to us about your concerns. We take the issue of fairness very seriously, and today’s State Department has strict policies prohibiting discrimination based on an employee’s sexual orientation.

In looking into the issues you raised, we learned that the Department’s employment records from the 1960’s HAVE BEEN DESTROYED, IN ACCORDANCE WITH FEDERAL GUIDELINES. This means we cannot review personnel actions from the time when you worked with the Department. I know this must be disappointing news, and I hope that if you have further concerns that you feel free to reach out to me again.

Sincerely,

Director General of the Foreign Service and Director of Human Resources

Here is my story:

It was 1968, and the war in Vietnam had escalated to a ferocious crest of destruction. As a Foreign Service officer embedded with the American military, I was part of a “nation-building” team that had been dispatched to survey the damage we had wrought and recommend ways to “win back the hearts and minds” of the farmers whose village we had just obliterated.

My translator and I walked up to an old man standing in front of what had been a house, now a heap of scorched bamboo. When we asked him how we might provide help and what did he need, he stared at us in dazed silence before pointing to the carcass of a dead buffalo in a nearby rice paddy.

“My buffalo is dead and I need a new one,” he said. “I can’t survive without this animal. She plows our fields, pulls our cart to market, and provides us with fuel.” My translator and I looked at each other and stammered an apology, unable to help.

Later that evening, after I had flown back to base camp and was unwinding at the Army officers’ club during happy hour, I told my GI buddies about my afternoon visit to the village. When I mentioned the dead buffalo and the old farmer, they fell silent. As I was speaking, somebody started passing a hat along the bar, and before I knew it, I was handed a fistful of cash, nearly $500.

The next morning, I helicoptered back to the village and presented the old farmer with the previous night’s collection. Weeks later, I heard that he had acquired another animal and was rebuilding his house.

An Army buddy of mine, a fellow American I had nicknamed Flaps because of his protruding ears, accompanied me to the village and took a photo of the farmer and his new buffalo. Later, Flaps thumbtacked the picture to the bulletin board at the officers’ club. The GIs nicknamed the buffalo Big Bertha, and she became the club mascot.

Sometime later, I heard that the village was hit again. Somehow, I didn’t want to know what happened to Bertha or her owner. As time passed, both the war and my personal life nose-dived into crisis. Communist forces launched the Tet Offensive, crippling South Vietnamese bases; I broke off my engagement to a beautiful French-Vietnamese woman and told my buddy Flaps that I thought I was gay. Flaps told me my sexuality had been an open secret for months. He drove me to the airport for my flight back to the States, and we promised to stay in touch.

I reached the nation’s capital the day after the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and found myself in another war zone, with buildings aflame and helicopters hovering in the sky. Still jet-lagged and traumatized by the war I found in my hometown, I proceeded to headquarters for “de-briefing” and what I assumed would be reassignment.

According to my performance reports and commendations, I had served with valor and diligence, “beyond the call of duty.” I had worked for nearly a year in a rubber plantation area sprayed with the toxic defoliant Agent Orange. As I headed down the polished corridor to the State Department’s personnel office, I assumed I would be congratulated on my outstanding service, promoted, and offered another challenging assignment.

The interview lasted less than a minute, during which time I was sacked, not lauded. The woman behind the desk informed me that my service had been terminated. Shocked, I asked why I had been fired. Without establishing eye contact, she mumbled, “I don’t know the reason,” and motioned me to the door. The career I had worked so hard for was over in a flash. What had I done?

After my termination, I had a nervous breakdown. But over time, I regained my footing. In fact, I found another job, excelled professionally as a senior United Nations officer, and built a loving relationship with a life partner. Vietnam and my unexplained discharge disappeared down the memory hole — until one evening 42 years later, when I learned the reason I had been fired.

That night, I was celebrating my 71st birthday in Mr. Smith’s, a bar in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington. I was surrounded by friends and overcome with the feeling that life was good.

As I lifted my glass to join in a celebratory toast, I felt a hand on my shoulder and turned to see the smiling face of my old buddy Flaps. We had seen each other off and on over the years. He gave me a hug and in a few words that indicated the extent of Washington’s Beltway grapevine, whispered, “That was a real bummer, your getting fired because you were gay.”

It turned out that a fellow Foreign Service officer, whom I knew from Vietnam, had seen my file and spilled the beans; later it was confirmed to me. My firing was based not on performance but discrimination. With an incredible sense of relief, I realized that I had done nothing wrong.

But now as I re-read the State Department’s letter to me, I am overcome by a sense of disappointment and bitterness. I have become a non-person. My files have disappeared down a memory hole, conveniently absolving my former employer of any wrongdoing, obviating their responsibility to tender to me an apology for an action that nearly ruined my life.

Now that Big Brother has destroyed my files, I am learning the full meaning of the word STOICISM.

Sam Oglesby is a New York-based writer, whose fourth book, “Wordswarm,” was just published.